Abstract

In the debate on biobank regulation, arguments often draw upon findings in surveys on public attitudes. However, surveys on willingness to participate in research may not always predict actual participation rates. We compared hypothetical willingness as estimated in 11 surveys conducted in Sweden, Iceland, United Kingdom, Ireland, United States and Singapore to factual participation rates in 12 biobank studies. Studies were matched by country and approximate time frame. Of 22 pairwise comparisons, 12 suggest that factual willingness to participate in biobank research is greater than hypothetical, six indicate the converse relationship, and four are inconclusive. Factual donors, in particular when recruited in health care or otherwise face-to-face with the researcher, are possibly motivated by factors that are less influential in a hypothetical context, such as altruism, trust, and sense of duty. The value of surveys in assessing factual willingness may thus be limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Successful biobank research depends on people's attitudes and trust in science.1, 2, 3 Unsurprisingly, arguments for various regulative practices often rely on survey assessments of such attitudes.4, 5 A well-known limitation of surveys, however, is that in matters of low salience to the responders, their actions may contradict their stated intentions.6 Factual participation in biobank research has sometimes been much greater than predicted.7 In this study, we hypothesize that this is a general tendency rather than an isolated phenomenon.

Materials and methods

By tracking references from contemporary literature on public attitudes to biobank research, we identified nine public attitude surveys from Sweden,2, 8 Iceland,9 the United Kingdom,10 Ireland,11 the United States,12, 13, 14 and Singapore15 addressing willingness to participate in biobank research or to store samples for future research. As sample donors are often recruited in health care, we also included two British surveys conducted on patients.16, 17 Surveys carried out on previous research subjects or sub-populations could not be expected to be representative of the general population and were thus excluded.

Several published biobank studies carried out in the United Kingdom,18, 19 United States,20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Iceland,25 and Singapore26, 27 had data on factual participation rates. In Sweden, we obtained participation data from a biobank maintained by the department of Endocrine Oncology, Uppsala University Hospital. The Trinity Biobank in Dublin provided us with Irish recruitment data. All included studies used opt-in for enrollment.

We endeavored to match each survey to one or several biobank research projects carried out in the same country in approximately the same time frame. Owing to the small number of studies we accepted a five-year gap (mid-enrollment).

Statistical analysis

Survey estimates of hypothetical willingness were compared with factual participation rates using the χ2-test with continuity correction and α=0.05. Some studies did not report raw numbers; in these cases, ranges of possible numerators and denominators were reverse-engineered from percentages and n-values. Those ratios least likely to reject the null hypothesis were selected for analysis. In cases where subjects were recruited to a real-world study from a population of previous responders, we used the cumulative participation rate for comparisons to eliminate selection bias. P-values less than 0.0001 are reported as <0.0001; others are presented as exact values.

Results

The willingness of Swedes to donate samples for genetic research and long-term storage was estimated to 78% in 2002 (Table 1).2 According to another survey from 2003, 94% would agree or consider agreeing to storage of traceable samples for future research if allowed to choose between various models of consent ranging from renewed consent for each purpose to blanket consent.8 Of 307 unique patients admitted to the department of Endocrine Oncology in Uppsala in July–December 2003, 233 correctly filled out at least one consent/refusal form. Of the latter, 98% consented to research and open-ended storage, which is more than predicted by the surveys.

According to an Icelandic public survey (ELSAGEN) conducted in 2002, 65% thought they would be very or rather likely to participate in genetic research in the future.9 Factual recruitment rates in the Icelandic Cancer Project (ICP) during 2001–2002 were higher: 88% of eligible patients and 82% of controls agreed to open-ended storage of samples for use in other cancer research projects, including genetic and commercial research.25

In 2002, the willingness to join the UK Biobank was estimated to 34%.10 Such participation implies consent to open-ended storage and genetic research. A survey on British dental patients in 2003 found that 82% would donate excess tissue to cancer research if asked.17 In 2005, 96% of postoperative patients in a teaching hospital thought that they would not object to their tissue being used in research.16 Participation in a biobank study from 1998 to 2002 was higher than predicted by any of the three surveys, with 99% of surgical patients donating leftover tissue to commercial biomedical research.18 In the UK Biobank pilot phase in 2006, invitations were sent by mail to a random sample of the population in the vicinity of an assessment center. Of those contacted in February–April, 10% agreed,19 which is lower than predicted by the reviewed surveys.

In 2004, 74% of the Irish claimed to be willing to donate excess tissue for non-genetic research and storage for future research.11 In the same year, Trinity Biobank recruited subjects by posting buccal swab kits to a random sample of the population (Joe McPartlin, personal communication). The participants gave broad consent for use of their samples, including genetic research and open-ended anonymized storage. The participation rate was 17%, which is far less than estimated by the survey.

Of participants in the 1998 American Healthstyles Survey, 43% thought themselves willing to donate samples for genetic research and storage for future research; 53% would consent to genetic research but not to storage.13 Another American survey from 2005 found that of those respondents who could be segmented into categories depending on their attitudes to genetic research, 46% were either ‘supportive’ or ‘altruistic’.12 A third survey conducted in 2007–2008 estimated the willingness of Americans to participate in a cohort study involving genetic research to 60%.14 We matched these studies to five American biobank studies. Of Americans eligible for the 1999 NHANES survey, 60% (84% of respondents) donated samples to be stored for future academic biomedical research, including genetic research.23 In another study conducted in 1999–2000, a random sample of the population was interviewed by phone about their smoking behavior and asked to mail buccal swabs for genetic analysis. Participation among interviewees was 26%.20 A large-scale population-based biobank had a 44% enrollment rate in 2002–2004.21 In a study on colorectal cancer patients in 2001–2004, 63% donated samples to genetic research.24 In 2003–2004, samples collected from NHANES respondents were no longer used for genetic research or stored for future research; under these conditions, 71% of eligible Americans (98% of respondents) donated samples.22 Of the resulting ten comparisons, five indicate that actual participation was higher than predicted, two suggest the converse relationship, and three show no difference.

An interview study on the general population in Singapore in 2002 estimated the willingness to donate blood for genetic research and storage for future research to 40%.15 In the Singapore Prospective Study Program (SP2), the recruitment rate in 2004–2007 was 64%. Participants were recruited from the 199226 and 199827 Singapore National Health Surveys; adjusting for the 68% response rate of these surveys yields a cumulative response rate of 43%, which is comparable with the survey estimate.

Discussion

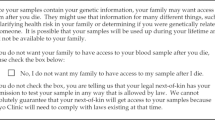

Of 22 pairwise comparisons, 12 suggest that factual willingness to participate in biobank research is greater than surveys predict, six indicate the converse relationship, and four show no difference (Figure 1). Owing to the small number of studies included, we could not control for some potentially influential confounders, nor is it possible to analyze them statistically. We will, however, give a rough indication of the extent to which they may have affected our results.

Willingness to participate in biobank research. In 12 of 22 pairwise comparisons, factual willingness to participate in biobank research was higher than estimated in the corresponding surveys. Six comparisons yielded the opposite result. In two of these (IE and US2), the biobank studies recruited participants by asking them to supply buccal swabs by mail. In three others (GB4, GB5, and GB6) the first stage of recruitment to the biobank study in question (UK Biobank) relied on potential subjects to respond to a mailed invitation, which could explain part of the dropout. Significant differences (P<0.05) are marked by an asterisk. Each comparison has an index that identifies the study country (SE=Sweden, IS=Iceland, GB=Great Britain, IE=Ireland, US=United States, SG=Singapore). For details on the studies in each pair, see Table 1.

Some studies suggest that fewer people are willing to donate material for research and open-ended storage than for research alone.2, 13, 15, 17 Involvement of commercial interests has been identified as another deterring factor in some contexts.3, 4, 28, 29 However, these two factors explain nothing of our findings (Table 2).

Some people may associate genetic research with eugenics or discrimination3, 29 or think of it as ‘tampering with nature.’11, 28 It is at least possible that genetic research could have been a deterring factor in seven cases, though other factors may partly explain these differences.

Patients may be more inclined to participate in research than the general public,11 possibly from a sense of duty to reciprocate30 or because they find themselves part of a social agreement,16 community, or alliance.31 Potential research subjects may find it easier to trust researchers whom they meet face-to-face, and so may be more likely to agree to participate. These two factors together may have influenced the outcomes of twelve comparisons. They may not always be crucial, however: In the Icelandic Cancer Project, controls were recruited by phone and mail, but participation in this group was almost as high as among patients, with whom the researcher had face-to-face contact at some point.25

The above factors do not, in isolation or jointly, explain all of our results. We argue that this residue can be explained by reference to fundamental differences between hypothetical and factual choice. Psychologists have found that the more highly embedded an attitude, the more strongly it is related to behavioral intentions.32 If a survey fails to engage the subject, it may reflect mere opinions rather than stable attitudes.6 In contrast, finding that one's choice really matters could awaken a fuller range of emotional rationality.

Our study has some important limitations. Some biobank studies relied on invitees to respond to mailed invitations (UK Biobank and Trinity Biobank), possibly yielding dropout that does not reflect unwillingness to participate as such. As we have expressed participation rates as percentages of all invitees, actual willingness may have been underestimated in these cases. Willingness to participate in research may also be context-sensitive in ways that escape the above categorization; for instance, people's views regarding a specific biobank do not necessarily reflect their attitudes toward biobank research as a whole.

Public surveys are expected to provide accurate estimates of people's attitudes and to be representative of the population. Those that we reviewed in this study predicted behavior poorly, which could be due to either individual flaws or a general tendency to reflect attitudes other than those that are operative in actual decisions to participate in research. Both possible sources of error must be held in mind when surveys assessing willingness to participate in research are used in policy making.

References

Hansson MG : Ethics and biobanks. Br J Cancer 2009; 100: 8–12.

Kettis-Lindblad A, Ring L, Viberth E, Hansson MG : Genetic research and donation of tissue samples to biobanks. What do potential sample donors in the Swedish general public think? Eur J Public Health 2006; 16: 433–440.

Levitt M, Weldon S : A well placed trust?: Public perceptions of the governance of DNA databases. Crit Public Health 2005; 15: 311–321.

Caulfield T : Biobanks and Blanket Consent: the proper place of the public good and public perception rationales. King's Law Journal 2007; 18: 209–226.

Wendler D : One-time general consent for research on biological samples. Br Med J 2006; 332: 544–547.

Pardo R, Midden C, Miller JD : Attitudes toward biotechnology in the European Union. J Biotechnol 2002; 98: 9–24.

Johnsson L, Hansson MG, Eriksson S, Helgesson G : Patients' refusal to consent to storage and use of samples in Swedish biobanks: cross sectional study. Br Med J 2008; 337: a345.

Nilstun T, Hermeren G : Human tissue samples and ethics--attitudes of the general public in Sweden to biobank research. Med Health Care Philos 2006; 9: 81–86.

Gu∂mundsdóttir ML, Nordal S Iceland; in: Häyry M, Chadwick R, Árnason V, Árnason G (eds): The Ethics and Governance of Human Genetic Databases: European Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Hapgood R, McCabe C, Shickle D : Public Preferences for Participation in a Large DNA Cohort Study: A Discrete Choice Experiment: Sheffield Health Economics Group Discussion Paper Series. Sheffield: The University of Sheffield, School of Health and Related Research, 2004.

Cousins G, McGee H, Ring L et al: Public Perceptions of Biomedical Research: A Survey of the General Population in Ireland. Dublin: Health Research Board, 2005.

Pulley JM, Brace MM, Bernard GR, Masys DR : Attitudes and perceptions of patients towards methods of establishing a DNA biobank. Cell Tissue Bank 2008; 9: 55–65.

Wang SS, Fridinger F, Sheedy KM, Khoury MJ : Public attitudes regarding the donation and storage of blood specimens for genetic research. Community Genet 2001; 4: 18–26.

Kaufman D, Murphy J, Scott J, Hudson K : Subjects matter: a survey of public opinions about a large genetic cohort study. Genet Med 2008; 10: 831–839.

Wong ML, Chia KS, Yam WM, Teodoro GR, Lau KW : Willingness to donate blood samples for genetic research: a survey from a community in Singapore. Clin Genet 2004; 65: 45–51.

Bryant RJ, Harrison RF, Start RD et al: Ownership and uses of human tissue: what are the opinions of surgical in-patients? J Clin Pathol 2008; 61: 322–326.

Goodson ML, Vernon BG : A study of public opinion on the use of tissue samples from living subjects for clinical research. J Clin Pathol 2004; 57: 135–138.

Jack AL, Womack C : Why surgical patients do not donate tissue for commercial research: review of records. Br Med J 2003; 327: 262.

UK Biobank. Report of the Integrated Pilot Phase. Stockport: UK Biobank Coordinating Centre, 2006.

Kozlowski LT, Vogler GP, Vandenbergh DJ, Strasser AA, O'Connor RJ, Yost BA : Using a telephone survey to acquire genetic and behavioral data related to cigarette smoking in ‘made-anonymous’ and ‘registry’ samples. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 156: 68–77.

McCarty CA, Wilke RA, Giampietro PF, Wesbrook SD, Caldwell MD : Marshfield Clinic Personalized Medicine Research Project (PMRP): design, methods and recruitment for a large population-based biobank. Personalized Med 2005; 2: 49–79.

McQuillan GM, Pan Q, Porter KS : Consent for genetic research in a general population: an update on the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey experience. Genet Med 2006; 8: 354–360.

McQuillan GM, Porter KS, Agelli M, Kington R : Consent for genetic research in a general population: the NHANES experience. Genet Med 2003; 5: 35–42.

Ford BM, Evans JS, Stoffel EM, Balmana J, Regan MM, Syngal S : Factors associated with enrollment in cancer genetics research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15: 1355–1359.

Rafnar T, Thorlacius S, Steingrimsson E et al: The Icelandic Cancer Project—a population-wide approach to studying cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2004; 4: 488–492.

Tan CE, Emmanuel SC, Tan BY, Jacob E : Prevalence of diabetes and ethnic differences in cardiovascular risk factors. The 1992 Singapore National Health Survey. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 241–247.

Cutter J, Tan BY, Chew SK : Levels of cardiovascular disease risk factors in Singapore following a national intervention programme. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79: 908–915.

Human Genetics Commission: Public Attitudes to Human Genetic Information. London: Human Genetics Commission, 2001.

Wong ML, Chia KS, Wee S et al: Concerns over participation in genetic research among Malay-Muslims, Chinese and Indians in Singapore: a focus group study. Community Genet 2004; 7: 44–54.

Hoeyer K, Lynoe N : Motivating donors to genetic research? Anthropological reasons to rethink the role of informed consent. Med Health Care Philos 2006; 9: 13–23.

Dixon-Woods M, Wilson D, Jackson C, Cavers D, Pritchard-Jones K : Human Tissue and ‘the Public’: the case of childhood cancer tumour banking. BioSocieties 2008; 3: 57–80.

Ajzen I : Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol 2001; 52: 27–58.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the AutoCure and CCPRB projects of the EU Sixth Framework Programme. The authors of this study have been independent from the funders in both conception and execution of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Author contributions

LJ, GH, SE, and MGH designed the study. LJ, TR, IH, and CKS collected the data. LJ analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors contributed to revision of critical intellectual content and approved the publication of the final version of this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnsson, L., Helgesson, G., Rafnar, T. et al. Hypothetical and factual willingness to participate in biobank research. Eur J Hum Genet 18, 1261–1264 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.106

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2010.106

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Get this thing out of my body! Factors determining consent for translational oncology research: a qualitative research

Journal of Translational Medicine (2023)

-

Public’s awareness of biobanks and willingness to participate in biobanking: the moderating role of social value orientation

Journal of Community Genetics (2023)

-

History of the largest global biobanks, ethical challenges, registration, and biological samples ownership

Journal of Public Health (2023)

-

Donation of discarded ocular tissue in patients undergoing SMILE laser refractive surgery: developing appropriate guidelines

Cell and Tissue Banking (2020)

-

Questioning the rhetoric of a ‘willing population’ in Finnish biobanking

Life Sciences, Society and Policy (2019)