Abstract

Marine heatwaves (MHWs) are periods of extreme warm sea surface temperature that persist for days to months1 and can extend up to thousands of kilometres2. Some of the recently observed marine heatwaves revealed the high vulnerability of marine ecosystems3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11 and fisheries12,13,14 to such extreme climate events. Yet our knowledge about past occurrences15 and the future progression of MHWs is very limited. Here we use satellite observations and a suite of Earth system model simulations to show that MHWs have already become longer-lasting and more frequent, extensive and intense in the past few decades, and that this trend will accelerate under further global warming. Between 1982 and 2016, we detect a doubling in the number of MHW days, and this number is projected to further increase on average by a factor of 16 for global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to preindustrial levels and by a factor of 23 for global warming of 2.0 degrees Celsius. However, current national policies for the reduction of global carbon emissions are predicted to result in global warming of about 3.5 degrees Celsius by the end of the twenty-first century16, for which models project an average increase in the probability of MHWs by a factor of 41. At this level of warming, MHWs have an average spatial extent that is 21 times bigger than in preindustrial times, last on average 112 days and reach maximum sea surface temperature anomaly intensities of 2.5 degrees Celsius. The largest changes are projected to occur in the western tropical Pacific and Arctic oceans. Today, 87 per cent of MHWs are attributable to human-induced warming, with this ratio increasing to nearly 100 per cent under any global warming scenario exceeding 2 degrees Celsius. Our results suggest that MHWs will become very frequent and extreme under global warming, probably pushing marine organisms and ecosystems to the limits of their resilience and even beyond, which could cause irreversible changes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Scannell, H. A., Pershing, A. J., Alexander, M. A., Thomas, A. C. & Mills, K. E. Frequency of marine heatwaves in the North Atlantic and North Pacific since 1950. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2069–2076 (2016).

Marbà, N. & Duarte, C. M. Mediterranean warming triggers seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) shoot mortality. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2366–2375 (2010).

Wernberg, T. et al. An extreme climatic event alters marine ecosystem structure in a global biodiversity hotspot. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 78–82 (2013).

Di Lorenzo, E. & Mantua, N. Multi-year persistence of the 2014/15 North Pacific marine heatwave. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 1042–1047 (2016).

McCabe, R. M. et al. An unprecedented coastwide toxic algal bloom linked to anomalous ocean conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 10,366–10,376 (2016).

Cavole, L. et al. Biological impacts of the 2013–2015 warm-water anomaly in the Northeast Pacific: winners, losers, and the future. Oceanography 29, 273–285 (2016).

Wernberg, T. et al. Climate-driven regime shift of a temperate marine ecosystem. Science 353, 169–172 (2016).

Hughes, T. P. et al. Global warming and recurrent mass bleaching of corals. Nature 543, 373–377 (2017).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. The unprecedented 2015/16 Tasman Sea marine heatwave. Nat. Commun. 8, 16101 (2017).

Garrabou, J. et al. Mass mortality in Northwestern Mediterranean rocky benthic communities: effects of the 2003 heat wave. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1090–1103 (2009).

Mills, K. E. et al. Fisheries management in a changing climate: lessons form the 2012 ocean heat wave in the Northwest Atlantic. Oceanography 26, 191–195 (2014).

Caputi, N. et al. Management adaptation of invertebrate fisheries to an extreme marine heat wave event at a global warming hot spot. Ecol. Evol. 6, 3583–3593 (2016).

Pershing, A. J. et al. Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery. Science 350, 809–812 (2015).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. 9, 1324 (2018).

Climate Action Tracker. Improvement in warming outlook as India and China move ahead, but Paris Agreement gap still looms large (2017); https://climateactiontracker.org/documents/61/CAT_2017-11-15_ImprovementInWarmingOutlook_BriefingPaper.pdf.

Pachauri, R. K. & Meyer, L. A. (eds.) Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, Geneva, 2014).

Walsh, J. E. et al. The high latitude marine heat wave of 2016 and its impacts on Alaska. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 39–43 (2018).

Frölicher, T. L. & Laufkötter, C. Emerging risks from marine heat waves. Nat. Commun. 9, 650 (2018).

Pearce, A. F. & Feng, M. The rise and fall of the ‘marine heat wave’ off Western Australia during the summer of 2010/2011. J. Mar. Syst. 111–112, 139–156 (2013).

Bond, N. A., Cronin, M. F., Freeland, H. & Mantua, N. Causes and impacts of the 2014 warm anomaly in the NE Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 3414–3420 (2015).

Banzon, V., Smith, T. M., Liu, C. & Hankins, W. A long-term record of blended satellite and in situ sea surface temperature for climate monitoring, modeling and environmental studies. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 165–176 (2016).

Morley, J. W., Batt, R. D. & Pinsky, M. L. Marine assemblages respond rapidly to winter climate variability. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2590–2601 (2017).

Frölicher, T. L., Rodgers, K. B., Stock, C. A. & Cheung, W. W. L. Sources of uncertainties in 21st century projections of potential ocean ecosystem stressors. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 30, 1224–1243 (2016).

Carton, J. A., Ding, Y. & Arrigo, K. R. The seasonal cycle of the Arctic Ocean under climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7681–7686 (2015).

Bindoff, N. L. et al. Detection and Attribution of Climate Change: from Global to Regional. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2013).

Comte, L. & Olden, J. D. Climatic vulnerability of the world’s freshwater and marine fishes. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 718–722 (2017).

Logan, C. A., Dunne, J. P., Eakin, C. M. & Donner, S. D. Incorporating adaptive responses into future projections of coral bleaching. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 125–139 (2014).

Donelson, J. M., Munday, P. L., McCormick, M. I. & Pitcher, C. R. Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 30–32 (2012).

Stock, C. A. et al. Reconciling fisheries catch and ocean productivity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E1441–E1449 (2017).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5473–5496 (2007).

Eakin, C. M. et al. Caribbean corals in crisis: record thermal stress, bleaching, and mortality in 2005. PLoS One 5, e13969 (2010).

Stott, P., Stone, D. & Allen, M. Human contribution to the European heatwave of 2003. Nature 432, 610–614 (2004); corrigendum 436, 1200 (2005).

Fischer, E. M. & Knutti, R. Anthropogenic contribution to global occurrence of heavy-precipitation and high-temperature extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 560–564 (2015).

Jacox, M. G., Alexander, M. A., Mantua, N. & Scott, J. D. Forcing of multiyear extreme ocean temperatures that impacted California Current marine resources in 2016. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 27–33 (2018).

Newman, M., Wittenberg, A. T., Cheng, L., Compo, G. P. & Smith, C. A. The extreme 2015/16 El Nino, in the context of historical climate variability and change. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 99, 16–20 (2018).

Allen, M. R. & Ingram, W. J. Constraints on future changes in climate and the hydrologic cycle. Nature 419, 224–232 (2002); corrigendum 489, 590 (2012).

Angélil, O. et al. Attribution of extreme weather to anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions: Sensitivity to spatial and temporal scales. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2150–2155 (2014).

King, A. D. et al. Emergence of heat extremes attributable to anthropogenic influences. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3438–3443 (2016).

Frölicher, T. L. & Paynter, D. J. Extending the relationship between global warming and cumulative carbon emissions to multi-millennial timescales. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 075002 (2015).

Fay, A. R. & McKinley, G. A. Global ocean biomes: mean and temporal variability. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 7, 107–128 (2014).

Acknowledgements

T.L.F. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant PP00P2_170687 and N.G. under grant XEBUS 200020_175787. E.M.F and N.G. acknowledge support from ETH Zürich. This work is part of the Nippon Foundation Nereus Program, a collaborative initiative by the Nippon Foundation and partners, including ETH Zürich. We thank the World Climate Research Programme’s Working Group on Coupled Modelling, which is responsible for CMIP5, and the climate modelling groups (listed in Methods) for producing and making available their model output. We thank T. Stocker, F. Joos and C. Raible for discussions, U. Beyerle for downloading most of the CMIP5 data, and D. Kessler and M. Aschwanden for their initial analyses. The maps in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Figs. 1– 3 were created using the NCAR Command Language (https://www.ncl.ucar.edu).

Reviewer information

Nature thanks R. Asch, E. Oliver and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors designed the study. T.L.F. performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript together with N.G., with substantial input from E.M.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Observed and simulated MHW characteristics exceeding the 1982–2016 99th percentile, averaged over the 1982–2016 period.

a, b, Differences between the 99th percentile in SST and the annual mean SST. c, d, Annual mean duration of MHWs. e, f, Maximum annual intensity of MHWs. g, h, Annual cumulative mean intensity of MHWs. Satellite-derived patterns (a, c, e, g) and CMIP5 multi-model mean patterns (b, d, f, h). The black contours in all panels highlight the pattern structures. The spatial correlation between the CMIP5 multi-model mean and the satellite-based estimates is r2 = 0.80 for a and b, r2 = 0.15 for c and d, r2 = 0.43 for e and f, and r2 = 0.18 for g and h.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Spatial extent of observed and simulated MHWs over the satellite data taking period.

a, Histogram of the spatial extent of satellite-observed MHWs above the climatological (1982–2016) 99th percentile for the 1982–1998 (blue) and 1999–2016 (red) period. b, The spatial pattern of the MHW with the largest extent in the satellite data taking period (1982–2016), which occurred on 2 September 2015 in the North Pacific and was associated with the ‘the Blob’21. It had a spatial extent of about twice the area of the United States (that is, 1.85 × 107 km2). Shown are SST anomalies above the 1982–2016 climatological 99th percentile on 2 September 2015. The colour bar shows degrees Celsius. c, Comparison between satellite-based observations (black line) and simulations (red histogram) of the spatial extent of MHWs above the climatological 99th percentile over the 1982–2016 period. The number of MHWs (y axis) is normalized with the total number of MHWs. Deeper red colour indicates a greater number of overlapping models.

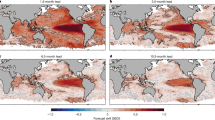

Extended Data Fig. 3 Simulated multi-model mean changes in different MHW characteristics exceeding the preindustrial 99th percentile since preindustrial times for different global warming levels.

a–l, Changes in the maximum annual intensity (a, d, g, j), annual mean duration (b, e, h, k) and annual cumulative mean intensity (c, f, i, l) of MHWs for global warming of 1 °C (a–c), 1.5 °C (d–f), 2 °C (g–i) and 3.5 °C (j–l). The black contours highlight the pattern of changes.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Simulated changes in different MHW characteristics exceeding the preindustrial 99th percentile.

The data were obtained from a 10-member ensemble simulation with NCAR-DOE CESM34. a–d, The probability ratio (a), annual mean duration (b), maximum annual intensity (c) and annual cumulative mean intensity (d) of MHWs. The black lines show the individual ensemble members. The red line in a shows the probability ratio versus global warming for a reference period that is defined as the 99th percentile over the 2007–2026 period, obtained using all ten ensemble members. The ensemble members are initialized from different starting points (ocean, sea ice, land and atmosphere) in the preindustrial control simulation. The simulations follow the RCP 8.5 scenario over the 21st century. The time series are smoothed with a 20-year running mean.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Simulated changes in MHW characteristics for different global warming levels and different extreme thresholds.

a, c–e, Global annual mean probability ratio (a; logarithmic scale), duration (c), maximum intensity (d) and cumulative mean intensity (e) of MHWs versus different extreme thresholds for different changes in global mean surface air temperature. b, Changes in the ratio of the mean spatial extent of MHWs between global warming conditions and 1861–1880 conditions. Simulations following only the RCP 8.5 scenario are shown. The shaded areas indicate the maximum range simulated by the CMIP5 models.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison between simulated changes in MHW characteristics exceeding the 99th percentile from a natural-forcing simulation and from a preindustrial control simulation using GFDL ESM2M forced with the RCP 8.5 scenario over the 21st century.

a–d, The probability ratio (a), annual mean duration (b), maximum annual intensity (c) and annual cumulative mean intensity (d) of MHWs. The red line shows the simulated changes exceeding the 99th percentile from a natural-forcing simulation of GFDL ESM2M forced with observed solar and volcanic boundary conditions, but with greenhouse gases and aerosol concentrations set to preindustrial. The black line shows the simulated changes exceeding the preindustrial 99th percentile. The time series are smoothed with a 20-year running mean.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Simulated changes in global SST as a function of global surface air temperature over land.

The light red and blue lines represent individual model projections, whereas the dark red and blue lines represent multi-model averages for the RCP 8.5 (red) and RCP 2.6 (blue) scenarios. The time series are smoothed with a 20-year running mean. The grey dashed 1:1 line is shown for reference.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frölicher, T.L., Fischer, E.M. & Gruber, N. Marine heatwaves under global warming. Nature 560, 360–364 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0383-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0383-9

This article is cited by

-

Quantifying coastal freshwater extremes during unprecedented rainfall using long timeseries multi-platform salinity observations

Nature Communications (2024)

-

A marine heatwave drives significant shifts in pelagic microbiology

Communications Biology (2024)

-

Marine protected areas promote stability of reef fish communities under climate warming

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Global increase in tropical cyclone ocean surface waves

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Summer heatwaves on the Baltic Sea seabed contribute to oxygen deficiency in shallow areas

Communications Earth & Environment (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.