Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of vitrectomy with inverted internal limiting membrane (ILM) flap for the treatment of macular hole retinal detachment (MHRD) in high myopia compared with that of ILM peeling.

Methods

PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, MEDLINE, Ovid, Wan Fang and CNKI were systematically reviewed. The primary outcome parameters were the MH closure rate, retinal reattachment rate and postoperative BCVA. Secondary outcome parameters, included intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Results

Seven retrospective comparative studies including 228 eyes were selected. No significant difference was detected in either postoperative BCVA (MD −0.07; 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.03; p = 0.16) or the improvement in postoperative BCVA (MD −0.17; 95% CI: −0.50 to 0.16; p = 0.32) between the ILM flap group and ILM peeling group. The retinal reattachment rate using inverted ILM flap was not significantly different from that using ILM peeling (odds ratio (OR) 2.24; 95% CI: 0.75–6.73; p = 0.15). The MH closure rate was higher with inverted ILM flap than with ILM peeling (OR 11.86; 95% CI: 5.65 to 24.92; p < 0.00001). There was no significant difference in intraoperative or postoperative complications, including concomitant cataract rate (OR 1.22; 95% CI: 0.42–3.58; p = 0.71).

Conclusion

The inverted ILM flap technique could contribute to a higher MH closure rate than ILM peeling, but visual improvement was similar. Both surgical methods could obtain a high-retinal reattachment rate with fewer intraoperative and postoperative complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Macular hole retinal detachment (MHRD) in patients with high myopia is an intractable problem for ophthalmologists. In patients with MH myopia, the incidence of RD increased as myopia worsened (97.6% RD in myopia over −8.25 D, 67.7% RD in myopia between −8.0 and −3.25 D and 1.1% RD in myopia under −3.0 D) [1, 2]. High myopia is often associated with posterior staphyloma and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy, increasing the tangential macular traction of the vitreoretinal interface, likely causing RD and MH. Various surgical methods have been compared in MHRD, including pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with or without ILM removal, episcleral macular buckling, scleral imbrication and the posterior episcleral buckle procedure [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In some studies, vitrectomy with ILM peeling contributed to successful retinal reattachment and MH closure, representing an effective treatment for MHRD in high myopia [10,11,12,13]. Others have indicated that MH closure is difficult to attain, although ILM removal eases tangential macular traction. In addition, the final visual acuity seldom increased, especially in patients with high myopias [14, 15]. Recently, Michalewska proposed using an inverted ILM flap technique for the treatment of MH with diameters greater than 400 μm [16]. Next, this technique was applied to myopic MHRD [17, 18]. Therefore, this meta-analysis was used to determine whether the inverted ILM flap technique improved the anatomic and functional outcomes of MHRD in high myopia compared with the ILM peeling technique.

Methods

Search strategy

PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, MEDLINE, Ovid, Wan Fang and CNKI were searched. All related articles were published before 14 February 2018 in Chinese or English.

The following search terms were used: (‘macular hole’ OR MH) AND (‘retinal detachment’ OR RD) AND (‘myopic’ OR ‘myopia’) AND (‘vitrectomy’) AND (‘internal limiting membrane peeling’ OR ‘inverted internal limiting membrane flap’ OR ‘inverted internal limiting membrane insertion’ OR ‘internal limiting membrane repositioning’ OR ‘ILM peeling’ OR ‘ILM flap’).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All studies included in this meta-analysis followed the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria includes the following: (1) patients with high myopia and MHRD; (2) a comparison of the ILM flap technique and ILM peeling technique; (3) records of reattachment rate, MH closure rate and BCVA and (4) a follow-up time of no less than 6 months.

Exclusion criteria includes the following: (1) previous history of PPV; (2) presence of peripheral retinal break or proliferative vitreoretinopathy or trauma before the primary surgery and (3) use of scleral buckling, including macular buckling in the primary study.

Data collection and risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted the data and evaluated the quality. If the two reviewers disagreed, a third reviewer analysed the data and quality.

The following variables were extracted from each study: first author, publication year, design, postoperative follow-up time, sample size, ILM staining, tamponade and measured outcomes. The main measured outcomes were BCVA (converted to logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) for clarity and statistical comparison purposes), MH closure rate and retinal reattachment rate. The secondary measured outcomes included intraoperative or postoperative complications.

All included studies were assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which provided a score from a possible total of nine stars [19, 20].

Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot of the data and Egger’s test.

Data synthesis and analysis

We used the Q-statistic test and I2 statistic test to assess the heterogeneity between studies. A p value < 0.1 was considered statistically significant for the Q-statistic test.

I2 ranges from 0 to 100% (a value of 0% represents no heterogeneity, 0% < I2 < 25% represents mild, 25% ≤ I2 < 50% represents moderate, 75% ≤ I2 represents great heterogeneity) [21, 22]. If there was significant heterogeneity between studies, a random-effect model was employed. Otherwise, a fixed-effect model was used.

The results of individual studies were pooled using Review Manager software (V.5.3, the Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England). In addition, subgroup analyses with dyes and tamponades were used for the study of heterogeneity. A p value < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference between studies. The sensitivity analysis was performed using Stata software (V.12.0; Stata, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Search results

A total of 438 relevant studies were identified through our initial search, and 316 studies remained after removing duplicates. By screening titles and abstracts, 241 studies were excluded. After assessing the full-text articles, 7 of these studies [23,24,25,26,27,28,29] were eligible for inclusion (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies

The summary characteristics and quality assessment of 7 studies are explained in Table 1. A total of 228 eyes underwent PPV with the inverted ILM flap technique (110 eyes) or ILM peeling technique (118 eyes) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Four studies [23,24,25, 29] stained the ILM with BBG and other three studies [26,27,28] stained it with ICG. For the tamponades, gas was used in four studies [23,24,25,26] and silicone oil was used in one study [28]. The other two studies [27, 29] used gas or silicone oil. All studies were considered retrospective comparative studies. The follow-up time was at least 6 months (6–36 months). The Newcastle-Ottawa scale was used to present the risk of bias for the included studies (Supplementary Table 1). The scores ranged from 6 to 9. The quality of the studies was medium to good. There was no significant difference in preoperative BCVA between the ILM flap group and the ILM peeling group (MD −0.03; 95% CI: −0.16 to 0.09; p = 0.60; Fig. 2a).

Forest plot. a Forest plot comparing the preoperative BCVA (logMAR) between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD. BBG group represented BBG was used to stain ILM; ICG group represented ICG was used to stain ILM. b Forest plot comparing the postoperative BCVA (logMAR) between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD. BBG group represented BBG was used to stain ILM; ICG group represented ICG was used to stain ILM. c Forest plot comparing the improvement in postoperative BCVA (logMAR) between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD. d Forest plot comparing the retinal reattachment rate between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD. BBG group represented BBG was used to stain ILM; ICG group represented ICG was used to stain ILM. e Forest plot comparing the MH closure rate between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD.BBG group represented BBG was used to stain ILM; ICG group represented ICG was used to stain ILM. f Forest plot comparing the concomitant cataract rate between the inverted ILM flap group and ILM peeling group in high myopia with MHRD

Outcomes

Main outcomes

No significant difference was detected in either postoperative BCVA (MD −0.07; 95% CI: −0.17 to 0.03; p = 0.16; Fig. 2b) or the improvement in postoperative BCVA (MD −0.17; 95% CI: −0.50 to 0.16; p = 0.32; Fig. 2c) between the ILM flap group and ILM peeling group. The retinal reattachment rate using inverted ILM flap was not significantly different from that using ILM peeling (odds ratio (OR) 2.24; 95% CI: 0.75–6.73; p = 0.15; Fig. 2d). The MH closure rate was higher with inverted ILM flap than with ILM peeling (OR 11.86; 95% CI: 5.65–24.92; p < 0.00001; Fig. 2e).

In the subgroup analysis, whether using BBG or ICG staining ILM, there was no statistical difference in either postoperative BCVA (p = 0.07; p = 0.56; Fig. 2b) or the retinal reattachment rate (p = 0.50; p = 0.16; Fig. 2d) between the ILM flap group and ILM peeling group. And the MH closure rate was still significantly higher in the ILM flap group (p < 0.0001; p < 0.00001; Fig. 2e). The subgroup analysis of the tamponades revealed that whether it was filled with gas or filled with silicone oil, no significant difference was detected in either postoperative BCVA (p = 0.62; p = 0.48; Supplementary Fig. 3b) or the retinal reattachment rate (p = 0.11; p = 0.38; Supplementary Fig. 3c) between the two surgery groups and the MH closure rate was also significantly higher in the inverted ILM flap group (p < 0.00001; p = 0.005; Supplementary Fig. 3d).

Secondary outcomes

There was no significant difference in intraoperative or postoperative complications, including concomitant cataract rate (OR 1.22; 95% CI: 0.42–3.58; p = 0.71; Fig. 2f).

No MH reopening was reported in three studies [25, 26, 29]. Four included studies [25,26,27,28] reported recurrence rates of RD, and only two cases occurred in the ILM peeling group in a study by Shen et al. [27]. Regarding the chorioretinal atrophy rate, two cases occurred in the ILM flap group and one in the ILM peeling group in a study by Takahashi et al. [29], while none were reported in a study by Xu et al. [25].

Publication bias

Publication bias of the main outcomes was assessed by using a funnel plot of the data or Egger’s test. No significant publication bias was observed (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Sensitivity analysis

Stata software was used to conduct sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Studies on the MH closure rate and postoperative BCVA had good stability. However, the sensitivity analysis of the retinal reattachment rate indicated that the result depended on the inclusion of one study [29]. When this study [29] was excluded from the meta-analysis, the retinal reattachment rate of the ILM flap technique was higher than that of the ILM peeling technique, and the difference was statistically significant.

After the inclusion of the study [29], the difference was not statistically significant.

In addition, the improvement in postoperative BCVA showed that when this study [26] was excluded, a significant difference between the two groups appeared.

Discussion

Outcomes analysis

To the best of our knowledge, this meta-analysis is the first to assess the efficacy and safety of inverted ILM flap versus ILM peeling for patients with high myopia MHRD. We reviewed seven comparative studies involving a total of 228 eyes that underwent PPV with inverted ILM flap or ILM peeling. The pooled outcomes from this meta-analysis indicated that the ILM flap group achieved a higher MH closure rate. However, no significant difference was detected between the two groups in the improvement in postoperative BCVA and retinal reattachment rate after initial surgery. In addition, intraoperative and postoperative complications showed no significant differences.

Retinal reattachment

All the included studies reported the success rate of primary retinal reattachment. In this meta-analysis, both the inverted ILM flap and ILM peeling groups had high-reattachment rates (97.3% and 91.5%, respectively), with no significant difference identified [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. Also, in the subgroup analyses of dyes and tamponades, there was no statistical difference in retinal reattachment rate between the ILM flap group and ILM peeling group. However, sensitivity analysis suggested that the results were affected a lot by the study [29], and the studies on retinal reattachment rate were unstable. This might be because the postoperative retinal reattachment rate of ILM flap technique was lower than that of ILM peeling technique in the study of Takahashi et al. [29], whereas in the other six studies included, the retinal reattachment rates of ILM flap technique were not lower than those of ILM peeling technique. The opposite study [29] accounted for a certain weight in the meta-analysis, leading to different statistical results. In the study of Takahashi et al. [29], three intravitreal tamponades were used, including C3F8, SF6 and SO (silicone oil). In the other included six studies, four studies [23,24,25,26] used non-expansive gases (C3F8 or SF6), one study [28] used SO and the other [27] used gas/SO. One study [26] showed prolonging the filling time of SO might help overcome the weakening of the chorioretinal adhesion and result in a high anatomical success rate. However, our subgroup analysis of tamponades revealed whether it was filled with gas or filled with silicone oil, no significant difference was detected in retinal reattachment rate between the ILM flap group and ILM peeling group.

Considering the number of cases in each subgroup was small, especially in the silicone oil group, the influence of different tamponades on the rate of retinal reattachment was controversial.

Macular hole closure

The studies included in our meta-analysis showed that the MH closure rate in the inverted ILM flap group ranged from 75 to 100%, while it ranged from 25 to 88.9% in the ILM peeling group. In addition, the inverted ILM flap group had a significantly higher MH closure rate than did the ILM peeling group [23,24,25,26,27,28,29], although the dyes and intravitreal tamponades used in the included studies were different.

Michalewska proposed that inverted ILM flap provided scaffolding for the proliferation of glial cells. Moreover, this flap was beneficial to the repair of MH [16, 18].

According to Kuriyama et al. [30], a high-MH closure rate and successful anatomic reduction were attained in MHRD myopic eyes by PPV with the inverted ILM flap technique. This report and our meta-analysis confirmed that compared with the ILM peeling technique, the inverted ILM flap technique significantly improved the MH closure rate for MHRD high-myopia eyes.

Postoperative BCVA

Both groups showed improvement in postoperative visual acuity to a certain extent.

This improvement was related to the success of MH closure and macular anatomy recovery. In contrast to expectations, there was no statistical difference in visual acuity improvement, even though the inverted ILM flap group had a higher MH closure rate than did the ILM peeling group [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. And the subgroup analyses of meta-analysis showed the result of postoperative BCVA was not affected by the differences of dyes or intravitreal tamponades. Whether using BBG or ICG to stain ILM, no statistical difference was detected between the two surgery groups. However,the subtotal mean difference (MD) of postoperative BCVA (logMAR unit, mean ± SD) using BBG (MD = −0.19) was much smaller than that using ICG (MD = −0.03). It seemed that the dyes might have effects on the recovery of postoperative BCVA and BBG was probably superior to ICG. In the subgroup analysis of tamponades, whether it was filled with gas or filled with silicone oil, the ILM flap technique showed no statistically significant difference in postoperative BCVA with ILM peeling technique.

The subtotal MD in SO group(MD = −0.09)was slightly less than that in gas group (MD = −0.06). Whether SO was more beneficial to vision recovery than gas required more clinical studies to confirm.

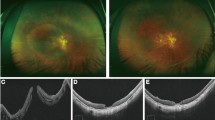

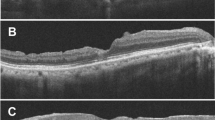

The lack of a difference in postoperative BCVA may be related to the following reasons. High myopia is often associated with chorioretinal atrophy, and the foveal photoreceptor layer may have been destroyed before surgery. Thus, the foveal structure of the outer retinal layer may be unrecoverable after surgery [31]. In addition, an inverted ILM flap could lead to excessive activation of glial cells in the foveal centre, which is not beneficial to the recovery of visual function [32, 33]. We cited some OCT images (Supplementary Figure 4) [24, 29]. MH and RD could be seen from preoperative OCT. After the inverted ILM flap surgery, postoperative OCT showed the retina was reattached and the MH closed. Postoperative BCVA improved to different degrees (Supplementary Fig. 4a and b) [24, 29]. Postoperative OCT demonstrated structures that could be observed during the closure of MH, including external limiting membrane, ellipsoid zone, the outer nuclear layer (ONL) and hyperreflective bridging tissue with or without retinal layers (Supplementary Fig. 4c–f) [24, 29]. In a study by Takahashi et al., the spectral domain-OCT and swept source-OCT images of eyes treated with the inverted ILM flap technique suggested that the closed MH comprised tissues that had migrated into the MH. In the inverted group, the ONL was detected in 50% of the closed MH. This finding could indicate that ILM tissue may help photoreceptor cells translocate to the closed MH, leading to visual improvement. In 17% of the closed MH, hyperreflective bridging tissue was found. This finding could indicate that the MH was closed with scarred tissue or migrated glial tissue, including collagen components derived from the inverted ILM or Müller cells. This tissue blocked the recovery of the foveal structure and may cause central visual disturbances, scotomas, or distorted vision [29, 34]. It suggested that the improvement of postoperative visual acuity might be related to the recovery of the structural level of the macular area. Moreover, the presence of ILM in the hole inevitably increased dye retention. Dye, especially ICG, could have toxic effects on retinal tissue, such as RPE atrophy [35, 36]. Additionally, a short follow-up time may result in incomplete repair of the macular structure, and the recovery of visual function was insufficient. Moreover, the duration of the RD or MH was an important prognostic factor in the treatment of patients with MHRD high myopia [14, 37].

Intraoperative and postoperative complications

No serious complications, such as endophthalmitis and intraocular haemorrhage, were reported in the included studies. Other intraoperative and postoperative complications, such as recurrence of RD, reopening of MH, concomitant cataract and chorioretinal atrophy, showed no significant differences between the two groups at the final follow-up.

Limitations

A total of 7 retrospective studies involving 228 eyes were eligible under our strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. No significant publication bias was observed. We carefully compared the selection bias and the influence of confounders among the included studies. No significant difference was detected in the preoperative BCVA.

Considering the possible effects of different dyes and tamponades on our results, the subgroup analyses were performed. However, the articles included in the meta-analysis lacked specific data of OCT and the correlation analysis between OCT and visual acuity. Further clinical studies were needed to provide more OCT related data for statistical analysis to confirm the relationship between OCT performance and vision recovery. The follow-up time in each study was also different and not long enough, which could lead to differences and corresponding deviations. In addition, data on the improvement in postoperative BCVA were obtained from only three studies, and significant heterogeneity was detected. This issue might limit the reliability of this finding and affect the interpretation of the results. In addition, the sensitivity analysis of the retinal reattachment rate indicated that the result depended on the inclusion of one study [29]. When this study [29] was excluded from the meta-analysis, a significant difference between the ILM flap and ILM peeling groups appeared.

Moreover, this study was limited to published articles, and other studies may be ongoing or unpublished at the peer review stage.

Prospects for the future and improvement

More standard-designed studies with prospective randomised control that incorporate larger sample sizes and longer follow-up times are needed to provide more reliable evidence in evaluating the effect of the ILM flap on macular function. The residual ICG in the inverted ILM flap may be potentially toxic to the retina; thus, using a safer dye (such as BBG) is necessary. To prevent the displacement of the ILM flap, Lai et al suggested using autologous blood clots [38]. These authors reported that the MH closure rate was 96% and only required patients to remain in a facedown position for a short time. However, the introduction of foreign blood may increase the possibility of infection. Additionally, perfluorocarbon liquid was used before fluid–air exchange in a study by Shi et al to ensure that the inverted ILM flap completely covered the MH [33].

High myopia is usually accompanied by a long axial length and posterior staphyloma, leading to retinal thinning and increased fragility. The process of peeling the ILM and reversing the flap or stuffing the MH was technically difficult. Therefore, future studies are needed to provide improved surgical methods for better safety and efficacy for MHRD in high myopia.

Conclusions

The inverted ILM flap technique could contribute to a higher MH closure rate than ILM peeling, whereas visual improvement was similar between these techniques.

Both surgical methods could obtain a high-retinal reattachment rate with fewer intraoperative and postoperative complications. The inverted ILM flap technique may become the standard treatment for patients with MHRD high myopia in the future with improvements in surgical methods.

Summary

What was known before

The treatment for MHRD in patients with high myopia is not obvious.

Both the inverted ILM flap and ILM peeling techniques can be used for MHRD in high myopia, whereas the comparison between the two treatments is unknown.

What this study adds

The inverted ILM flap technique contributed to a higher MH closure rate than did ILM peeling, whereas visual improvement was similar for MHRD high myopia.

Both surgical methods could obtain a high retinal reattachment rate with less intraoperative and postoperative complications for MHRD high myopia.

The inverted ILM flap technique is a useful treatment for MHRD high myopia.

References

Morita H, Ideta H, Ito K, Yonemoto J, Sasaki K, Tanaka S. Causative factors of retinal detachment in macular holes. Retina. 1991;11:281–4.

Ishida S, Yamazaki K, Shinoda K, Kawashima S, Oguchi Y. Macular hole retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes: ultrastructure of surgically removed epiretinal membrane and clinicopathologic correlation. Retina. 2000;20:176–83.

Li X, Wang W, Tang S, Zhao J. Gas injection versus vitrectomy with gas for treating retinal detachment owing to macular hole in high myopes. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1182–7.

Chen YP, Chen TL, Yang KR, Lee WH, Kuo YH, Chao AN, et al. Treatment of retinal detachment resulting from posterior staphyloma-associated macular hole in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2006;26:25–31.

Ripandelli G, Coppe AM, Fedeli R, Parisi V, D’Amico DJ, Stirpe M. Evaluation of primary surgical procedures for retinal detachment with macular hole in highly myopic eyes: a comparison [corrected] of vitrectomy versus posterior episcleral buckling surgery. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:2258–64.

Fujikawa M, Kawamura H, Kakinoki M, Sawada O, Sawada T, Saishin Y, et al. Scleral imbrication combined with vitrectomy and gas tamponade for refractory macular hole retinal detachment associated with high myopia. Retina. 2014;34:2451–7.

Lim LS, Tsai A, Wong D, Wong E, Yeo I, Loh BK, et al. Prognostic factor analysis of vitrectomy for retinal detachment associated with myopic macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:305–10.

Seike C, Kusaka S, Sakagami K, Ohashi Y. Reopening of macular holes in highly myopic eyes with retinal detachments. Retina. 1997;17:2–6.

Ando F, Ohba N, Touura K, Hirose H. Anatomical and visual outcomes after episcleral macular buckling compared with those after pars plana vitrectomy for retinal detachment caused by macular hole in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2007;27:37–44.

Uemoto R, Yamamoto S, Tsukahara I, Takeuchi S. Efficacy of internal limiting membrane removal for retinal detachments resulting from a myopic macular hole. Retina. 2004;24:560–6.

Oie Y, Emi K, Takaoka G, Ikeda T. Effect of indocyanine green staining in peeling of internal limiting membrane for retinal detachment resulting from macular hole in myopic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:303–6.

Kuhn F. Internal limiting membrane removal for macular detachment in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135:547–9.

Sayanagi K, Ikuno Y, Tano Y. Tractional internal limiting membrane detachment in highly myopic eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:850–2.

Ichibe M, Yoshizawa T, Murakami K, Ohta M, Oya Y, Yamamoto S, et al. Surgical management of retinal detachment associated with myopic macular hole: anatomic and functional status of the macula. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:277–84.

Nadal J, Verdaguer P, I. M. CanutTreatment of retinal detachment secondary to macular hole in high myopia:vitrectomy with dissection of the inner limiting membrane to the edge of the staphyloma and long-term tamponade. Retina. 2012;32:1525–30.

Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Adelman RA, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:2018–25.

Kinoshita T, Onoda Y, Maeno T. Long-term surgical outcomes of the inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique in highly myopic macular hole retinal detachment. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;255:1101–6.

Michalewska Z, Michalewski J, Dulczewska-Cichecka K, Nawrocki J. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for surgical repair of myopic macular holes. Retina. 2014;34:664–9.

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa, Ontario: Ottawa Health Research Institute, University of Ottawa; 2015. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm. Accesed 30 Oct 2015.

Herzog R, Álvarez-Pasquin MJ, Díaz C, Del Barrio JL, Estrada JM, Gil Á. Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:154.

Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Heterogeneity in meta-analyses of genome-wide association investigations. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e841.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. Br Med J. 2003;327:557–60.

Baba R, Wakabayashi Y, Umazume K, Ishikawa T, Yagi H, Muramatsu D, et al. Efficacy of the inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique with vitrectomy for retinal detachment associated with myopic macular holes. Retina. 2017;37:466–71.

Sasaki H, Shiono A, Kogo J, Yomoda R, Munemasa Y, Syoda M, et al. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique as a useful procedure for macular hole-associated retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. Eye. 2017;31:545–50.

Xu C, Wu J, He J, Feng C. Observation of single-layered inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for macular hole with retinal detachment in high myopia. Chin J Ophthalmol. 2017;53:338–40.

Chen SN, Yang CM. Inverted internal limiting membrane insertion for macular hole-associated retinal detachment in high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2016;162:99–106.

Shen Y, Yao J, Jiang Q. Vitrectomy combined with internal limiting membrane insertion for the treatment of high myopia with macular hole retina detachment. Acta Univ Med Nanjing (Nat Sci). 2017;37:378–81.

Sun G, Xu X, Shen Y, Yao J. The clinic outcomes of inverted internal limiting membrane flap for macular hole retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. J Clin Ophthalmol. 2017;25:231.

Hiroyuki T, Makoto I. Inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for treatment of macular hole retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. Retina. 2017;1–10.

Kuriyama S, Hayashi H, Jingami Y, Kuramoto N, Akita J, Matsumoto M, et al. Efficacy of inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for the treatment of macular hole in high myopia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156:125–31.

Hayashi H, Kuriyama S. Foveal microstructure in macular holes surgically closed by inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique. Retina. 2014;34:2444–50.

Song Z, Li M, Liu J, Hu X, Hu Z, Chen D. Viscoat assisted inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for large macular holes associated with high myopia. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:8283062.

Shin MK, Park KH, Park SW, Byon IS, Lee JE. Perfluoro-n-octane-assisted single-layered inverted internal limiting membrane flap technique for macular hole surgery. Retina. 2014;34:1905–10.

Arias L, Caminal JM, Rubio MJ, Cobos E, Garcia-Bru P, Filloy A, et al. Autofluorescence and axial length as prognostic factors for outcomes of macular hole retinal detachment surgery in high myopia. Retina. 2015;35:423–8.

Imai H, Azumi A. The expansion of RPE atrophy after the inverted IML flap technique for a chronic large macular hole. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2014;5:83–86.

Nakanishi H, Kuriyama S, Saito I, Okada M, Kita M, Kurimoto Y, et al. Prognostic factor analysis in pars plana vitrectomy for retinal detachment attributable to macular hole in high myopia: a multicenter study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:198–204.

Lam RF, Lai WW, Cheung BT, Yuen CY, Wong TH, Shanmugam MP, et al. Pars plana vitrectomy and perfluoropropane (C3F8) tamponade for retinal detachment due to myopic macular hole: a prognostic factor analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:938–44.

Lai CC, Chen YP, Wang NK, Chuang LH, Liu L, Chen KJ, et al. Vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane repositioning and autologous blood for macular hole retinal detachment in highly myopic eyes. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:1889–98.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, Q., Luan, J. Vitrectomy with inverted internal limiting membrane flap versus internal limiting membrane peeling for macular hole retinal detachment in high myopia: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Eye 33, 1626–1634 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0458-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0458-3