Abstract

The spatial distribution of mare basalts, titanium and KREEP (potassium, rare earth elements and phosphorus) on the Moon is asymmetrical between the nearside and farside. These asymmetries cannot be readily explained by solidification of a global magma ocean and subsequent mantle overturn, which should result in a layered and spherically symmetric lunar interior. Alternative scenarios have been proposed to explain the observed compositional asymmetry, but its origin remains enigmatic. Here, we present hydro- and mantle convection numerical simulations of the giant impact event that formed the South Pole–Aitken basin—the largest impact basin on the Moon—and the subsequent impact-induced convection with the assistance of gravitational instability. We find that the impact induces thermochemical instabilities that drive the dense KREEP-rich ilmenite-bearing cumulate to migrate towards the nearside following lunar magma ocean solidification. This results in the formation of a chemical reservoir under the nearside crust that could explain the observed geochemical asymmetries. We suggest that enrichments of ilmenite and KREEP in the nearside hemisphere following the South Pole–Aitken impact event provide a viable explanation for the wide composition range of mare basalts observed on the lunar surface.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data for the iSALE and CitcomS models required to reproduce key figures in this Article are provided in a Zenodo repository (SPA Overturn v2, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5652899). The element abundance data were retrieved from the Geosciences Node of NASA’s Planetary Data System (https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/lunar/lp-l-grs-5-elem-abundance-v1/lp_9001/data/), the albedo map from the Annex of PDS Cartography & Imaging Sciences Node (https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/Moon/Clementine/UVVIS/Lunar_Clementine_UVVIS_750nm_Global_Mosaic_118m_v2) and the mare boundaries from a digitized database (http://wms.lroc.asu.edu/lroc/view_rdr/SHAPEFILE_LROC_GLOBAL_MARE). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

At present, iSALE is not a fully open-source. It is distributed on a case by case basis to academic users in the impact community, strictly for non-commercial use. Scientists interested in using or developing iSALE should see http://www.isale-code.de for a description of application requirements. CitcomS is an open-source software available at Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics (https://geodynamics.org/cig/software/citcoms/).

References

Wood, J. A., Dickey, J. S., Marvin, U. B. & Powell, B. N. Lunar anorthosites. Science 167, 602–604 (1970).

Smith, J. V., Anderson, A. T., Newton, R. C., Olsen, E. J. & Wyllie, P. J. A petrologic model for the Moon based on petrogenesis, experimental petrology and physical properties. J. Geol. 78, 381–405 (1970).

Hess, P. C. & Parmentier, E. M. A model for the thermal and chemical evolution of the Moon’s interior: implications for the onset of mare volcanism. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 134, 501–514 (1995).

Li, H. et al. Lunar cumulate mantle overturn: a model constrained by ilmenite rheology. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 124, 1357–1378 (2019).

Parmentier, E. M., Zhong, S. & Zuber, M. T. Gravitational differentiation due to initial chemical stratification: origin of lunar asymmetry by the creep of dense KREEP? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 201, 473–480 (2002).

Lucey, P. G., Spudis, P. D., Zuber, M., Smith, D. & Malaret, E. Topographic-compositional units on the Moon and the early evolution of the lunar crust. Science 266, 1855–1858 (1994).

Garrick-Bethell, I., Nimmo, F. & Wieczorek, M. A. Structure and formation of the lunar farside highlands. Science 330, 949–951 (2010).

Lucey, P. G., Blewett, D. T. & Hawke, B. R. Mapping the FeO and TiO2 content of the lunar surface with multispectral imagery. J. Geophys. Res. 103, 3679–3699 (1998).

Prettyman, T. H. et al. Elemental composition of the lunar surface: analysis of gamma ray spectroscopy data from Lunar Prospector. J. Geophys. Res. 111, E12007 (2006).

Hiesinger, H., Head, J. W., Wolf, U., Jaumann, R. & Neukum, G. Ages and stratigraphy of lunar mare basalts: a synthesis. Geol. Soc. Am. Spec. Pap. 477, 1–51 (2011).

Wieczorek, M. A. & Phillips, R. J. The ‘Procellarum KREEP Terrane’: implications for mare volcanism and lunar evolution. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 20417–20430 (2000).

Jolliff, B. L., Gillis, J. J., Haskin, L. A., Korotev, R. L. & Wieczorek, M. A. Major lunar crustal terranes: surface expressions and crust-mantle origins. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 4197–4216 (2000).

Elphic, R. C. et al. Lunar rare earth element distribution and ramifications for FeO and TiO2: Lunar Prospector neutron spectrometer observations. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 20333–20345 (2000).

Zhong, S., Parmentier, E. M. & Zuber, M. T. A dynamic origin for the global asymmetry of lunar mare basalts. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 177, 131–140 (2000).

Zhang, N., Dygert, N., Liang, Y. & Parmentier, E. M. The effect of ilmenite viscosity on the dynamics and evolution of an overturned lunar cumulate mantle: ilmenite effects on the lunar upwellings. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 6543–6552 (2017).

Zhang, N., Parmentier, E. M. & Liang, Y. A 3-D numerical study of the thermal evolution of the Moon after cumulate mantle overturn: the importance of rheology and core solidification. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 1789–1804 (2013).

Wasson, J. T. & Warren, P. H. Contribution of the mantle to the lunar asymmetry. Icarus 44, 752–771 (1980).

Werner, C. L. & Loper, D. E. On lunar asymmetries 2. Origin and distribution of mare basalts and mascons. J. Geophys. Res. 107, 12-1–12-6 (2002).

Quillen, A. C., Martini, L. & Nakajima, M. Near/far side asymmetry in the tidally heated Moon. Icarus 329, 182–196 (2019).

Jutzi, M. & Asphaug, E. Forming the lunar farside highlands by accretion of a companion Moon. Nature 476, 69–72 (2011).

Zhu, M.-H., Wünnemann, K., Potter, R. W. K., Kleine, T. & Morbidelli, A. Are the Moon’s nearside-farside asymmetries the result of a giant impact? J. Geophys. Res. Planets 124, 2117–2140 (2019).

Orgel, C. et al. Ancient bombardment of the inner solar system: reinvestigation of the ‘fingerprints’ of different impactor populations on the lunar surface. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 123, 748–762 (2018).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Burgess, S. & Yin, Q.-Z. The lunar magma ocean: reconciling the solidification process with lunar petrology and geochronology. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 304, 326–336 (2011).

Borg, L. E., Gaffney, A. M. & Shearer, C. K. A review of lunar chronology revealing a preponderance of 4.34–4.37 Ga ages. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 715–732 (2015).

Morbidelli, A. et al. The timeline of the lunar bombardment: revisited. Icarus 305, 262–276 (2018).

Barboni, M. et al. Early formation of the Moon 4.51 billion years ago. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602365 (2017).

Garrick-Bethell, I. et al. Troctolite 76535: a sample of the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken basin? Icarus 338, 113430 (2020).

Garrick-Bethell, I. & Zuber, M. T. Elliptical structure of the lunar South Pole-Aitken basin. Icarus 204, 399–408 (2009).

Roberts, J. H. & Arkani-Hamed, J. Effects of basin-forming impacts on the thermal evolution and magnetic field of Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 478, 192–202 (2017).

Ghods, A. & Arkani-Hamed, J. Impact-induced convection as the main mechanism for formation of lunar mare basalts. J. Geophys. Res. 112, E03005 (2007).

Rolf, T., Zhu, M.-H., Wünnemann, K. & Werner, S. C. The role of impact bombardment history in lunar evolution. Icarus 286, 138–152 (2017).

Schultz, P. H. & Crawford, D. A. in Recent Advances and Current Research Issues in Lunar Stratigraphy: Geological Society of America Special Paper Vol. 477 (eds Ambrose, W. A. & Williams, D. A.) 141–159 (Geological Society of America, 2011).

Elbeshausen, D., Wünnemann, K. & Collins, G. S. The transition from circular to elliptical impact craters. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 2295–2309 (2013).

Zhong, S., McNamara, A., Tan, E., Moresi, L. & Gurnis, M. A benchmark study on mantle convection in a 3-D spherical shell using CitcomS. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q10017 (2008).

Wieczorek, M. A., Weiss, B. P. & Stewart, S. T. An impactor origin for lunar magnetic anomalies. Science 335, 1212–1215 (2012).

Potter, R. W. K., Collins, G. S., Kiefer, W. S., McGovern, P. J. & Kring, D. A. Constraining the size of the South Pole-Aitken basin impact. Icarus 220, 730–743 (2012).

Melosh, H. J. et al. South Pole-Aitken basin ejecta reveal the Moon’s upper mantle. Geology 45, 1063–1066 (2017).

Lin, Y., Tronche, E. J., Steenstra, E. S. & van Westrenen, W. Evidence for an early wet Moon from experimental crystallization of the lunar magma ocean. Nat. Geosci. 10, 14–18 (2017).

Dygert, N., Hirth, G. & Liang, Y. A flow law for ilmenite in dislocation creep: implications for lunar cumulate mantle overturn. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 532–540 (2016).

Zuber, M. T. et al. Gravity field of the Moon from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission. Science 339, 668–671 (2013).

Boukaré, C.-E., Parmentier, E. M. & Parman, S. W. Timing of mantle overturn during magma ocean solidification. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 491, 216–225 (2018).

Laneuville, M., Wieczorek, M. A., Breuer, D. & Tosi, N. Asymmetric thermal evolution of the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 118, 1435–1452 (2013).

Grove, T. L. & Krawczynski, M. J. Lunar mare volcanism: where did the magmas come from? Elements 5, 29–34 (2009).

Snyder, G. A., Taylor, L. A. & Neal, C. R. A chemical model for generating the sources of mare basalts: combined equilibrium and fractional crystallization of the lunar magmasphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 3809–3823 (1992).

Tokle, L., Hirth, G., Raterron, P. & Dygert, N. J. The pressure and Mg# dependence of ilmenite and ilmenite-olivine aggregate rheology: implications for the lunar cumulate mantle overturn. In 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Abstract 2070 (The Woodlands, TX, 2017).

Qin, C., Muirhead, A. C. & Zhong, S. Correlation of deep moonquakes and mare basalts: implications for lunar mantle structure and evolution. Icarus 220, 100–105 (2012).

Andrews-Hanna, J. C. et al. Structure and evolution of the lunar Procellarum region as revealed by GRAIL gravity data. Nature 514, 68–71 (2014).

Nyquist, L. E. & Shih, C.-Y. The isotopic record of lunar volcanism. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 56, 2213–2234 (1992).

Neal, C. R. et al. The Lunar Geophysical Network Mission. In AGU Fall Meeting P33D-05 (2019).

Hartmann, W. K. Megaregolith evolution and cratering cataclysm models—lunar cataclysm as a misconception (28 years later). Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 38, 579–593 (2003).

Marinova, M. M., Aharonson, O. & Asphaug, E. Mega-impact formation of the Mars hemispheric dichotomy. Nature 453, 1216–1219 (2008).

Thompson, S. L. & Lauson, H. S. Improvements in the Chart D Radiation-Hydrodynamic Code. III: Revised Analytic Equations of State. Technical Report SC-RR-71-0714 (US DOE, 1972).

Benz, W., Cameron, A. G. W. & Melosh, H. J. The origin of the Moon and the single-impact hypothesis III. Icarus 81, 113–131 (1989).

Collins, G. S., Melosh, H. J. & Ivanov, B. A. Modeling damage and deformation in impact simulations. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 39, 217–231 (2004).

Johnson, G. & Cook, W. H. A constitutive model and data for metals subjected to large strains, high strain rates and high temperatures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 21, 541–548 (1983).

Davison, T. M., Collins, G. S., Elbeshausen, D., Wünnemann, K. & Kearsley, A. Numerical modeling of oblique hypervelocity impacts on strong ductile targets: oblique hypervelocity impacts on ductile targets. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 46, 1510–1524 (2011).

Ivanov, B. A., Melosh, H. J. & Pierazzo, E. in Large Meteorite Impacts and Planetary Evolution IV Vol. 465 (Geological Society of America, 2010); https://doi.org/10.1130/2010.2465(03)

Miljković, K. et al. Asymmetric distribution of lunar impact basins caused by variations in target properties. Science 342, 724–726 (2013).

Zhu, M.-H., Wünnemann, K. & Artemieva, N. Effects of Moon’s thermal state on the impact basin ejecta distribution. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11292–11300 (2017).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. The crust of the Moon as seen by GRAIL. Science 339, 671–675 (2013).

Melosh, H. J. et al. The origin of lunar mascon basins. Science 340, 1552–1555 (2013).

Freed, A. M. et al. The formation of lunar mascon basins from impact to contemporary form. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 2378–2397 (2014).

Neumann, G. A. et al. Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements. Sci. Adv 1, e1500852 (2015).

Wieczorek, M. A. & Phillips, R. J. Lunar multiring basins and the cratering process. Icarus 139, 246–259 (1999).

Spudis, P. D. The Geology of Multi-Ring Impact Basins: The Moon and Other Planets (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993).

Lucey, P. G., Blewett, D. T. & Jolliff, B. L. Lunar iron and titanium abundance algorithms based on final processing of Clementine ultraviolet-visible images. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 20297–20306 (2000).

Goossens, S. et al. High-resolution gravity field models from GRAIL data and implications for models of the density structure of the Moon’s crust. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2019JE006086 (2020).

Hurwitz, D. M. & Kring, D. A. Differentiation of the South Pole-Aitken basin impact melt sheet: implications for lunar exploration. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 1110–1133 (2014).

Vaughan, W. M. & Head, J. W. Impact melt differentiation in the South Pole-Aitken basin: some observations and speculations. Planet. Space Sci. 91, 101–106 (2014).

Johnson, B. C. et al. Formation of the Orientale lunar multiring basin. Science 354, 441–444 (2016).

Trowbridge, A. J., Johnson, B. C., Freed, A. M. & Melosh, H. J. Why the lunar South Pole-Aitken basin is not a mascon. Icarus 352, 113995 (2020).

Citron, R. I., Manga, M. & Tan, E. A hybrid origin of the Martian crustal dichotomy: Degree-1 convection antipodal to a giant impact. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 491, 58–66 (2018).

Roberts, J. H. & Arkani-Hamed, J. Impact-induced mantle dynamics on Mars. Icarus 218, 278–289 (2012).

Roberts, J. H. & Arkani-Hamed, J. Impact heating and coupled core cooling and mantle dynamics on Mars: coupled core and mantle dynamics on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 729–744 (2014).

Watters, W. A., Zuber, M. T. & Hager, B. H. Thermal perturbations caused by large impacts and consequences for mantle convection. J. Geophys. Res. 114, E02001 (2009).

Pierazzo, E. & Melosh, H. J. Melt production in oblique impacts. Icarus 145, 252–261 (2000).

Melosh, H. J. Impact Cratering: a Geologic Process (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

Manske, L., Marchi, S., Plesa, A. & Wunnemann, K. Impact melting upon basin formation on Mars. Icarus 357, 114128 (2021).

Uemoto, K. et al. Evidence of impact melt sheet differentiation of the lunar South Pole-Aitken basin. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 122, 1672–1686 (2017).

Tackley, P. J. & King, S. D. Testing the tracer ratio method for modeling active compositional fields in mantle convection simulations. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 4, 8302 (2003).

Elkins-Tanton, L. T., Van Orman, J. A., Hager, B. H. & Grove, T. L. Re-examination of the lunar magma ocean cumulate overturn hypothesis: melting or mixing is required. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 196, 239–249 (2002).

Borg, L. E., Connelly, J. N., Boyet, M. & Carlson, R. W. Chronological evidence that the Moon is either young or did not have a global magma ocean. Nature 477, 70–72 (2011).

Snape, J. F. et al. Lunar basalt chronology, mantle differentiation and implications for determining the age of the Moon. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 451, 149–158 (2016).

Taylor, S. R. Planetary Science: a Lunar Perspective (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 1982).

Albarède, F., Albalat, E. & Lee, C.-T. A. An intrinsic volatility scale relevant to the Earth and Moon and the status of water in the Moon. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50, 568–577 (2015).

Wang, K. & Jacobsen, S. B. Potassium isotopic evidence for a high-energy giant impact origin of the Moon. Nature 538, 487–490 (2016).

Laneuville, M., Taylor, J. & Wieczorek, M. A. Distribution of radioactive heat sources and thermal history of the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 123, 3144–3166 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for discussions with Y. Liang, E. M. Parmentier and S. Zhong. We acknowledge the developers of iSALE-3D and thank the Computational Infrastructure for Geodynamics for distributing CitcomS software. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China via grant no. 41674098 and pre-research project of the Civil Aerospace Technologies of China National Space Administration grant no. D020205 (to N.Z.), Macau Science and Technology Development Fund grant no. 0020/2021/A1, National Natural Science Foundation of China grant no. 12173106 and pre-research project on Civil Aerospace Technologies of China National Space Administration grant no. D020303 (to M.D.), Macau Science and Technology Development Fund 0079/2018/A2 and pre-research project on Civil Aerospace Technologies of China National Space Administration grant no. D020202 (to M.-H.Z.) and Strategic Priority Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences grant no. XDB41000000 (to Z.Y.). The geodynamics computational work was supported by resources provided by the High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University and the Pawsey Supercomputing Center with funding from the Australian Government. The impact simulations were conducted on the High-Performance Computer at Macau University of Science and Technology, supported by the Macau Science and Technology Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.Z. and M.D. developed the concept and M.-H.Z. framed the work. M.-H.Z. conducted the 3D impact modelling. N.Z. and Haoyuan Li performed the convection experiments. N.Z., M.D. and M.-H.Z. analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. Huacheng Li and Z.Y. joined the initial discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Ian Garrick-Bethell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Simon Harold, Stefan Lachowycz.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

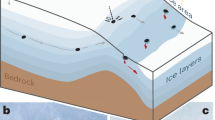

Extended Data Fig. 1 SPA-induced mantle uplift and thermochemical structure.

(a-d) Modeled region with uplifted mantle (grey dots with black boundaries) for four cases with varied impactor size (420 and 315 km) and impact angle (30, 45, and 60°). See Extended Data Table 1 for the labelling scheme of the cases. Bouguer gravity anomaly is shown for comparison, together with the inner (blue ellipse) and outer (red ellipse) rims of the SPA basin28. The plots are presented in Azimuthal projection centred at (169°W, 53.2°S), the center of SPA basin28. (e-h) Corresponding impact-induced temperature anomaly and IBC re-distribution, similar to Fig. 2b. The chemical structures are plotted in the 2D cross section that cut through the SPA center (corresponding to the white dashed great-circle in Fig. 1c) with greenish IBC materials. The thermal structures are plotted as 3D contours of the 1,800 °C isotherm (red contours). The SPA spatial extent is marked by grey double-headed arrows (e-h).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Final evolution states of modeled thermochemical structures.

The final state is reached after the disappearance of pushing effect of impact-induced hot anomalies at ~ 300 Myr (a-g) and ~ 200 Myr (h) after the impact. Similar to Fig. 2f but for different test cases: (a) I420_deg60_v-2D50 (that is, the reference case, same with Fig. 2f); (b) I315_deg60_v-2D50; (c) I420_deg45_v-2D50; (d) I420_deg30_v-2D50; (e) I420_deg60_v-3D50; (f) I420_deg60_v-1D50; (g) v-2D50 (the base case without the SPA impact); (h) I420_deg60_v-2D50_den0 (no IBC density contrast with respect to the surrounding mantle). Mantle flow vectors are included in (h) to demonstrate that the impact-induced hot anomalies cannot maintain the global degree-one convection without the assistance of mantle overturn.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Modelled final distribution of the IBC thickness.

Similar to Fig. 1c but without vertical integration. The cases shown for comparison are the same with those in Extended Data Fig. 3: (a) I420_deg60_v-2D50 (that is, the reference case); (b) I315_deg60_v-2D50; (c) I420_deg45_v-2D50; (d) I420_deg30_v-2D50; (e) I420_deg60_v-3D50; (f) I420_deg60_v-1D50; (g) v-2D50 (the base case without the SPA impact); (h) I420_deg60_v-2D50_den0 (no IBC density contrast with respect to the surrounding mantle). The last two cases (using a different colour bar from other cases) demonstrate that neither the impact-induced hot anomalies nor the IBC gravitational instability alone can lead to a hemispherical azimuthal migration of IBC. The plots are presented in the Mollweide equal‐area projection centred at 90°W longitude, with the nearside on the right side of the map and the farside on the left side.

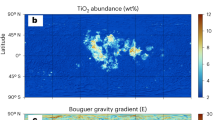

Extended Data Fig. 4 Comparison between observed and modelled degree-one TiO2 distribution.

Degree-one component of (a) observed TiO2 distribution (corresponding to Fig. 1a) and (b) modeled TiO2 distribution for the reference case (corresponding to Fig. 1c). Mare boundaries and the SPA boundary are shown by black contours and white curve, respectively. Data are presented in a Mollweide equal‐area projection centred at 90°W longitude, with the nearside on the right side of the map and the farside on the left side.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

Modelled SPA-induced thermodynamic evolution. The impactor strikes the Moon from the top of this cross-section at an impact angle of 60°. This cross-section is the same as in Fig. 2, but rotated by 180° and horizontally flipped. Ejecta at locations distant from the SPA basin are numerical artefacts caused by a limited resolution of the simulation. This video is for the reference case and lasts for 8 h.

Supplementary Video 2

Modelled post-impact thermochemical evolution with mantle overturn. Top: evolution of thermochemical structure with red 3D contours representing the 1,800 °C isotherm and green colour representing the IBC fraction, similar to Fig. 2. Bottom: corresponding evolution of the IBC thickness, similar to Extended Data Fig. 4. The video is generated for the reference case and lasts for 270 Myr.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for the modeled TiO2 and Th content of our reference model in Fig. 1c,d.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2 (that is, our reference case). It is 3D ASCII data compressed by the software 7-zip.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for the compositional evolution of our reference model in Fig. 3a, and source data for the IBC shape in Fig. 3b.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Modeled tracer points with mantle uplift from iSALE-3D models in Extended Data Fig. 1. Locations of these points (currently centred at 52° S, 180° E) should be shifted and rotated to be consistent with the location of SPA.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Source data for plotting Extended Data Fig. 2b-h. The data source for Extended Data Fig. 2a is the same as that for Fig. 2. It is 3D ASCII data compressed by the software 7-zip.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Modeled IBC distribution from CitcomS shown in Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Source data for degree-1 components of the observed and modeled TiO2 content in Extended Data Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, N., Ding, M., Zhu, MH. et al. Lunar compositional asymmetry explained by mantle overturn following the South Pole–Aitken impact. Nat. Geosci. 15, 37–41 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00872-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00872-4

This article is cited by

-

Don’t judge the Moon’s interior by its cover

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

Titanium-rich basaltic melts on the Moon modulated by reactive flow processes

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

Vestiges of a lunar ilmenite layer following mantle overturn revealed by gravity data

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

An overview and perspective of identifying lunar craters

Science China Earth Sciences (2024)

-

Thorium anomaly on the lunar surface and its indicative meaning

Acta Geochimica (2024)