Abstract

Genetic testing for congenital or early-onset hearing loss patients has become a common diagnostic option in many countries. On the other hand, there are few late-onset hearing loss patients receiving genetic testing, as late-onset hearing loss is believed to be a complex disorder and the diagnostic rate for genetic testing in late-onset patients is lower than that for the congenital cases. To date, the etiology of late-onset hearing loss is largely unknown. In the present study, we recruited 48 unrelated Japanese patients with late-onset bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, and performed genetic analysis of 63 known deafness gene using massively parallel DNA sequencing. As a result, we identified 25 possibly causative variants in 29 patients (60.4%). The present results clearly indicated that various genes are involved in late-onset hearing loss and a significant portion of cases of late-onset hearing loss is due to genetic causes. In addition, we identified two interesting cases for whom we could expand the phenotypic description. One case with a novel MYO7A variant showed a milder phenotype with progressive hearing loss and late-onset retinitis pigmentosa. The other case presented with Stickler syndrome with a mild phenotype caused by a homozygous frameshift COL9A3 variant. In conclusion, comprehensive genetic testing for late-onset hearing loss patients is necessary to obtain accurate diagnosis and to provide more appropriate treatment for these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is one of the most common sensory disorders in humans [1, 2]. The incidence of the congenital SNHL is estimated to be 1–2 in 1000 newborns, among which at least 60% are presumed to be associated with genetic causes [3]. Sloan-Heggen et al. undertook the genetic analysis of congenital deafness patients by targeted genomic enrichment with massively parallel DNA sequencing (TGE + MPS) and identified the causative gene mutations in 44% of cases [3]. In Japan, Mori et al. reported that the diagnostic rate was 41% in congenital or early-onset (<6 year) hearing loss (HL) patients based on screening for 154 mutations in 19 deafness genes using MPS combined with Invader assay and TaqMan genotyping [4]. On the other hand, these studies also reported that the diagnostic rates in late-onset hearing loss patients were lower than those in early-onset patients (28% and 16%, respectively) [3, 4]. Late-onset SNHL is believed to be a complex disorder, associated with age-related hearing loss, idiopathic sudden SNHL, acoustic neuroma, chronic otitis media or environmental risk factors (including noise exposure and ototoxic drug exposure). However, a certain number of late-onset bilateral symmetrical HL cases are thought to involve genetic factors, particularly in those with progressive HL presenting as worse than the average hearing for age. At present, a majority of late-onset SNHL cases do not receive genetic testing; thus, the etiology of late-onset SNHL remains largely unknown.

In this study we focused on late-onset bilateral SNHL patients and aimed to show the frequency of hereditary HL as well as describe the clinical features of these cases.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine (Approval number:170081). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Genetic Tests and Diagnoses in Medical Practice of the Japanese Association of Medical Sciences and the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Subjects

Sixty-four unrelated patients with bilateral SNHL were enrolled in this study. We defined late-onset HL as the HL with an age at onset of 6 years of age and over and, based on this definition, we excluded cases with congenital or pre-lingual onset SNHL (with an age at onset of under 6 years of age). In addition, we also excluded patients aged over 60 years at SNHL onset to remove cases of presbycusis. Finally, 48 unrelated Japanese patients with late-onset bilateral SNHL who underwent clinical genetic testing between April 2012 and April 2020 at Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine participated in this study (Table 1).

Clinical evaluations

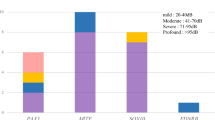

Hearing thresholds were evaluated using pure-tone audiometry (PTA) and classified by pure-tone average over 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. The severity of HL was classified into mild (21–40 dB HL), moderate (41–70 dB HL), severe (71–95 dB HL), and profound (>95 dB HL). The audiometric configurations were categorized into low-frequency, mid-frequency (U-shaped), high-frequency (gently sloping type and steeply sloping type), flat type, and deaf, as reported previously [5]. The data for age at onset of HL, the progressiveness of HL and family history were obtained from medical charts.

Amplicon resequencing and variant annotation

Amplicon libraries were prepared using an Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel for 68 genes reported to cause non-syndromic hereditary HL (ThermoFisher Scientific, MA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The detailed protocol has been described elsewhere [6]. MPS was performed with an Ion Proton system using an Ion HiQ Chef Kit and an Ion P1 Chip (ThermoFisher Scientific). The sequence data were mapped against the human genome sequence (build GRCh37/hg19) with a Torrent Mapping Alignment Program. After sequence mapping, the DNA variant regions were piled up with Torrent Variant Caller plug-in software. After variant detection, their effects were analyzed using ANNOVAR software [7, 8]. The missense, nonsense, insertion/deletion and splicing variants were selected from among the identified variants. Variants were further selected as less than 1% of: (1) the 1000 genome database, (2) 6500 exome variants, (3) the Human Genetic Variation Database (a dataset for 1208 Japanese exome variants), and (4) 333 in-house Japanese normal hearing controls. This filtering process was performed using our original database software described elsewhere [9]. The pathogenicity of selected variants was evaluated by American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) standards and guidelines [10]. For missense variants, in particular, functional prediction software, including Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant (SIFT), Polymorphism Phenotyping (PolyPhen2), LRT, Mutation Taster, Mutation Assessor, REVEL, and CADD, were used through the ANNOVAR software program [7, 8]. Direct sequencing was utilized to confirm the selected variants. Copy number variation (CNV) analysis was performed by using the read depth data with our published copy number variation detection method for Ion AmpliSeq enrichment and Ion PGM/Proton/S5 sequencing as described previously [11]. All genetic analyses were performed in Shinshu University School of Medicine as a collaborative study.

Results

Patient characteristics and identified variants

The age at onset of participants ranged from 6 to 60 years. Among them, 9 cases experienced onset in their 1st decade (6–10 years old) and the other 42 cases experienced onset in their 2nd decade or later (11–60 years old), accounting for 81.2% of all participants (Table 1).

As for the audiometric configuration, flat-type HL was the most common, being observed in 15 cases (31.3%), followed by 13 cases with gently sloping-type HL (27.1%), 10 cases with steeply sloping-type HL (20.8%), three cases with profound-type HL (6.3%), three cases with U-shaped-type HL (6.3%), and four cases with different types of HL in the left and right ears (Table 1).

We identified 25 possibly disease-causing variants from 29 probands, affording a diagnostic rate for this study of 60.4%. The most prevalent causative gene for late-onset HL in this study was a mitochondrial m.3243A>G mutation, which was observed in 6 cases, followed by four cases with COCH gene variants, three cases each with CDH23, KCNQ4 and MYO6 variants, two cases with EYA4 variants, and one case each with ACTG1, COL9A3, GJB2, MYO7A, POU4F3, STRC, USH2A, and mitochondria m.1555A>G variants (Table 2). Among the 25 identified variants, 18 had been reported previously as causative variants, and 7 were novel variants (Table 2). The novel variants consisted of two missense variants, one nonsense variant, three frameshift variants and one splicing variant. Based on the ACMG guidelines, the novel variants were categorized as pathogenic (1), likely pathogenic (7) and variants of uncertain significance variant (1) (Table 3).

Clinical features of patients with novel variants

Table 3 and Fig. 1 summarize the clinical features of the 7 individuals with novel variants.

Case 1 is a 43-year-old male. At around the age of 20, he experienced repeated episodes of dizziness and his HL gradually progressed. His mother had also experienced repeated episodes of dizziness with HL when she was in her twenties. Genetic analysis of this patient identified a heterozygous COCH gene missense variant (COCH: NM_004086:c.236A>G:p.H79R). His mother was found to carry the same variant.

Case 2 is a 61-year-old female who became aware of a loss of vision and HL in her thirties. She was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa through ophthalmological testing. Her HL gradually progressed and she was clinically suspected of Usher syndrome. She had never experienced any episodes of vertigo. Genetic analysis of this patient identified compound heterozygous USH2A gene splicing variants. USH2A: NM_206933:c.8559-2A>G was previously reported as a pathogenic variant of Usher syndrome type 2, and the other is novel splicing variant (NM_206933:exon36:c.6806-2A>C).

Case 3 is a 37-year-old female. She visited an otolaryngologist with a chief complaint of tinnitus and was diagnosed with HL when she was aged 35. Her audiometric configuration was of the gently sloping type at first, but HL progressed gradually even in the lower frequencies. She complained of dizziness about once every two years. Her father also had the same type of HL. Genetic analysis of this patient identified a heterozygous KCNQ4 frameshift variant (KCNQ4: NM_004700:c.1656dupA:p.L553Tfs*11).

Case 4 is a 52 -year-old female, with HL diagnosed during a checkup at the age of 40. She started to use hearing aids at the age of 50. Her mother, brother and sister had also experienced HL from their forties, and they also used hearing aids. Genetic analysis of this patient identified a heterozygous EYA4 gene frameshift variant (EYA4: NM_004100:c.1777delG:p.G593Afs*4).

Case 5 is a 33-year-old female, with a history of HL from the age of 27. Her HL progressed with age. Her mother had suffered HL from her forties. Her youngest sister had also suffered HL from elementary school. Genetic analysis of this patient identified a heterozygous MYO6 gene nonsense variant (MYO6: NM_004999: c.2393G>A:p.W798X). Her mother and sisters also carried the same variant. Her middle sister is presumed not to have developed HL yet.

Case 6 is a 47 -year-old male, diagnosed with HL during a checkup at age 7, who started wearing hearing aids when he was 10 years old. His HL was considered to be gradually progressive. He had no episodes of vertigo. The genetic testing revealed compound heterozygous variants in the MYO7A gene. MYO7A: NM_000260:c.1667G>T:p.G556V was previously reported [12] as a causative variant for retinitis pigmentosa and other is the novel variant MYO7A: NM_000260:c.1369G>A:p.A457T. His father had normal hearing and had only the c.1369G>A variant, thus these two variants are in the trans allele. We therefore recommended him to visit the department of ophthalmology, and he was diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa. He received a cochlear implant (CI) in the left ear at the age of 48 to benefit future communication. CI was effective for this case and his ability to understand speech was improved.

Case 7 is a 58-year-old female, diagnosed with HL in her twenties. Her parents were first cousins and her elder sister also had HL. Genetic analysis of this patient identified a homozygous COL9A3 gene frame-shift variant (COL9A3: NM_001853:c.1587dupT:p.G530Wfs*71).

This patient did not have any arthritis, but had cataracts and retinal detachment, which are known to be associated with Stickler syndrome.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed 48 late-onset SNHL patients, and identified 25 possibly disease-causing variants in 29 cases (60.4%). Among the 25 identified variants, 7 were novel. Genetic testing for HL, particularly in congenital or early-onset cases, is now widely available due to its clinical benefits in providing accurate diagnosis, prediction of HL severity, estimation of associated symptoms, selection of appropriate habilitation options, prevention of HL, and better genetic counseling [13]. In this study we confirmed the usefulness of genetic testing for late-onset HL cases, even though it is not commonly performed at present.

The diagnostic rate (60.4%) in this study was higher than those of previous studies (28% and 16%) [3, 4]. As our institution is a university hospital (tertiary referral hospital), and many cases in this study have multiple affected family members, it might explain the increased diagnostic ratio of this cohort. Indeed, 45.8 % (22/48) of our cohort have affected family members. In a previous study, the diagnostic rate in sporadic cases was 19%, which was lower than that of autosomal recessive or autosomal dominant cases (35% and 35%, respectively) [14]. In addition, our cohort also included the patients with a maternal family history of suspected mitochondrial disorders, which may also have increased the diagnostic rate. Mitochondrial mutations (m.1555A>G or m.3243A>G) were identified in 15% (7/48) of patients in this study. As another cause of the higher diagnostic rate, our cohort included many cases with progressive HL. In a previous study, the diagnostic rate for progressive HL cases was higher than that for stable HL cases [14]. These factors may have led to the higher diagnostic rate in this study. From a diagnostic perspective, these clinical characteristics will be useful for the selection of candidates for genetic testing to increase the diagnostic yield and efficiency.

A previous paper showed that the responsible genes differ between congenital or early-onset HL and late-onset HL [4]. In this study, we also identified many causative genes which was reported as genetic causes of late-onset and/or progressive HL, such as the KCNQ4, COCH, CDH23, EYA4, MYO7A, MYO6, ACTG1 and mitochondrial genes. As HL due to these genes is more or less progressive, the most appropriate therapeutic option from among hearing aids, electric acoustic stimulation (EAS), and cochlear implantation (CI) needs to be considered. Etiology as well as rate of progression is important to decision making, and genetic testing can provide this information [15]. If the etiology is located within the cochlea, good performance can be expected after CI [15].

The CDH23 gene is known to cause either Usher syndrome type 1D (USH1D) or non-syndromic HL (DFNB12). The phenotype range of CDH23-associated HL varies from congenital profound HL to adult-onset high-frequency-involved HL [16]. CI has been applied for patients with insufficient amplification by hearing aids, and EAS devices are a good therapeutic option for patients with residual hearing [15, 17, 18]. In this study, two of three DFNB12 cases who did not have sufficient amplification by hearing aids received CI and showed good performance.

The MYO7A gene is known to cause autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive non‐syndromic HL (DFNA11/DFNB2) as well as Usher syndrome (USH1B), [19, 20] which is characterized by congenital, bilateral, profound sensorineural HL, vestibular areflexia, and adolescent-onset retinitis pigmentosa (RP). In this study, we identified one case (Case 6) with compound heterozygous MYO7A variants who showed progressive HL and late-onset RP. His clinical phenotype of HL and RP was milder than that of typical USH1B cases. The novel variant MYO7A: c.1369G>A: p.A457T may cause a milder phenotype than that described in previous reports and cause a similar phenotype to that of Usher syndrome type III. The type classification in Usher syndrome is traditionally classified on the basis of clinical symptoms, not by the causative gene. Therefore, it is highly possible that new clinical phenotypes will emerge as information regarding the causative gene becomes clearer. This case is a good example of such phenotypic expansion.

The ACTG1 gene is known as a genetic cause of autosomal dominant non‐syndromic HL (ADNSHL) (DFNA20/26). In previous reports, most cases of ACTG1-associated HL showed onset in the first or second decade, with the first group showing high-frequency HL progressing in all frequencies [21, 22]. In this study, the patient with ACTG1: c.833C>T:p.T278I variants became aware of her HL at age 30. Her hearing level thereafter gradually progressed to a profound level. Her son also carried the same variant and showed a similar phenotype. He received CI at the age of 40, and showed good performance after implantation.

The EYA4 gene is known as a genetic cause of ADNSHL (DFNA10). The audiometric configuration for EYA4-associated HL was gradual high-frequency HL or flat-type HL [23, 24]. In this study, we identified two patients with different frame-shift variants. The age at onset of HL in these cases was in the 40 s, and the severity of HL was moderate to severe. The audiometric configuration types were flat and gently sloping, respectively, similar to those in previous reports.

The COCH gene is known to cause autosomal dominant and late-onset progressive sensorineural HL with vestibular dysfunction (DFNA9) [25, 26]. We identified four cases with COCH variants, and 3 of them carried the same variant (c.1115T>C:p. I372T). This variant has also been reported previously [27]. The same variant was reported from different Japanese ADNSHL families, and this variant may have spread from the same founder (founder mutation). Cochlin, the product of the COCH gene, has one LCCL domain and two vWFA domains. A mutation in the LCCL domain is reported to cause vertigo/dizziness more frequently than that in the vWFA domains [27]. The c.236A>G:p.H79R variant, which was identified as a novel variant in this study, is located in the LCCL domain. The phenotype of this case and his mother was late-onset progressive HL and dizziness, as previously reported.

The MYO6 gene is known to be responsible for both ADNSHL (DFNA22) and ARNSHL (DFNB37) [28]. In a previous study, patients with MYO6 variants showed late-onset mild-to-moderate progressive HL, and marked hearing deterioration occurred after the age of 40 [29]. In our study, the phenotypes of MYO6-associated HL varied as shown in Table 2.

The KCNQ4 gene is known to be one of the most frequent causative genes for ADNSHL (DFNA2) [30]. It has been shown that DFNA2 results in high-frequency-involved HL. A progressive nature is a common feature among patients with KCNQ4 mutations, regardless of the variant [31]. In this study, we identified 3 families with KCNQ4 variants, with one of them being a novel frameshift variant (c.1656dupA:p.L553Tfs*11). The audiometric configuration of this patient showed sensorineural hearing impairment involving all frequencies.

As a notable result, we also identified one case of phenotypically mild Stickler syndrome with a homozygous COL9A3 frameshift variant. The COL9A3 gene, first reported as a genetic cause of multiple epiphyseal dysplasia, an autosomal dominant osteo-chondro-dysplasia, [32] was also shown to be responsible for Stickler syndrome in two previous reports [33, 34]. Faletra et al., reported an autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome family with three affected siblings, all of whom carried a homozygous frameshift variant in the COL9A3 gene. All three individuals showed high-frequency HL and moderate-to-high myopia and amblyopia. Among the three affected siblings, the two elder brothers showed flat midface hypoplasia and a depressed nasal bridge, but the youngest sister in this family did not show these malformations. Hanson-Kahn et al., reported a patient with Stickler syndrome, who carried a homozygous COL9A3 frameshift variant and showed moderate-to-severe sensorineural HL, severe myopia, and both tibial and femoral bowing at birth [34]. As COL9A3 variants have been reported to cause non-syndromic HL [35], COL9A3 variants may have a broad phenotypic range from mild non-syndromic HL to more severe syndromic phenotypes. Due to inter- and intra-familial phenotypic variability [34, 35], it is extremely difficult to perform diagnosis based on clinical phenotypes. The present case, the third reported to date, presenting only with HL, cataract and retinal detachment, can be classified as a very mild type of Stickler syndrome that could not be diagnosed without genetic diagnosis. At her first visit, she was diagnosed with non-syndromic HL as she had no noticeable symptoms. Later, however, as the COL9A3 mutation was identified by genetic analysis, a detailed anamnestic re-evaluation of the associated symptoms of Stickler syndrome revealed a history of cataract and retinal detachment.

In conclusion, we performed genetic analysis of 48 Japanese patients with late-onset bilateral SNHL and identified the potential genetic causes of HL in 29 cases (60.4%). The present results clearly indicated that a significant portion of cases of late-onset bilateral SNHL may involve genetic causes, and the various causative genes can possibly be identified. From an etiological perspective, we could confirm the benefits of CI in cases in which the etiology is located within the cochlea, as shown in the MYO7A- and the ACTG1-associated cases. In addition, we could expand phenotypic descriptions as seen in (1) the MYO7A-associated case with a milder phenotype of Usher syndrome and (2) the phenotypically mild Stickler syndrome caused by a homozygous frameshift variant in the COL9A3 gene. These two cases could not be diagnosed without genetic testing. Therefore, comprehensive genetic testing can be seen as a useful diagnostic tool for late-onset HL, and the accumulation of genetic findings will enable more accurate diagnosis and provide more appropriate treatment.

References

Mehra S, Eavey RD, Keamy DG. The epidemiology of hearing impairment in the United States: newborns, children, and adolescents. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140:461–72.

Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening-a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2151–64.

Sloan-Heggen CM, Bierer AO, Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Nishimura CJ, Frees KL, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing in the clinical evaluation of 1119 patients with hearing loss. Hum Genet. 2016;135:441–50.

Mori K, Moteki H, Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Usami S. Social health insurance-based simultaneous screening for 154 mutations in 19 deafness genes efficiently identified causative mutations in japanese hearing loss patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162230.

Mazzoli M, Camp GV, Newton V, Giarbini N, Declau F, Parving A. Recommendations for the description of genetic and audiological data for families with nonsyndromic hereditary hearing impairment. Audiological Med. 2009;1:148–50.

Nishio SY, Hayashi Y, Watanabe M, Usami S. Clinical application of a custom AmpliSeq library and ion torrent PGM sequencing to comprehensive mutation screening for deafness genes. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2015;19:209–17.

Chang X, Wang K. wANNOVAR: annotating genetic variants for personal genomes via the web. J Med Genet. 2012;49:433–6.

Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164.

Nishio SY, Usami SI. The clinical next-generation sequencing database: a tool for the unified management of clinical information and genetic variants to accelerate variant pathogenicity classification. Hum Mutat. 2017;38:252–9.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Nishio SY, Moteki H, Usami SI. Simple and efficient germline copy number variant visualization method for the Ion AmpliSeq™ custom panel. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018 Apr.

Bankondi B, Lv W, Lu B, Jones MK, Tsai Y, Kim KJ, et al. In vivo CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing corrects retinal dystrophy in the S334ter-3 rat model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther. 2016;24:556–63.

Shearer AE, Hildebrand MS, Smith RJH. Hereditary hearing loss and deafness overview. 1999 Feb [Updated 2017 Jul 27]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1434/.

Moteki H, Azaiez H, Booth KT, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing with ethnic-specific filtering by allele frequency in a Japanese hearing-loss population. Clin Genet. 2016;89:466–72.

Usami SI, Nishio SY, Moteki H, Miyagawa M, Yoshimura H. Cochlear implantation from the perspective of genetic background. Anat Rec. 2020;303:563–93.

Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Usami S. Prevalence and clinical features of hearing loss patients with CDH23 mutations: a large cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40366.

Usami S, Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, et al. Patients with CDH23 mutations and the 1555A>G mitochondrial mutation are good candidates for electric acoustic stimulation (EAS). Acta Otolaryngol. 2012;132:377–84.

Yoshimura H, Moteki H, Nishio SY, Miyajima H, Miyagawa M, Usami SI. Genetic testing has the potential to impact hearing preservation following cochlear implantation. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140:438–44.

Liu XZ, Walsh J, Mburu P, et al. Mutations in the myosin VIIA gene cause non-syndromic recessive deafness. Nat Genet. 1997;16:188–90.

Weil D, Küssel P, Blanchard S, et al. The autosomal recessive isolated deafness, DFNB2, and the Usher 1B syndrome are allelic defects of the myosin-VIIA gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:191–3.

Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Ichinose A, et al. Mutational spectrum and clinical features of patients with ACTG1 mutations identified by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124:84S–93S.

Miyajima H, Moteki H, Day T, Nishio SY, Murata T, Ikezono T, et al. Novel ACTG1 mutations in patients identified by massively parallel DNA sequencing cause progressive hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2020;10:7056.

Shinagawa J, Moteki H, Nishio SY, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of hearing loss caued by EYA4 variants. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3662.

De Leenheer EM, Huygen PL, Wayne S, Smith RJ, Cremers CW. The DFNA10 phenotype. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:861–6.

Robertson NG, Khetarpal U, Gutiérrez-Espeleta GA, Bieber FR, Morton CC. Isolation of novel and known genes from a human fetal cochlear cDNA library using subtractive hybridization and differential screening. Genomics. 1994;23:42–50.

Kemperman MH, Bom SJ, Lemaire FX, Verhagen WI, Huygen PL, Cremers CW. DFNA9/COCH and its phenotype. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;61:66–72.

Tsukada K, Ichinose A, Miyagawa M, et al. Detailed hearing and vestibular profiles in the patients with COCH mutations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124:100S–10S.

Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Kumakawa K, Usami S. Massively parallel DNA sequencing successfully identified seven families with deafness-associated MYO6 mutations: the mutational spectrum and clinical characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2015;124:148S–57S.

Oka SI, Day TF, Nishio SY, et al. Clinical characteristics and in vitro analysis of MYO6 variants causing late-onset progressive hearing loss. Genes. 2020;11:273.

Hilgert N, Smith RJ, Van, Camp G. Function and expression pattern of nonsyndromic deafness genes. Curr Mol Med. 2009;9:546–64.

Naito T, Nishio SY, Iwasa Y, et al. Comprehensive genetic screening of KCNQ4 in a large autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss cohort: genotype-phenotype correlations and a founder mutation. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63231.

Paassilta P, Lohiniva J, Annunen S, et al. COL9A3: A third locus for multiple epiphyseal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64:1036–44.

Faletra F, D'Adamo AP, Bruno I, et al. Autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome due to a loss of function mutation in the COL9A3 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:42–7.

Hanson-Kahn A, Li B, Cohn DH, et al. Autosomal recessive Stickler syndrome resulting from a COL9A3 mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:2887–91.

Asamura K, Abe S, Fukuoka H, Nakamura Y, Usami S. Mutation analysis of COL9A3, a gene highly expressed in the cochlea, in hearing loss patients. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2005;32:113–7.

van den Ouweland JM, Lemkes HH, Ruitenbeek W, et al. Mutation in mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene in a large pedigree with maternally transmitted type II diabetes mellitus and deafness. Nat Genet. 1992;1:368–71.

Wagatsuma M, Kitoh R, Suzuki H, Fukuoka H, Takumi Y, Usami S. Distribution and frequencies of CDH23 mutations in Japanese patients with non-syndromic hearing loss. Clin Genet. 2007;72:339–44.

Ahmed ZM, Morell RJ, Riazuddin S, et al. Mutations of MYO6 are associated with recessive deafness, DFNB37. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1315–22.

Yang T, Wei X, Chai Y, Li L, Wu H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:85.

Kamada F, Kure S, Kudo T, et al. A novel KCNQ4 one-base deletion in a large pedigree with hearing loss: implication for the genotype-phenotype correlation. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:455–60.

Coucke PJ, Van Hauwe P, Kelley PM, et al. Mutations in the KCNQ4 gene are responsible for autosomal dominant deafness in four DFNA2 families. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1321–8.

Abe S, Usami S, Shinkawa H, Kelley PM, Kimberling WJ. Prevalent connexin 26 gene (GJB2) mutations in Japanese. J Med Genet. 2000;37:41–3.

Fuse Y, Doi K, Hasegawa T, Sugii A, Hibino H, Kubo T. Three novel connexin26 gene mutations in autosomal recessive non-syndromic deafness. Neuroreport. 1999;10:1853–7.

Prezant TR, Agapian JV, Bohlman MC, et al. Mitochondrial ribosomal RNA mutation associated with both antibiotic-induced and non-syndromic deafness. Nat Genet. 1993;4:289–94.

Kitano T, Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, et al. POU4F3 mutation screening in Japanese hearing loss patients: Massively parallel DNA sequencing-based analysis identified novel variants associated with autosomal dominant hearing loss. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177636.

Yokota Y, Moteki H, Nishio SY, et al. Frequency and clinical features of hearing loss caused by STRC deletions. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4408.

Dai H, Zhang X, Zhao X, et al. Identification of five novel mutations in the long isoform of the USH2A gene in Chinese families with Usher syndrome type II. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2067–75.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Research on Rare and Intractable Diseases and Comprehensive Research on Disability Health and Welfare from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan (S.U.:20FC1048), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (N.U.:19K18768) and a Grant-in-Aid from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (S.U.:20ek0109363h0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the study, N.U.; Performed the experiments, N.U., D.Y., T.F., S.N., S.K.; Analyzed data: N.U., J.Y., A.K., S.N.; Writing-original draft, N.U.; Writing—review and editing, N.U., N.K., S.U.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Uehara, N., Fujita, T., Yamashita, D. et al. Genetic background in late-onset sensorineural hearing loss patients. J Hum Genet 67, 223–230 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-021-00990-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-021-00990-2

This article is cited by

-

Late-onset, progressive sensorineural hearing loss in the paediatric population: a systematic review

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2024)