Hydrogen sulfide has a bad reputation, and deservedly so: not only does the gas smell of rotten eggs, but it is also so toxic that in large quantities it can cause respiratory failure and even death1. But over the last 20 years, biologists have learned that the gas also helps keep the circulatory system functioning properly. Now physiologist Ingrid Fleming and her collaborators speculate that people with atherosclerosis might actually benefit from taking an oral supplement that generates hydrogen sulfide inside their bodies.

Cardiovascular disease, including atherosclerosis, is the main cause of death worldwide and has been a health problem for millennia. Studies of ancient mummies suggest that atherosclerosis was a common problem for the social elite of Egypt even 3,500 years ago. As such, new treatments for the condition are urgently required.

Researchers already knew that an enzyme—cystathionine-gamma-lyase (CSE)—in cells lining the body’s blood vessels naturally generate small quantities of hydrogen sulfide. They also suspected from earlier studies that this hydrogen sulfide helps fight the build-up of plaque and narrowing of arteries associated with atherosclerosis. But exactly how CSE is activated in the body (and how the hydrogen sulfide it generates helps combat circulatory problems) has been unclear.

Fleming, who is at Goethe University Frankfurt in Germany, and her colleagues discovered that the degree of CSE activation in the mouse circulatory system is determined by the rate of blood flow through vessels2. At places where blood flow is reduced, such as branching points in arteries, for instance, CSE is more active. The same applies to cells taken from the walls of human blood vessels and subjected to stresses mimicking those that occur when blood flows over the cells.

The researchers found an explanation for this pattern. At spots where blood flow rate drops and there is a risk of cellular debris accumulating and clogging the vessel, the body creates a more effective ‘non-stick’ surface on the blood vessel walls. CSE generates hydrogen sulfide at these junctures, which ultimately reduces the production of a molecule called E-selectin, a so-called ‘adhesion molecule’ that helps certain white blood cells will stick to vessel walls.

The finding, published in the January issue of the journal Circulation, offers solid and direct evidence that hydrogen sulfide generated by cells lining the body’s blood vessels can protect against atherosclerosis, says Suowen Xu, a pharmacologist at the University of Rochester, New York, who was not involved in the work.

Inflammatory twist

It turns out that other factors besides blood flow can influence CSE and hydrogen sulfide levels, however.

This was evident in the next part of the experiment, when Fleming and her colleagues tied off some branches of the carotid artery in mice to perturb blood flow and mimic the common pattern of arterial clogging seen in people with atherosclerosis. Over the course of three weeks, the team recorded an increase in CSE activity in the manipulated blood vessels. But, to their surprise, there was no uptick in the amount of hydrogen sulfide generated.

The same pattern applied in humans. Atherosclerotic plaques that were surgically extracted from the arteries of people with the condition as part of their treatment showed more CSE activity—but the circulating levels of hydrogen sulphide in these people were lower than expected.

The team soon discovered the reason why. “We found that CSE activity is particularly sensitive to inflammation,” Fleming says.

The narrowing of the artery had induced tissue inflammation, and the researchers realized that a protein associated with the inflammation—interleukin-1β—was blocking the ability of CSE to generate hydrogen sulfide. That’s an important finding, because atherosclerosis is thought to be an inflammatory disease.

Drug fix?

Fleming and her colleagues wondered whether they could artificially boost the amount of hydrogen sulfide in the partially clogged blood vessels in the mice using an ingestible drug that generates the gas once swallowed.

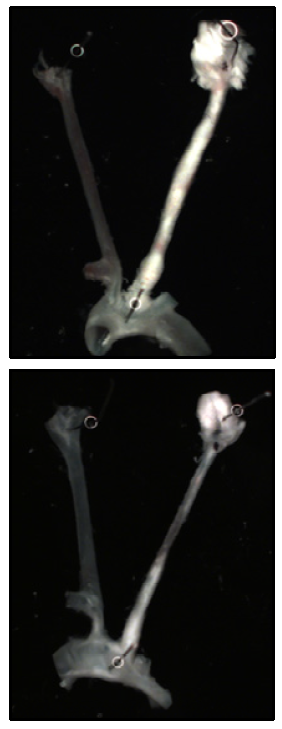

Twenty-one days into the experiment, more atherosclerosis is visible in the arteries mice in the control group (top) compared with those given SG1002 (bottom).

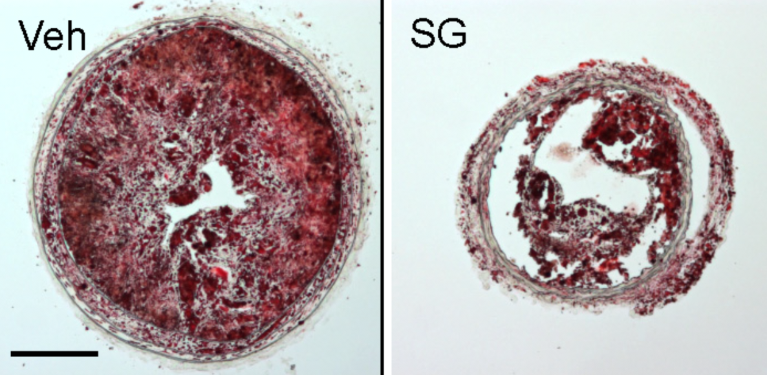

To test the idea, they used a strain of mice that had been bred to lack the ability to generate CSE and that were also prone to developing symptoms of atherosclerosis. When these mice had some carotid artery branches tied off to mimic arterial clogging, plaque deposits built up. But there was significantly less build-up of plaque if the drinking water that the mice received before and after the artery surgery was dosed with a drug—SG1002—that slowly generates hydrogen sulfide when ingested.

“The effect exceeded our expectations,” says Fleming, although she cautions that more work must be done to show that SG1002 can slow down plaque accumulation over the long term.

Matthias Barton, a cardiologist at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, is particularly impressed by the fact that the researchers studied both mouse and human tissues. “This is the first paper to look at human tissues from patients with atherosclerosis,” he says. “It takes the study to a completely new level.”

Fleming says that SG1002 may have the potential to help people with atherosclerosis. “We actually chose to use this compound because it completed phase 1 clinical trials, and a phase 2 trial is running to assess its safety in heart failure patients,” she says.

John Wallace, a physiologist and pharmacologist at the University of Calgary, has founded a company to develop hydrogen-sulfide-releasing, anti-inflammatory drugs. He says the drugs are currently undergoing phase 2 clinical trials for conditions such as arthritis3, with promising results. Wallace says the new study, with its emphasis on the role inflammation plays in hydrogen sulfide activity, may in principle help explain why the drugs he is helping develop are performing so well. Not only do they provide the body with a new source of hydrogen sulfide, but they also tackle the inflammation that blocks the body’s natural hydrogen-sulfide-generating potential.

Barton speculates that some people already benefit from consuming foods with the potential to generate hydrogen sulfide in the body. He says that the garlic at the core of Mediterranean cooking is rich in sulfur. It’s still a mystery why people who eat a Mediterranean diet have good cardiovascular health. “People say it’s because of the olive oil, the legumes, the fresh vegetables,” he says. “But it may be that garlic is a missing link to understanding why this diet is so healthy.”