Abstract

Purpose

Vitiligo iridis refers to focal areas of iris atrophy as sequelae of small pox infection. We report a series of patients with unilateral vitiligo iridis, some of whom presented with secondary open-angle glaucoma.

Methods

Three patients with vitiligo iridis underwent a comprehensive ophthalmic examination including intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement, slit lamp biomicroscopy, gonioscopy, and fundus evaluation. Patients’ facial features were also documented and photographed.

Results

All patients were in their sixth decade. Two out the three had elevated IOP (52 mm Hg and 36 mm Hg) in the same eye as vitiligo iridis, at initial presentation. Gonioscopy showed patchy iris hyperpigmentation and fundus evaluation showed glaucomatous optic disc changes in the involved eye. One patient responded favourably to topical antiglaucoma medications, whereas the other was taken up for combined phacoemulsification–trabeculectomy with good results. The third patient had normal IOP in the involved eye. All three patients gave a history of small pox in childhood and had pitted facial scars typical of previous small pox infection.

Conclusions

Vitiligo iridis may be associated with the secondary glaucoma as a long-term sequelae of small pox. It may be prudent to periodically follow-up such patients for development of raised IOP in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Focal areas of iris atrophy, termed vitiligo iridis, has been previously reported as a late complication in up to 50% of patients with small pox.1, 2, 3, 4 However, it has not been associated with any vision-threatening diseases in the past. We report a series of patients with unilateral vitiligo iridis with secondary glaucoma in the same eye with past history of small pox in childhood.

Case 1

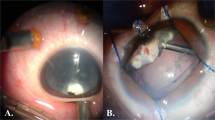

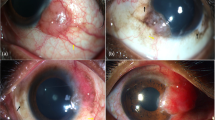

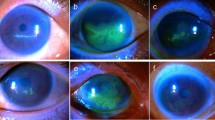

A 60-year-old man, presented with painless progressively decrease in vision in his right eye. He had best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 6/6 with constricted field of vision. Slit lamp evaluation of the right eye revealed multiple greyish-white circular spots on the anterior surface of the iris, termed vitiligo iridis (Figure 1a). A relative afferent pupillary defect was present with intraocular pressure (IOP) of 52 mm Hg and cup–disc ratio of 0.8 (Figure 1b). Gonioscopy showed open angles with patchy hyperpigmention of the trabecular meshwork in all the quadrants (Figure 1c). The left eye had BCVA of 6/6 and was unremarkable with no evidence of glaucoma. The IOP was controlled with topical antiglaucoma medications.

Case 2

A 62-year-old man, presented with painless progressively decrease in vision in his right eye. He had BCVA of 6/12. Anterior segment examination showed vitiligo iridis (Figure 2a) and nuclear sclerosis with posterior subcapsular cataract. The other anterior segment structures were normal. The IOP was 36 mm Hg. Fundus showed cup disc ratio of 0.85 with concentric thinning of the neuroretinal rim (Figure 2b). Gonioscopy showed open angles with patchy hyperpigmention of the trabecular meshwork in all the quadrants. Left eye had 6/6 BCVA and was unremarkable with no evidence of glaucoma. Patient was treated with combined phacoemulsification–trabeculectomy procedure in right eye following which IOP was controlled without any antiglaucoma medications.

Case 3

A 60-year-old woman presented to us for routine eye examination. Both eyes were pseudophakic with BCVA 6/6 and normal fundus. The right eye revealed vitiligo iridis on slit lamp evaluation (Figure 3a) while the left eye was normal. The IOP was normal in both the eyes.

Pitted scars (Figures 1d, 2c, and 3b) were seen on the faces of all the three patients and all gave a history of small pox in their childhood. None of our patients had a history or signs of herpetic eye disease, or of previous eye trauma or other forms of eye surgery, except uncomplicated phacoemulsification.

Discussion

As recently as 1967, WHO estimated that 15 million people contracted small pox and that two million died in that year (WHO Smallpox Factsheet; http://www.who.int/csr/disease/smallpox/en/; last accessed on 15 August 2014)). Although small pox was eradicated way back in December 1979, a large number of people infected before 1980 are still surviving and may approach hospitals for age-related eye disorders. Previously, Shukla et al reported two cases of unilateral vitiligo iridis with small pox as the probably aetiological factor.2 Similarly, Rathinam et al reported seven patients with multifocal vitiligo iridis, with both unilateral and bilateral presentation, following past history of small pox infection.3 We report three cases of unilateral vitiligo iridis out of which two cases presented with secondary glaucoma in the same eye.

The probable mechanism for secondary open-angle glaucoma could be small pox virus-induced trabecular damage with reduced residual function, which may have lead to raised IOP later in life. The patchy hyperpigmentation on gonioscopy suggests that the raised IOP could be a variant of pigmentary glaucoma. Coexistent primary open-angle glaucoma is improbable in view of the glaucoma being unilateral; and coexistent vitiligo iridis makes trabecular insult during small pox more likely.

We believe that this is the first report demonstrating the association between open-angle glaucoma and vitiligo iridis as a long-term complication of remote small pox infection. Hence, it may be prudent to periodically follow-up subjects with vitiligo iridis and small pox to determine the incidence of secondary glaucoma in these eyes.

References

Russo A . Alterazioni post-vaiuolose dell’iride. Ann Ottal Clin Ocul 1933; 61: 923–946.

Rathinam SR, Cunningham ET . Vitiligo iridis in patients with a history of smallpox infection. Eye 2010; 24: 1621–1622.

Shukla B, Srivastava SP, Jain SC . Unilateral vitiligo iridis. Br J Ophthalmol 1966; 50: 436–437.

Semba RD . The ocular complications of smallpox and smallpox immunization. Arch Ophthalmol 2003; 121: 715–719.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kavitha, S., Patel, S., Mohini, P. et al. Vitiligo iridis and glaucoma: a rare sequelae of small pox. Eye 29, 1392–1394 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.42

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.42