Abstract

Objective To investigate geographic inequalities in the provision of NHS orthodontic care in England at the area level.

Methods NHS dental activity data were analysed for the three financial years April 2016 to March 2019. The measures used were units of dental activity (UDA), units of orthodontic activity (UOA) and commencement of orthodontic treatment. Two orthodontic activity indices were created to assess relative volumes of care. Deprivation was measured using the index of multiple deprivations. Slope and relative inequality indices were used to assess inequality.

Results Nearly 12.4 million UOA and 572,987 courses of treatment in England were reported under NHS arrangements in the three years studied. There were significant variations in the rates of UOA (0-716) and UDA (148-918) provided per 100 children (0-17 years) at the local authority level. The variation was not associated with deprivation at the local authority level.

Conclusions There were significant disparities in the provision of NHS orthodontic treatment at the local authority level, but this was not associated with area-level measures of deprivation. Inequality in the uptake of orthodontic care may not be due to area-level disparities in service provision.

Key points

-

Discusses whether commissioning of orthodontic care in England was equal.

-

Area level of orthodontic commissioning inequality was not related to deprivation.

-

Inequality of orthodontic commissioning was not related to the provision of routine dental care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Orthodontic treatment is offered free of charge under NHS arrangements for all children under the age of 18, as well as for some categories of adults.1 Access to orthodontic care is typically via a referral from a general practitioner and good oral health and regular dental attendance are usually prerequisites for any offer of treatment with orthodontic appliances.2 In addition, the NHS imposes eligibility criteria based on the severity of malocclusion as defined by the patient's index of treatment need score.3 Some patients, for example those with complex needs, will receive treatment in secondary care, while some children may also receive care under private arrangements.4 The basic activity indicator for NHS orthodontic care is the unit of orthodontic activity (UOA); the equivalent for routine dental care is the unit of dental activity (UDA). These measures taken together provide a gross indication of volumes of NHS activity.

One of the main NHS principles is the need to attempt to provide equitable access to health services.5,6 Equitable access to oral health outcomes was also mentioned in the 2013 guidance for dental commissioners,7 yet inequality of access to primary and secondary dental services by children is still apparent8,9 and may have worsened as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and continuing problems with access to NHS dental care.10

Since the introduction of local commissioning arrangements for NHS primary dental care in 2006, orthodontic services have been contracted through a mixture of time-limited and in-perpetuity contracts; initially, these reflected historical (provider-led) locations and volumes of provision.11 The 2006 arrangements gave NHS commissioners the power to shape services through new investment or re-commissioning of funds released from the expiry of time-limited contracts; however, the latter process has proved highly contentious.12,13

Malocclusion is one of the few common oral conditions not associated with socioeconomic status,14,15 but, despite this, inequality in uptake of orthodontic care in England is still evident. The 2003 Child dental health survey showed that children aged 15 years old who were eligible for free school meals (an indicator of deprivation) were less likely to wear orthodontic appliances than children from less deprived backgrounds.14 Studies in the North East16 and South East of England17 have all previously found cases of inequality favouring the least deprived in the uptake of NHS orthodontic care at individual level16,17 and such inequality was still apparent in the 2013 Child dental health survey, which identified greater levels of unmet orthodontic need in children from more deprived backgrounds.15 Studies analysing NHS activity data18 and dental survey data19 have found that children from more deprived backgrounds are less likely to obtain orthodontic care. The reasons for this inequality in receiving treatment despite no underlying inequality in need for treatment are unclear but may include relatively lower service provision in deprived localities,20, lack of access to primary care dental services, and underlying inequality in other aspects of oral health, which might render a greater proportion of children from deprived backgrounds ineligible for orthodontic treatment on the basis of risk. This study sought to explore the first of these possibilities in whether NHS orthodontic treatment is systematically less available in more deprived areas.

As access to orthodontic services is inherently dependent upon access to routine dental care, it was necessary to also explore patterns in the latter for comparison.

Objectives

The objectives of this study were to explore, with respect to children in England, whether:

-

The commissioning of NHS orthodontic care was uniform

-

Any observed inequality in the commissioning of such care was related to deprivation

-

Any observed inequality was related to the provision of routine dental care.

Methods

NHS activity data were obtained from the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA)21 for the three financial years from April 2016 to March 2019, inclusive (online Supplementary Information).22 These years were chosen as the most recent years before the disruption to dental services caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, while three years' data were utilised to suppress the effects of any short-term commissioning initiatives or contract terminations which might otherwise have affected figures for some years in certain areas. The allocation of an activity to a particular year was based on the year the activity occurred, rather than the year in which it was claimed, which might be later.22 Withdrawn claims were not included in the data.

'Assess and start appliance' claims were used as an indicator of cases treated.22

NHS activity data were aggregated to lower-tier local authorities based on provider postcode. Data were grouped by the 151 English upper tier local authorities (LAs)23 based on location of provider.

The LAs were ranked based on their 2019 index of multiple deprivations (IMD) average score deprivation levels.24 IMD and population data were obtained from the Office for National Statistics.25

Three indices were developed for each local authority (Box 1). Two inequality indicators were used to assess inequality, as recommended by the World Health Organisation; these were the slope index of inequality (SII) and relative index of inequality (RII).26 The SII and RII are both regression-based analyses that, respectively, summarise the absolute and relative differences between the most affluent and most deprived areas.

The project involved analysis of service data supplied by NHS BSA and no data on individuals were provided, plus the online NHS ethical approval tool indicted no need for ethics committee review; as such, ethical approval was not required.

Results

Summary statistics for the data are shown in Table 1. Over 12 million UOA were provided under NHS arrangements from April 2016 to March 2019, inclusive. A small number of local authorities had no NHS orthodontic provision activity in their area.

The rates of provision are shown in Table 2. These varied considerably between LAs (mean = 247; range = 0-716). Kensington and Chelsea (third quintile) and Southwark (fourth quintile) had no orthodontic provision, while Middlesbrough had the highest rate of orthodontic activity (716 UOA/100 children). The average UDA provision across England for the three financial years examined was 448/100 children. The lowest rate occurred in Coventry (second tier of most deprived LAs) at 148 UDA/100 children, while the highest rate was for Birmingham (among the most deprived LAs; 918 UOA/100 children). Such variations also applied to UDA provision across the whole population (mean = 454; range = 171-2,346), where Richmond upon Thames (least deprived) had the lowest rate of UDA commissioning and Birmingham (most deprived) had the highest.

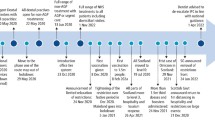

Orthodontic activity indices indicate that NHS orthodontic service provision varied significantly across local authorities (Fig. 1). Figure 1 also shows child population levels and orthodontic activities across local authorities, as reported in detail in Table 2.

Orthodontic activity distribution by LA. Units of orthodontic activity per 100 children by LA. Data from Office for National Statistics and NHS BSA. Shapefile from European Environment Agency. Map created in STATA (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC)

Routine dental activity and orthodontic activities across IMD quintiles are shown in Table 3. The level of routine child dental care (UDAs) tended to be greater in the most deprived areas, with the SII value reaching almost 79. This value indicates that UDAs were provided at a 79% higher rate to the most deprived areas than to the affluent areas. In terms of relative difference (RII), the provided UDA RII values were significantly higher in the most deprived LAs (RII: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.71, 0.98; p = 0.03) than in the affluent LAs. Conversely, the volume of UOAs provided per 100 children was split equally among advantaged (263/100 children) areas and disadvantaged areas (264/100 children). The SII value (SII: 12; 95% CI: -0.65, 0.89) suggests that more UOAs were delivered in the more affluent areas than in the most deprived areas during the period of interest; however, this difference was not significant. The lowest rate of orthodontic activity was seen in the second most deprived LAs quintile (194/100 children).

Discussion

There was a wide variation in levels of commissioned NHS orthodontic care for children at English LA level across the period studied. There was no orthodontic provision in a small number of local authorities, a variation not explained by fewer children in those areas. This also did reflect the provision of routine dental care for children, for example, Southwark, Barking and Dagenham and Swindon have similar numbers of children, while the UOAs provided per 100 children were 0, 147, and 172, respectively. This variation could be due to orthodontic provision being based on historic provider locations established before the introduction of local commissioning in 2006, while another reason might be that, since provision of orthodontic care is focused in fewer locations, this had led to an apparent uneven distribution. However, provision of orthodontic care at fewer locations may lead to longer journey times that can act as a barrier to seeking care, especially for children from more deprived backgrounds.

A key aim of orthodontic commissioning and procurement is to meet the population's needs and to help ensure orthodontic provision equity.19 Previous studies found that normative orthodontic need was nearly similar in the two extreme groups, while the current study shows that orthodontic activity is recorded more commonly in affluent areas than in the most disadvantaged areas. This finding may thus explain observed levels of pro-rich inequality in the experience of orthodontic treatment among children.19

There are several limitations to this study. Importantly, NHS activity data are ecological data that provide area-level information rather than individual data. The postcodes of those patients undergoing orthodontic treatment are thus not known, meaning children's personal deprivation levels could not be accurately assigned. Using this type of data may lead to ecological fallacy, a formal fallacy in data interpretation that occurs when individual data are extrapolated, potentially incorrectly, from that for the group in which the individual belongs. Another limitation of this study is that the IMD, which was used to determine the socioeconomic rankings of the local authorities, does not consider the fact that not everyone who lives in deprived areas is underprivileged, or that not every deprived family live in a deprived area. Finally, the NHS orthodontic activity data utilised included only primary care orthodontic data, excluding hospital orthodontic treatment and private orthodontic treatment. However, this is a more minor limitation, as most of the orthodontic treatment is reported in primary orthodontic care settings rather than within private and hospital orthodontic treatment.2

To further explore the potential contribution of service location with respect to inequalities in the uptake of orthodontic care, it may be useful to look at overarching patterns within local authorities, such as whether orthodontic providers are more likely to locate themselves in the more affluent parts of those authorities. In terms of fully considering volumes of NHS care, it is also important to include NHS care not recorded by UOAs (such as hospital-based care) and private provision to develop a more complete picture. Individual factors may be seen to produce greater barriers than systemic factors in some cases, however, and further research is required to explain apparent inequalities in the receipt of orthodontic care.

Conclusion

There were significant disparities in provision of NHS orthodontic treatment at LA level; however, this was not associated with area-level deprivation. Deprivation-related inequalities in uptake of orthodontic care may not be attributable to area-level disparities in service provision and other factors require exploration.

References

UK Government. The National Health Service (General Dental Services Contracts) Regulations 2005. 2005. Available at https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2005/3361/pdfs/uksi_20053361_en.pdf (accessed March 2023).

NHS England. Guides for commissioning dental specialties - Orthodontics. 2015. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-orthodontics.pdf (accessed November 2022).

NHSBSA. What Is The IOTN? Available at https://faq.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/knowledgebase/article/KA-01983/en-us#:~:text=Index%20of%20Orthodontic%20Treatment%20Needed,The%20Aesthetic%20Component%20(AC) (accessed August 2023).

NHS UK. Overview: Orthodontics. 2020. Available at https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/orthodontics/ (accessed December 2022).

UK Government. Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS white paper. 2010. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/liberating-the-nhs-white-paper (accessed December 2022).

UK Government. Guidance: The NHS Constitution for England. 2023. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-nhs-constitution-for-england/the-nhs-constitution-for-england (accessed August 2023).

NHS England. Securing excellence in commissioning NHS dental services. 2013. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/commissioning-dental.pdf (accessed November 2022).

Nuffield Trust. Root causes: Quality and inequality in dental health. 2017. Available at https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/root-causes-quality-and-inequality-in-dental-health (accessed August 2023).

Ravaghi V, Hargreaves D S, Morris A J. Persistent Socioeconomic Inequality in Child Dental Caries in England despite Equal Attendance. JDR Clin Trans Res 2020; 5: 185-194.

Healthwatch. Our position on NHS dentistry. 2022. Available at https://www.healthwatch.co.uk/news/2022-10-12/our-position-nhs-dentistry (accessed November 2022).

NHS England. Transitional commissioning of primary care orthodontic services. 2013. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/orth-som-nov.pdf (accessed November 2022).

Anonymous. ADG and BDA: pull the plug on ortho tendering. BDJ In Pract 2020; 33: 6.

Anonymous. NHS Commissioning 'very concerning'. BDJ In Pract 2020; 33: 7.

Chestnutt I G, Burden D J, Steele J G, Pitts N B, Nuttall N M, Morris A J. The orthodontic condition of children in the United Kingdom, 2003. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 609-612.

Rolland S, Treasure E, Burden D J, Fuller E, Vernazza C R. The orthodontic condition of children in England, Wales and Northern Ireland 2013. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 415-419.

Morris E, Landes D. The equity of access to orthodontic dental care for children in the North East of England. Public Health 2006; 120: 359-363.

Drugan C S, Hamilton S, Naqvi H, Boyles J R. Inequality in uptake of orthodontic services. Br Dent J 2007; DOI: 10.1038/bdj.2007.127.

Price J C. Socioeconomic position and the National Health Service orthodontic service. Manchester: University of Manchester, 2016. Thesis.

Ravaghi V, Al-Hammadi Z, Landes D, Hill K, Morris A J. Inequalities in orthodontic outcomes in England: treatment utilisation, subjective and normative need. Community Dent Health 2019; 36: 198-202.

Olivia J, Kruger E, Tennant M. Disparities in the geographic distribution of NHS general dental care services in England. Br Dent J 2021; DOI: 10.1038/s41415-021-3005-0.

NHS Business Services Authority. Completion of form guidance - FP170 - England (V2). 2016. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-dental-statistics/2017-18-annual-report (accessed August 2023).

NHS Digital. NHS Dental Statistics for England - 2017-18, Annual Report [PAS]. 2018. Available at https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-dental-statistics/2017-18-annual-report (accessed November 2022).

UK Government. Lower Tier Local Authority to Upper Tier Local Authority (April 2019) Lookup in England and Wales. 2019. Available at https://www.data.gov.uk/dataset/6ee49b1e-0f4d-4079-90f4-b626e36d2035/lower-tier-local-authority-to-upper-tier-local-authority-april-2019-lookup-in-england-and-wales (accessed October 2022).

UK Government. English Indices of Deprivation 2019: Frequently Asked Questions. 2019. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019 (accessed November 2022).

Office for National Statistics. Population estimates - small area based by single year of age - England and Wales. 2019. Available at https://www.nomisweb.co.uk/query/construct/summary.asp?mode=construct&dataset=2010&version=0 (accessed November 2022).

World Health Organisation. Handbook on Health Inequality Monitoring: with a special focus on low- and middle-income countries. 2013. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85345 (accessed August 2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the NHSBSA for providing the orthodontic activity data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors conceived the study. Zinab Al-Hammadi designed the study, analysed the data and did the write-up. Alexander J. Morris was involved in the design of the study, analysis of data and write-up. Vahid Ravaghi was involved in the analysis and write-up. Kirsty Hill was involved in the write-up. Zinab Al-Hammadi is the guarantor of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

This project involved analysis of service data supplied by NHS BSA and no data on individuals were provided. We have used the online NHS ethical approval tool for this study and the result indicted no need for NHS REC review. As such, ethical approval was not required.

Dental data were supplied by NHSBSA and the IMD data from the publicly available source at (https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2019) and can be made available upon request.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.© The Author(s) 2023

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Hammadi, Z., Ravaghi, V., Hill, K. et al. Area-level inequalities in the provision of NHS orthodontic care in England from 2016 to 2019. Br Dent J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6273-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6273-z