Abstract

Background/objectives

Adverse effects of topical glaucoma medications (TGMs) may include development of ocular adnexal disorders. We undertook a study to determine the effect of TGMs on the risk of developing lacrimal drainage obstruction (LDO) and eyelid malposition.

Subjects/methods

All patients 66 years of age and older in Ontario, Canada initiating TGM and all patients diagnosed with glaucoma/suspected glaucoma but not receiving TGM from 2002 to 2018 were eligible for inclusion in this retrospective cohort study. Using validated healthcare administrative databases, cohorts were identified with TGM and no TGM patients matched 1:2 on sex and birth year. The effect of TGM treatment on risk of surgery for LDO and lid malpositions was estimated using Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

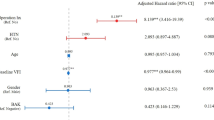

Cohorts included 122,582 patients in the TGM cohort and 232,336 patients in the no TGM cohort. Among the TGM cohort there was decreased event-free survival for entropion (log-rank P < 0.001), trichiasis (P < 0.001), and LDO (P = 0.006), and increased ectropion-free survival (P = 0.007). No difference in ptosis-free survival was detected (P = 0.78). For the TGM cohort there were increased hazards for entropion (hazard ratio [HR] 1.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.12–1.37; P < 0.001), trichiasis (HR 1.74, 95% CI 1.57–1.94; P < 0.001), and LDO (at 15 years: HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.49–3.85; P = 0.004), and a decreased hazard for ectropion (HR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.97; P = 0.008). No association between TGM treatment and ptosis hazard was detected (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.89–1.09; P = 0.78).

Conclusions

TGMs are associated with an increased risk of undergoing surgery for LDO, entropion, and trichiasis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 18 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $14.39 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The dataset from this study is held securely in coded form at ICES. While data sharing agreements prohibit ICES from making the dataset publicly available, access may be granted to those who meet pre-specified criteria for confidential access, available at www.ices.on.ca/DAS. The full dataset creation plan and underlying analytic code are available from the authors upon request, understanding that the computer programs may rely upon coding templates or macros that are unique to ICES and are therefore either inaccessible or may require modification.

References

Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2005.081224.

Weinreb RN, Aung T, Medeiros FA. The pathophysiology and treatment of glaucoma: A review. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1901–11.

Prum BE, Rosenberg LF, Gedde SJ, Mansberger SL, Stein JD, Moroi SE, et al. Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma Preferred Practice Pattern® Guidelines. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:P41–111.

Quinn MP, Johnson D, Whitehead M, Gill SS, Campbell RJ. Predictors of Initial Glaucoma Therapy with Laser Trabeculoplasty versus Medication. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2021;4:358–64. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S258941962030301X.

Servat JJ, Bernardino CR. Effects of Common Topical Antiglaucoma Medications on the Ocular Surface, Eyelids and Periorbital Tissue. Drugs Aging. 2011;28:267–82. https://doi.org/10.2165/11588830-000000000-00000.

Gazzard G, Konstantakopoulou E, Garway-Heath D, Garg A, Bunce C, Wormald R, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus eye drops for first-line treatment of ocular hypertension and glaucoma (LiGHT): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;393:1505–16.

Saheb H, Ahmed IIK. Micro-invasive glaucoma surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:96–104. https://journals.lww.com/00055735-201203000-00004.

Beckers HJM, Schouten JSAG, Webers CAB, van der Valk R, Hendrikse F. Side effects of commonly used glaucoma medications: comparison of tolerability, chance of discontinuation, and patient satisfaction. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:1485–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-008-0875-7.

McNab AA. Lacrimal canalicular obstruction associated with topical ocular medication. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1998;26:219–23.

Seider N, Miller B, Beiran I. Topical Glaucoma Therapy as a Risk Factor for Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:120–3. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002939407006897.

Kashkouli MB, Rezaee R, Nilforoushan N, Salimi S, Foroutan A, Naseripour M. Topical Antiglaucoma Medications and Lacrimal Drainage System Obstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:172–5. https://journals.lww.com/00002341-200805000-00002.

Britt MT, Burnstine MA. Iopidine allergy causing lower eyelid ectropion progressing to cicatricial entropion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:992–3.

Bearden W, Anderson R. Trichiasis Associated With Prostaglandin Analog Use. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:320–2. https://journals.lww.com/00002341-200407000-00015.

D’Ostroph AO, Dailey RA. Cicatricial Entropion Associated With Chronic Dipivefrin Application. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;17:328–31. http://journals.lww.com/00002341-200109000-00006.

Golan S, Rabina G, Kurtz S, Leibovitch I. The prevalence of glaucoma in patients undergoing surgery for eyelid entropion or ectropion. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1429–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S97694. Accessed 24 May 2020.

Aristodemou P, Baer R. Reversible Cicatricial Ectropion Precipitated by Topical Brimonidine Eye Drops. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:57–8. http://journals.lww.com/00002341-200801000-00018.

Hegde V, Robinson R, Dean F, Mulvihill HA, Ahluwalia H. Drug-Induced Ectropion. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:362–6. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0161642006014503. Accessed 24 May 2020.

Bartley GB. Reversible lower eyelid ectropion associated with dipivefrin. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;111:650–1.

Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Philip Miller J, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: A randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–13.

Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Hyman L, Bengtsson B, Hussein M. Reduction of intraocular pressure and glaucoma progression: Results from the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:1268–79.

Gaasterland DE, Ederer F, Beck A, Costarides A, Leef D, Closek J, et al. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:429–40.

Lichter PR, Musch DC, Gillespie BW, Guire KE, Janz NK, Wren PA, et al. Interim clinical outcomes in the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study comparing initial treatment randomized to medications or surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1943–53.

Anderson DR, Drance SM, Schulzer M. Comparison of glaucomatous progression between untreated patients with normal-tension glaucoma and patients with therapeutically reduced intraocular pressures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:487–97.

Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, Harron K, Moher D, Petersen I, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLOS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885.

Campbell RJ, Bell CM, Paterson JM, Bronskill SE, Moineddin R, Whitehead M, et al. Stroke rates after introduction of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors for macular degeneration: A time series analysis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1604–8.

Campbell RJ, Gill SS, Bronskill SE, Paterson JM, Whitehead M, Bell CM. Adverse events with intravitreal injection of vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors: nested case-control study. BMJ. 2012;345:e4203.

Quinn MP, Johnson D, Whitehead M, Gill SS, Campbell RJ. Distribution and Predictors of Initial Glaucoma Care Among Ophthalmologists and Optometrists: A Population-based Study. J Glaucoma. 2021;30:e300–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/IJG.0000000000001792.

Williams JI, Young W. A summary of studies on the quality of health care administration databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, Blackstien-Hirsh P, Fooks C, Naylor D, editors. Patterns of Health Care in Ontario: The ICES Practice Atlas. 2nd ed. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1996. pp. 339–45. https://www.ices.on.ca/~/media/Files/Atlases-Reports/1996/Patterns-of-health-care-in-Ontario-2nd-edition/Full-report.ashx.

Levy AR, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, Grootendorst P, Willison D. Coding accuracy of administrative drug claims in the Ontario Drug Benefit database. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;10:67–71.

Juurlink D, Preyra C, Croxford R, Chong A, Austin P, Tu J, et al. Canadian institute for health information discharge abstract database: a validation study. 2006. https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2006/Canadian-Institute-for-Health-Information. Accessed 29 April 2020.

Gruneir A, Bell CM, Bronskill SE, Schull M, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Frequency and pattern of emergency department visits by long-term care residents - A population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:510–7.

Gill SS, Anderson GM, Fischer HD, Bell CM, Li P, Normand SLT, et al. Syncope and its consequences in patients with dementia receiving cholinesterase inhibitors: A population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:867–73.

Campbell RJ, Bell CM, Gill SS, Trope GE, Buys YM, Whitehead M, et al. Subspecialization in glaucoma surgery. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2270–3.

Zhou Z, Rahme E, Abrahamowicz M, Pilote L. Survival Bias Associated with Time-to-Treatment Initiation in Drug Effectiveness Evaluation: A Comparison of Methods. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:1016–23. http://academic.oup.com/aje/article/162/10/1016/65057/Survival-Bias-Associated-with-TimetoTreatment.

Normand SLT, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, et al. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: A matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–98.

Austin PC, Mamdani MM. A comparison of propensity score methods: A case-study estimating the effectiveness of post-AMI statin use. Stat Med. 2006;25:2084–106.

Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–79.

Xie J, Liu C. Adjusted Kaplan–Meier estimator and log-rank test with inverse probability of treatment weighting for survival data. Stat Med. 2005;24:3089–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2174.

Austin PC. The performance of different propensity score methods for estimating marginal hazard ratios. Stat Med. 2013;32:2837–49. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sim.5705.

Allison PD. Survival analysis using SAS: a practical guide, second edition, 2nd ed. Cary, N.C: SAS Pub; 2010.

Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ 1999;319:1492–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1492.

Altman DG. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317:1309–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309.

Ohtomo K, Ueta T, Toyama T, Nagahara M. Predisposing factors for primary acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Graefe’s Arch. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2013;251:1835–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-013-2288-5.

Pisella PJ, Pouliquen P, Baudouin C, Grasso CM. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. Evid Based Eye Care. 2002;3:140–1.

Dart JK. The 2016 Bowman Lecture Conjunctival curses: scarring conjunctivitis 30 years on. Eye. 2017;31:301–32. http://www.nature.com/articles/eye2016284.

Broadway D, Grierson I, Hitchings R. Adverse effects of topical antiglaucomatous medications on the conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:590–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.77.9.590.

Thorne JE, Anhalt GJ, Jabs DA. Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid and Pseudopemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:45–52.

Shah M, Lee G, Lefebvre DR, Kronberg B, Loomis S, Brauner SC, et al. A Cross-Sectional Survey of the Association between Bilateral Topical Prostaglandin Analogue Use and Ocular Adnexal Features Boulton ME (ed). PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e61638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061638.

Sipkova Z, Vonica O, Olurin O, Obi EE, Pearson AR. Assessment of patientreported outcome and quality of life improvement following surgery for epiphora. Eye. 2017;31:1664–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2017.120.

Steven DW, Alaghband P, Lim KS. Preservatives in glaucoma medication. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:1497–503. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2017-311544.

Acknowledgements

Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by: the Ontario MOH and MLTC, Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database, Ontario Drug Benefit (ODB) database and IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc., Ontario Registered Persons Database, and ICES Physician Database. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred. We thank IQVIA Solutions Canada Inc. for use of their Drug Information Database. The authors thank Chad McClintock and Jonas Shellenberger for their contributions to the statistical analyses. Note: ICES Name change. In 2018, the institute formerly known as the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences formally adopted the initialism ICES as its official name. This change acknowledges the growth and evolution of the organization’s research since its inception in 1992, while retaining the familiarity of the former acronym within the scientific community and beyond.

Funding

This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Long-Term Care. Dr. Campbell is supported by the David Barsky Chair in Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MPQ was responsible for conception and design of the study, data acquisition and interpretation, drafting and revising the paper, approval of the final version, and overall study accountability. MW was responsible for study design, data acquisition, critical revision of the paper, approval of the final version, and overall study accountability. VK, SSG, and MAM were responsible for study design, data interpretation, critical revision of the paper, approval of the final version, and overall study accountability. RJC was responsible for conception and design of the study, data acquisition and interpretation, critical revision of the paper, approval of the final version, and overall study accountability.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Quinn, M.P., Kratky, V., Whitehead, M. et al. Association of topical glaucoma medications with lacrimal drainage obstruction and eyelid malposition. Eye 37, 2233–2239 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02322-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-022-02322-w