Abstract

Aims

To report the clinical phenotype in a series of four children from three families with the rare association of high myopia, central macular atrophy, and normal full-field electroretinography (ERG).

Methods

Four male patients were ascertained with reduced vision, nystagmus, and atrophy of the macula from early childhood. Patients underwent full ophthalmic examination, electrophysiological testing, and retinal imaging.

Results

Minimum duration of follow-up was 8 years. At last review, visual acuity ranged from 0.22 to 1.20 logMAR (6/9.5–6/95 Snellen) at a mean age of 10.5 years (median 9.5 years, range 9–14 years). Refractive error ranged from a spherical equivalent of −7.40 D to −24.00 D. Three had convergent squint. Fundus examination and imaging demonstrated bilateral macular atrophy in all patients that varied from mild atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) to well-demarcated, punched-out atrophic lesions of retina, RPE, and choroid. Flash ERG was normal under photopic and scotopic conditions in all patients. Pattern ERG, performed in three patients, was consistent with mild to severe macular dysfunction. Progression of the area of atrophy was evident in one patient and of the myopia in two patients but all patients had stable visual acuity.

Conclusions

Patients with congenital high myopia and macular atrophy present in infancy with reduced visual acuity and nystagmus. The macular atrophic lesions vary in size and severity but electrophysiological testing is consistent with dysfunction confined to the macula. There was no deterioration in visual acuity over 8–10 years of monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A disorder of high myopia with central chorioretinal dystrophy was first described in 1998 in a single family in Jerusalem with 6 of 12 children affected.1 All had reduced visual acuity, and a normal flash electroretinogram (ERG). The youngest age at diagnosis was 7 months. There have been no subsequent reports to date. Although several inherited and acquired conditions can result in atrophic lesions of the macula, this disorder has distinct characteristics: early onset, high myopia, a normal full-field electroretinography, and a lack of other ocular or systemic associations.

The present report details a series of patients presenting in early childhood with high myopia and macular atrophy, all of whom had a normal flash ERG, and describes the detailed phenotype and natural history.

Materials and methods

The study protocol adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the local ethics committee. Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in this study with parental written consent provided on behalf of the children involved in this study.

Four patients from three families including two brothers (patients 2 and 3) were ascertained from the pediatric ophthalmology clinics at Moorfields Eye Hospital and Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK. All patients underwent a full clinical examination including visual acuity and dilated fundus examination. Retinal fundus imaging was obtained by conventional 35° fundus colour photographs (Topcon Great Britain Ltd, Berkshire, UK). Dilated 30 or 55° fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging was performed in two patients and spectral domain OCT imaging (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering Ltd, Hemel Hempstead, UK) in all four patients. Flash ERGs and pattern ERGs (PERG) were performed using periorbital skin electrodes, according to established pediatric protocols.2, 3, 4, 5

Results

The clinical findings in the four male patients are summarised in Table 1. Patients 2 and 3 are brothers and have an unaffected sister. Patient 4 also has an unaffected sister. There was no reported consanguinity in any family. Patients were reviewed over periods of 8–10 years (mean 9.25 years). Initial presentation was with reduced vision at a mean of 21 months (median 12 months, range 14 weeks to 4 years). First recorded visual acuity was with Cardiff cards in three patients with binocular acuities ranging from 6/38 to 6/120 (logMAR equivalent 1.2–1.3); patient 3 presented at the age of 4 years with right and left visual acuities of 0.60 and 0.90 logMAR (6/24 and 6/48 Snellen), respectively. Visual acuities at last review ranged from 0.22 to 1.20 (6/9.5–6/95 Snellen) at a mean age of 10.5 years (median 9.5 years, range 9–14 years). Visual acuities remained stable in all patients throughout follow-up. One patient had mild manifest horizontal nystagmus (patient 4) and three had manifest latent nystagmus.

All eyes had myopia of >−6.0 dioptres (D) spherical equivalent at last review. The refractive error from initial to last review remained stable in two patients and increased in two patients. The myopia in patient 3 increased from a spherical equivalent of −2.50 D right and −3.25 D left at age 4 years to −7.00 D right and −8.25 D left at age 13 years. There was progression in patient 4 from −11.25 D right and −11.50 D left spherical equivalent at age 14 weeks to −18.00 D right and −17.00 D left at age 10 years. Three of the four patients had esotropia. Three patients underwent occlusion therapy to treat potential strabismic amblyopia without improvement in two cases. The left convergent squint in patient 4 was noted to become alternating post occlusion therapy, and subsequently bilateral medial rectus recession surgery was performed.

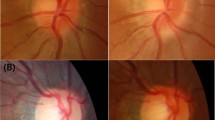

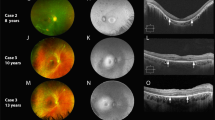

All fundi had a myopic appearance with a thin tessellated retina, with or without tilting of the optic discs, and peripapillary atrophy (Figures 1 and 2). Central macular atrophy of varying degrees was present in all eyes measuring 0.5 disc diameters (both eyes patients 1 and 3), 1 disc diameter (right eye patient 2) and 3 disc diameters (left eye patient 2, both eyes patient 4). Asymmetrical atrophy was noted between eyes of patient 2 and between brothers (patients 2 and 3). There was no apparent correlation between the extent of atrophy and visual acuity. Progression from mild atrophic change less than 0.5 disc diameters in size to full-thickness chorioretinal atrophy 3 disc diameters in size was recorded in patient 4 over a period of 7 years without any corresponding reduction in visual acuity, and with marked changes visible in the first 12 months (Figure 2). FAF imaging (two patients) demonstrated reduced autofluorescence at the site of atrophy with no areas of increased autofluorescence (Figure 1). OCT imaging, performed in all patients, demonstrated variable degrees of loss of outer retina, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), and choroid with lamellar holes in patient 3 and intraretinal small cysts suggestive of retinoschisis in both patients 1 and 3 (Figure 1). In advanced chorioretinal atrophy, staphylomatous change with posterior bowing of the sclera was also present in patients 2 and 4.

Retinal imaging of both eyes of patients 1–3. (a) Colour photographs, (b) optical coherence tomography (OCT), (c) where available, fundus autofluorescence (FAF) imaging. Patient 1 right and left macular atrophy with loss of outer retina, RPE, and choriocapillaris on OCT and reduced autofluorescence on FAF imaging and in addition intraretinal, small cystic change on OCT; patient 2 right mild central atrophy with staphyloma and loss of outer retina, RPE, and choriocapillaris on OCT, left eye punched-out ‘coloboma-like’ lesion with staphyloma and extensive atrophy of retina, RPE, and choroid on OCT; patient 3 right and left peripapillary and central macular atrophy with macular lamellar holes, retinoschisis, and chorioretinal atrophy on OCT and centrally reduced autofluorescence on FAF imaging.

The PERG P50 component to a large stimulus field was reduced bilaterally in three of three patients, in keeping with macular dysfunction, although poor fixation was likely contributory in patient 4 (Figure 3). The PERG in patient 2 was similarly reduced in both eyes despite asymmetrical atrophy. Patient 1 was too young for PERG when tested. Flash ERGs was normal in all cases and revealed no evidence of generalised rod or cone system dysfunction (Figure 3).

Normal flash ERGs from right (R) and left (L) eyes of patients 2, 3, and 4 with representative normal traces for comparison (bottom row). Pattern ERG is subnormal in both eyes of all three patients. Partial eye closure (*) during the photopic flicker ERG recording and poor fixation (**) during PERG testing were noted in patient 4.

Discussion

This study reports a series of children with a rare ocular phenotype characterised by high myopia and nystagmus, variable degrees of central macular atrophy, and normal flash electroretinography.1 Longitudinal assessments over 8–10 years and characterisation of the phenotype using current imaging modalities and electrophysiology confirms that the retinal pathology is both structurally and functionally confined to the macula. The findings suggest a distinct diagnostic entity.

The original description of high myopia with chorioretinal dystrophy was of a single consanguineous family in which 6 of 12 siblings were affected.1 The pedigree was consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance. Both female and male siblings were affected. At presentation, the myopia ranged from −3.00 D to −10.50 D spherical equivalent with variable amounts of atrophy of the choroid and RPE ranging from 2 to 6 disc diameters in size. Although older children generally had larger areas of atrophy and greater levels of myopia, no longitudinal data were presented.1 Our series, in contrast, involves only males but demonstrates a similar phenotype in terms of degree of myopia, atrophic lesions, and normal peripheral retinal function, and also identifies nystagmus as a key feature. The atrophic lesions range from 0.5 to 3 disc diameters and are overall smaller than those previously reported. One child showed progression of macular atrophy in early infancy that later stabilised and was not associated with progressive loss of visual acuity, but in the other patients the retinal changes were stable on long-term follow-up. The term atrophy rather than dystrophy would be more appropriate in this series indicating a developmental rather than a degenerative disorder. Other developmental macular disorders similarly do not show progression with time.6 All patients had reduced vision that did not deteriorate with time. Two of three patients who underwent occlusion therapy for presumed amblyopia showed no improvement in visual acuity most likely due to the underlying structural macular abnormality.

The retinal imaging demonstrated variable degrees of atrophy within the macula on OCT from subtle loss of outer retinal layers to full-thickness coloboma-like lesions. In addition, lamellar holes, retinoschisis, and posterior bowing of the sclera was found. The central macular atrophy in both eyes of patient 3 was unusual in its association with lamellar holes. FAF imaging in two patients showed only reduced central autofluorescence consistent with atrophy without any areas of increased autofluorescence. No patient showed generalised retinal dysfunction on full-field ERG. PERGs were subnormal but clearly present in patients 2 and 3 with reasonably good fixation, suggesting preserved function in areas surrounding the atrophic lesions (Figure 3).

The differential diagnosis in children with infantile-onset macular atrophy includes developmental macular dystrophies, generalised inherited retinal dystrophies, and infectious/inflammatory disorders such as toxoplasmosis. The lack of family history, fundus features, and electrophysiology allow exclusion of these other diagnoses.

Infantile-onset macular atrophy with full-thickness loss of retina, RPE, and choroid can occur in some forms of Leber congenital amaurosis, particularly those caused by mutations in AIPL1, RDH12, and NMNAT1, but full-field ERGs in such patients would be expected to be severely abnormal or undetectable.7, 8, 9

Congenital macular atrophy is also a feature of North Carolina macular dystrophy and other related phenotypes; each of these show dominant inheritance and can thus easily be distinguished.6 North Carolina macular dystrophy can be further differentiated by the presence of drusen-like deposits in the macula and the hyperpigmentation that is associated with the atrophy. Progressive bifocal chorioretinal atrophy, an autosomal dominant disorder of infantile onset, can be distinguished by the presence of nasal subretinal deposits and progressively enlarging atrophy of the macula and nasal retina to a much greater extent than found in this series. Central areolar choroidal dystrophy is another rare autosomal dominant disorder in which RPE changes in the macula progress to atrophy, but with later presentation in the second decade.10

Macular atrophy can also occur in systemic disorders such as Down syndrome.11, 12, 13 A rare syndrome of atypical macular ‘coloboma’ with high myopia and infantile hypercalciuria has been reported in four patients.12 Isolated macular coloboma is rare, usually dominantly inherited, and present at birth without demonstrable progression.13 The term macular coloboma, although in common use, is best avoided as it represents focal dysplasia or atrophy and is unrelated to fetal fissure defects.

Macular degenerative changes in association with high myopia are well described, and can present with chorioretinal atrophy with or without staphyloma, but those changes develop in adults with pathological myopia, and not as a congenital disorder accompanied by nystagmus and reduced vision at a young age.14

This series of four patients further characterises the disorder of myopia with isolated chorioretinal atrophy, demonstrating heterogeneity but a lack of progressive visual loss in childhood. The clinical similarity of the patients in the present series to those previously published, and a presumed recessive inheritance, suggests a distinct diagnostic entity. The disorder can be readily identified and differentiated from other conditions based on presentation and electrophysiology.

References

Iqbal M, Jalili IK . Congenital-onset central chorioretinal dystrophy associated with high myopia. Eye (Lond) 1998; 12 (Pt 2): 260–265.

Bach M, Brigell MG, Hawlina M, Holder GE, Johnson MA, McCulloch DL et al. ISCEV standard for clinical pattern electroretinography (PERG): 2012 update. Doc Ophthalmol 2013; 126 (1): 1–7.

Marmor MF, Fulton AB, Holder GE, Miyake Y, Brigell M, Bach M et al. ISCEV standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2008 update). Doc Ophthalmol 2009; 118 (1): 69–77.

Holder G, Robson A . Paediatric electrophysiology: a practical approach. In: Lorenz B, Moore AT (eds) Pediatric Ophthalmology, Neuro-Ophthalmology, Genetics. Springer: Berlin, 2006 pp 133–152.

Thompson D, Liasis A . Visual electrophysiology: how can it help you and your patient. In: Hoyt C, Taylor D (eds) Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 4th edn Elsevier Limited: London, UK, 2013 pp 55–62.

Michaelides M, Jeffery G, Moore AT . Developmental macular disorders: phenotypes and underlying molecular genetic basis. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96 (7): 917–924.

Sohocki MM, Bowne SJ, Sullivan LS, Blackshaw S, Cepko CL, Payne AM et al. Mutations in a new photoreceptor-pineal gene on 17p cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet 2000; 24 (1): 79–83.

den Hollander AI, Koenekoop RK, Mohamed MD, Arts HH, Boldt K, Towns KV et al. Mutations in LCA5, encoding the ciliary protein lebercilin, cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet 2007; 39 (7): 889–895.

Falk MJ, Zhang Q, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Kannabiran C, Fonseca-Kelly Z, Chakarova C et al. NMNAT1 mutations cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet 2012; 44 (9): 1040–1045.

Boon CJ, Klevering BJ, Cremers FP, Zonneveld-Vrieling MN, Theelen T, Den Hollander AI et al. Central areolar choroidal dystrophy. Ophthalmology 2009; 116 (4): 771–782 782.e771.

Aziz HA, Ruggeri M, Berrocal AM . Intraoperative OCT of bilateral macular coloboma in a child with Down syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 2011; 48 Online: e37–e39.

Gil-Gibernau J, Galan A, Callis L, Rodrigo C . Infantile idiopathic hypercalciuria, high congenital myopia, and atypical macular coloboma: a new oculo-renal syndrome? J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1982; 19 (4): 7–11.

Phillips CI . Hereditary macular coloboma. J Med Genet 1970; 7 (3): 224–226.

Ohno-Matsui K, Akiba M, Moriyama M, Ishibashi T, Hirakata A, Tokoro T . Intrachoroidal cavitation in macular area of eyes with pathologic myopia. Am J Ophthalmol 2012; 154 (2): 382–393.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (UK) and Biomedical Research Centre at Moorfields Eye Hospital and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology, Moorfields Eye Hospital Special Trustees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hull, S., Kalhoro, A., Marr, J. et al. Congenital high myopia and central macular atrophy: a report of 3 families. Eye 29, 936–942 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.53

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2015.53

This article is cited by

-

Subclinical maculopathy and retinopathy in transcobalamin deficiency: a 10-year follow-up

Documenta Ophthalmologica (2022)