Abstract

The human right to health is universal and non-exclusionary, supporting health in full, and for all. Despite advances in health systems globally, 3.6 billion people lack access to essential health services. Women and girls are disadvantaged when it comes to benefiting from quality health services, owing to social norms, unequal power in relationships, lack of consideration beyond their reproductive roles and poverty. Self-care interventions, including medicines and diagnostics, which offer an additional option to facility-based care, can improve the autonomy and agency of women in managing their own health. However, tackling challenges such as stigma is essential to avoid scenarios in which self-care interventions provide more choice for those who already benefit from access to quality healthcare, and leave behind those with the greatest need. This Perspective explores the opportunities that self-care interventions offer to advance the health and well-being of women with an approach grounded in human rights, gender equality and equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The human right to health is universal and non-exclusionary. It is not a right to some health for some—but to health in full, and for all. Yet the global footprint of health access today falls far below that standard, with half of the world’s population lacking access to essential health services1. This is especially true for women living outside the reach of government-administered health systems or pushed into extreme poverty because of healthcare that is overpriced, under-resourced and ill-equipped to meet their needs, priorities and rights. Against global and regional contexts, in which Member States’ promises to human rights in and through health are widespread but unevenly fulfilled, innovations in healthcare are urgently needed. The term ‘women’ covers an inclusive approach to all women, girls and gender-diverse individuals across their life course and a diversity of lived experiences, including but not limited to individuals with disabilities, those experiencing homelessness, those undergoing incarceration and/or institutionalization, those undergoing displacement due to wars and conflicts, those living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Indigenous individuals and those belonging to minority, racial or ethnic groups.

Self-care interventions are among the most promising strategies to improve health coverage for women worldwide. During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the prioritization of access to self-care interventions—such as over-the-counter multi-month contraception through pharmacies, or telehealth counseling during pregnancy—across countries spanning the income spectrum—clearly demonstrated the ability of women who did not have formal health training to take measures to manage their health and protect themselves2. However, access to quality self-care interventions needs to move beyond being a response that is considered only during times of crisis and global emergencies, to one that becomes an integral part of routine healthcare. Calls for greater emphasis on self-care interventions as additional options to health facility-based care led to the development of a global normative guideline by the World Health Organization (WHO), with evidence-based recommendations relevant for every economic setting3.

In this Perspective, we explore the scope of self-care interventions with the potential to improve the health and well-being of women in the context of a safe, supportive and enabling environment. We explore the barriers that currently limit this potential and outline strategies to sustainably integrate self-care interventions into health systems, building upon examples of WHO evidence-based recommendations.

Scope of self-care interventions

Self-care existed well before the establishment of modern health systems4. Across the world, people engage in self-care to promote and maintain their health, to prevent disease and to cope with illness and disability, sometimes with and sometimes without a health or care worker5. Which practices people can and do choose to engage in, for themselves or for those in their care, is heavily context dependent. Factors such as health literacy, access to information, the social environment and individual or family agency all play a role. For instance, improving health literacy in populations provides the foundation for citizens to play an active role in improving their own health, to engage successfully with community action for health and mobilize governments to meet their responsibilities for health and health equity. Fundamentally, improving health literacy enables people to better interpret, understand and act on health information for better self-care.

Self-care interventions are the first point of entry for the following: (i) engaging people and communities to take an active role in their health and their health services; (ii) supporting integrated health services that meet the needs of individuals and communities across their life course; and (iii) people-centered multisectoral policy and action, to address broader determinants of health—three aspects that are the foundation of primary healthcare and the cornerstone of resilient health systems6,7,8,9. Self-care interventions are also relevant across the life course of women to improve their overall health trajectory (Table 1) and cover a range of health topics, including sexual and reproductive health (Box 1).

The WHO definition of self-care and self-care interventions is supported by a conceptual framework10 (Fig. 1) that places people at the center, both in their role of caring for themselves and in their role as caregivers. The framework aims to ensure that all individuals, including those who may fall through the cracks of existing health systems, are considered by policymakers and implementers planning the promotion, introduction and scale-up of quality self-care interventions to improve coverage and equity.

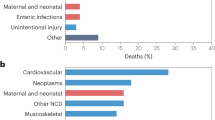

Although women have been self-managing their own health for millennia, the development of products such as modern contraceptives and digital health interventions have transformed the landscape of women’s health and rights and their ability to make informed decisions11,12,13,14. The past two decades have seen the accumulation of strong evidence on the potential of self-care options for a wide range of health conditions, including sexual and reproductive health15, chronic diseases16, mental health17 and, more recently, COVID-19 (ref. 18). Strong evidence exists regarding the effectiveness of self-care strategies such as diet and exercise, in supporting various individual, family-based and community-based approaches in, for instance, cardiovascular treatment plans19. Sexual and reproductive health is another area where self-care interventions have enormous potential. Although not exhaustive, the following sections provide an overview of the scope of self-care interventions in these key areas of women’s health.

Healthy behaviors and lifestyle

Health practices, behaviors, capacities and decisions are framed by the context of the lives of women20. Women with hypertension or preeclampsia during pregnancy have more than double the risk for a future diagnosis of, or death from, cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease than women who do not have these conditions during pregnancy21,22. Maternal obesity increases the risk of children developing cardiovascular risk factors and disease at a younger age23. Consequently, self-care actions such as not smoking, avoiding obesity, being physically active and eating a heart-healthy and low-sodium diet, can help women to reduce or avoid noncommunicable diseases across the life course24. However, not all women have access to such interventions, nor the resources to commit and adhere to the recommended self-care practices. For instance, increasing intake of nutrients, such as those found in fruits, vegetables or fiber, may be too expensive or unavailable for low-income mothers25,26. Further, women have varying perceptions of health risks that shape their values and preferences toward, and ability to engage in, self-care. For instance, older women can be at risk of multimorbidity with a range of co-occurring, interacting conditions such as arthritis, hypertension and diabetes, each of which require different self-care actions27,28. Living with more than one chronic illness can also reduce the ability to monitor and differentiate the cause of a particular symptom29. Approaches to prevention, treatment and healing are also socially and culturally different among diverse societies and populations30.

Contraception

In Uganda (Box 2) and several other countries in Africa, there is evidence of benefits for women and adolescent girls regarding self-administration of injectable subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA-SC, a contraceptive)31,32,33,34. Research using different study designs (including a randomized control trial) consistently finds that women who are trained to self-administer DMPA-SC and provided with units for home use have improved adherence and reduced expenses because of fewer resupply trips to health facilities—making self-injection a cost-effective intervention35,36. Cost and convenience are of particular benefit to women living in remote, rural areas, for whom travel costs are high and visiting a health facility may require a full day37,38.

Self-injectable DMPA-SC also offers the potential for enhanced privacy by reducing visits to public facilities where discreet users risk discovery. Whether self-injection is privacy enhancing for a woman or adolescent depends on her degree of agency and privacy in her home. Considering the benefits of offering women this choice, nearly 30 countries, including Uganda, are currently introducing or scaling up provision of self-administered DMPA-SC, according to WHO recommendations39.

Nevertheless, while self-injection may advance women’s self-efficacy and autonomy, women who already possess agency may be better able to take advantage of self-care services, raising the question of how to improve access, particularly for those with limited agency and autonomy40. Also to note, self-injection of DMPA-SC often requires an upfront investment of additional health-care provider time to train clients and/or funds for client training materials. Health system cost savings are not always immediate, but savings could potentially accrue over time if the client continues to practice self-care with limited provider support36.

STIs, including HIV prevention and treatment

Young women in sub-Saharan Africa bear a disproportionate brunt of the global burden of HIV infection41. Their risk of infection arises primarily from age-disparate sexual relationships with men who are, on average, 7–11 years older than them being the primary source of infection42. Notwithstanding gendered power disparities that influence these sexual relationships, the available HIV prevention technologies favor men.

The development of women-initiated discreet prevention technologies was a long and slow road marked with many failures43,44. However, the rapid expansion of simple, near-patient care and self-testing has created an opportunity to enhance access to quality prevention and treatment services. This is particularly salient in resource-limited settings where there are numerous barriers to laboratory-based testing and limited access to health services, which notably impact women more than men. Use of point-of-care (POC) sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing has led to prompt management and clearance of STIs45,46, and increased task sharing to women and community support workers and away from more formal health centers and clinicians. HIV self-testing has contributed to countries’ efforts to support women, including female sex workers and women living in humanitarian settings, to learn their HIV status and access treatment if needed47,48.

Currently, daily oral tablets of tenofovir in combination with emtricitabine pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are widely available to the public in most primary health-care clinics in sub-Saharan Africa. Yet uptake is modest, and persistent use over 12 months is limited49,50. Community empowerment programs are central to supporting key populations at high risk of HIV to achieve prevention and treatment objectives, and there is some evidence of increasing uptake in young women when PrEP is offered through mobile health services and peer outreach51,52. Evidence-based strategies to increase uptake and adherence among populations at risk of HIV are urgently needed if we are to realize the full potential of these new technologies, and meet the United Nations 2030 goals to end AIDS as a public health threat. Policy, access and affordability are still barriers to the expansion of PrEP options, including the monthly dapivirine ring and cabetogravir injections. Urgent attention is needed to shorten the time from evidence to action for HIV prevention technologies.

Self-testing for HIV and POC STI testing provide important entry points to reach underserved communities, including young women53. For women living with HIV on antiretroviral treatment, POC viral load monitoring and multi-month treatment dispensation has enhanced rates of therapeutic success54,55. The use of novel POC drug level testing is also being utilized for enhancing adherence through targeted adherence support56. However, there remains limited evidence on self-administration of these monitoring tests and self-care for these conditions in resource-limited settings, particularly for women.

Barriers to implementation and scale-up of self-care interventions

Human systems, including health systems, are hardwired for self-replication; if we do not learn from past mistakes, promising new self-care interventions may suffer the same fate as many other interventions in providing more choice for the few who already enjoy the most, and little to nothing for those who live with the very least. The way health systems have been established has created power hierarchies that disadvantage underserved individuals and communities. Innovations in care largely benefit those living in sociopolitical contexts that support access57. This is particularly relevant for sexual and reproductive health, an area that is too often policed and politicized. For millions of women and girls affected, the restrictions placed on their access and rights to sexual and reproductive health services will influence their negotiation of relationships, will influence their mental, physical, health and well-being, and will impact their agency and choices throughout their lives58. The combination of increasing numbers of people living in multidimensional poverty and the deeply personal nature of sexual and reproductive health calls for a need to improve equitable access to quality products, information and services as key to creating well-functioning, people-centered health systems.

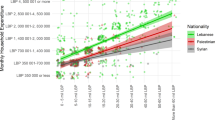

Costs to users of self-care interventions

If costs to users are considered, including out-of-pocket expenditures, financial protection schemes for self-care interventions can improve equity and efficiency59. In Malawi, for instance, people who self-tested for HIV did not incur financial costs, did not need a family member to accompany them and did not need to take time off work60. However, there are a range of out-of-pocket costs to meet the self-care needs of women that are often not factored in health systems’ approaches. This includes the costs of purchasing menstrual management products, including single-use pads, tampons or menstrual cups61,62. In some instances, provider payment systems, which tend to follow a fee-for-service structure, are likely to directly disincentivize the uptake of self-care interventions. However, individual providers and professional associations can enable the introduction and promotion of self-care technologies if they consider these tools as valuable and non-harmful for clients63.

Failure to promote women-initiated methods

Voluntary use of contraception is a crucial enabler of women’s reproductive rights. Women’s contraceptive choices are complex, changing and multifactorial and, in turn, decision-making involves trade-offs among different available options. Self-care interventions such as home pregnancy tests and self-management of medical abortion with mifepristone/misoprostol (where legal) have been successfully adopted in certain settings64.Other practices, despite demonstrating efficacy, have not been successfully taken up and used widely. The female condom is an example of a product that has not benefited from strategic and sustained introduction, donor support, marketing and financing programs65 (Box 3). In 2015, female condoms made up only 1.6% of total global condom distribution, despite being at least equal to the male condom in protecting against unintended pregnancy and STIs, including HIV, and furthermore contributing to women’s sense of empowerment, especially if supported by education and information66,67,68,69,70.

Health and care workers play a key role in ensuring access to interventions, such as emergency contraception. All women and girls at risk of an unintended pregnancy have a right to access emergency contraception, and these methods should be routinely included in all national family planning programs71. During the past decade, there has been a rise in inclusion of emergency contraceptives on national essential medicine lists64, but policies supporting access are uneven. Surveys of providers in India, Nigeria and Senegal indicated that substantial gaps exist in attitudes to, and knowledge of, emergency contraception72,73; for example, the majority of respondents were in favor of requiring a prescription to access emergency contraception and many opposed advanced provision. The survey also found considerable variability in providers’ access to information and training on emergency contraceptive pills. Detrimental practices include providers withholding information about emergency contraception or even refusing to provide it. Such refusals obstruct women’s rights to receive complete information about contraceptives and access to interventions and highlight the need for additional training and sensitization of service providers, as well as supportive policies.

Stigma affecting women’s health decision-making

Social processes of devaluation and exclusion reduce access to resources, power and opportunities, including reducing access to, and engagement with, health systems, services and supplies74. Offering choice in health decision-making that is free of coercion, violence, stigma, discrimination and undue social interference is critical for improved health outcomes.

Stigma towards certain communities of marginalized women, such as those experiencing homelessness, is especially acute at individual, structural and institutional levels75. Some drop-in centers provide only a few menstrual pads at a time, requiring women to make repeated trips during menstruation76. If an adolescent girl wants to access a pregnancy test, she may fear devaluation, judgement and blame for being a sexually active young person. Stigma by health workers toward young and/or unmarried women can include confidentiality breaches in a small community77. A pregnancy self-test may help to mitigate health-care stigma, yet an adolescent girl would still need to purchase the kit and could experience enacted stigma in a pharmacy or other place of access. If the pregnancy test is positive, this would similarly require considerations of anticipated and enacted stigma from family, friends, a community or partner, and even structural stigma if she is not allowed to continue secondary schooling due to pregnancy78.

Furthermore, stigma does not stop at adolescence. From perimenopause to menopause, when the end of a woman’s reproductive cycle can usher in night sweats, hot flashes, insomnia, hair loss, anxiety, heavy bleeding and low sex drive, self-care interventions such as lubricant use for vaginal dryness can be beneficial. However, a lack of awareness and stigma around menopause and sexual health of older women can lead to poor quality care. This can include an unwillingness of health insurance companies to cover costs of lubricants, that could both enhance healthy sexuality and prevent urinary tract infections79,80.

Power inequities limiting self-care options for women

Applying an intersectional approach is critical to understanding how power inequities shape women’s experiences with self-care, including but not limited to gender equity in sexual relationships, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, sex work and disability status81. To illustrate, power equity in sexual relationships is a key consideration for women’s self-care engagement: even after having received training for female condom use, women were not always able to negotiate its use with male sexual partners82. Sexual relationship power equity is linked with both increased condom use and reduced exposure to violence among women; thus, the intersecting social categories that can increase or reduce this relationship equity are important to consider when promoting self-care practices and interventions to women83,84.

Contexts that criminalize identities and practices also shape the ability of women to use self-care and constrain their sexual relationship power equity. In contexts where sex work is criminalized, evidence shows reduced condom negotiation power and reduced ability to carry condoms—exacerbated for female migrant, transgender and sex workers who use drugs85. In the United States, abortion access has been described as a racial justice issue, with racialized minorities less likely to be able to access abortion services from clinics. Survey findings from 7,022 women in the United States reveal that non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women were more likely than non-Hispanic white women to have attempted abortion self-management, as were people living below the federal poverty line; reasons for use included ease, speed and the clinic being too expensive86,87,88. These examples reveal the complexities of implementing evidence-based, effective self-care interventions. In some cases, inequitable gender norms in relationships are key barriers or facilitators for self-care (for example, condom use), while in others, racial and economic disparities in health clinic access may render self-care strategies an approach to mitigate these barriers (for example, self-management of medical abortion).

Self-care interventions for women hold the potential to disrupt inequitable power relations and lift up dignity for those denied it. Science and evidence support the use of many self-care interventions as viable, safe options for women. To reduce the challenges to access, uptake and use of self-care interventions, explicit attention must be paid to ensure appropriate policies, enabling environments and greater justice as much as greater health outcomes.

Attitude of health workers affects women’s ability to self-care

Self-care is first and foremost an issue of personal agency and empowerment, with interconnected gender and cultural considerations89. Practices of health workers or health decision-makers to either directly inhibit or interfere with effective self-care behaviors occur in areas such as the disclosure of health information or limiting the health-care skills of clients and patients in order to maintain professional control and dependency of women on services. The right of women to practice self-care is irrespective of the economic interests of health professionals. This includes the right to access appropriate technologies and information, which are effective and inexpensive. Amending the way the health workforce views its mandate requires interventions such as competency-based training, to equip health and care workers with the skills and capacity to support self-care interventions90,91,92,93.

Integrating self-care interventions within current health systems

A health system comprises the organizations, institutions, resources and people whose primary purpose is to improve health, reflected in the the WHO health system building blocks94 (Fig. 2). These building blocks are recognized as interdependent and overlapping, coming together to produce four key health system outcomes: better and more equitable health outcomes, more responsive services, social and financial risk protection, and improved efficiency. A mature monitoring framework, with indicators for each of the blocks, is used by countries to assess their health systems95 and has been widely used to evaluate health system performance, plan investments, make strategic plans and appraise governance.

Individuals’ self-care practices, their capacities to implement these, and the commodities, environment and accountability structures that support these behaviors are critical components of this system but have been consistently undervalued. Despite enormous potential and the fact that most care is provided in the home, self-care remains a neglected element of the health system95. Self-care interventions must be an adjunct to, rather than a replacement for, direct interaction with the health system. This may require that the boundaries of the health system be reconceptualized if we are to realize the potential of self-care strategies for health improvement, rights and equity.

The role of social support and carers

Caregiving is at the intersection of many challenges, including the following: gender roles, duties and expectations; cultural norms and power dynamics; lack of caregiving role models; physical labor; mental health and mental labor; emotional labor; time pressure; poverty; the learning and use of new skills and tools; tension between the identity and the role (caregiver is not who you are but a role you step in and out of—one needs to explore reflexivity, self-awareness, understanding one’s purpose); and the need to take time for self-care without feeling guilty or selfish. If all unpaid caregiving was paid at minimum wage, this would account for $11 trillion per year or 9% of global GDP96. Most caregivers, formal and informal, are women, and women can positively influence self-care practices by monitoring and facilitating adherence to medications and diet97. The societal pressures to take on this role can nevertheless affect women’s own ability to self-care and can cause mental and physical strain98. For instance, when women combine their role as carers for a member of their family with employment, they often have on the average less free time for their own self-care per day. Health systems must recognize and sustain the role of social support and carers, and the importance of self-care actions in both health maintenance and in coping with ill health99.

Paths to policy objectives

Public policies in support of self-care must function to demystify healthcare, creating enabling environments in which people can more readily promote their health and care for themselves during illness. This implies that the distribution of resources to health-care systems must be altered from excessive concentration of disease-oriented, specialized, often expensive and health system-based approaches to healthcare, toward systems that provide more information and transfer of skills to the clients and patients.

Many policy objectives can be strengthened through support to self-care, including harnessing its health and well-being benefits, limiting overmedicalization100, and protecting constituencies against misinformation and harmful or exploitative practices101. These steps are not uniquely about allocation of resources to health systems. Support of self-care also has systemic implications. Equipping women with better skills, confidence and agency for self-care shifts control of care from health workers to individuals. Therefore, allocation of resources to sectors of education, social services, housing and income maintenance is also needed—which can all contribute to supporting and strengthening of self-care skills.

Regulatory considerations

Drugs with specific pharmacological action, such as nicotine preparations for cessation of smoking, have been successfully reclassified from prescription-only to non-prescription status in many countries. Increasing the availability of more self-care options would require amendments to existing national regulations or facilitating new ones, including, for example, development of over-the-counter availability of contraceptives. A review of 30 globally diverse countries to assess national regulatory procedures for reclassifying prescription-only contraceptives as over-the-counter contraceptives showed that only 43% had formal regulatory procedures in place for a change from prescription-only to over-the-counter status102. Regulatory assessment of a change from prescription to non-prescription status should be based on medical and scientific data on safety and efficacy of the compound and rationality in terms of public health103.

Conclusion

Self-care interventions for women can help disrupt, transform and realign access to health options that complement, but do not replace, facility-based care. Healthcare delivered through health and care workers remains a key component of the human right to health, but for the reasons outlined in this paper, self-care interventions play an important role in the attainment of good health for women. To counter replication of the same discriminations that blight healthcare more broadly, the implementation of self-care interventions demands that the public health sector focus not only on quality care but also on equitable access to care, inclusive of all people. To fulfill their potential, benefit women and advance their health and well-being outcomes, self-care interventions must be centered squarely on people as holders of universal human rights. And for that we should all be held accountable.

References

World Health Organization and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: 2023 global monitoring report. World Health Organization https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240080379 (2023).

World Health Organization. Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context: interim guidance, 1 June 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-essential_health_services-2020.2 (2020).

World Health Organization. WHO guideline on self-care interventions for health and well-being, 2022 revision. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240052192 (2022).

Aujla, M. & Narasimhan, M. The cycling of self-care through history. Lancet 402, 2066–2067 (2023).

World Health Organization. WHO fact sheet on self-care interventions. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/self-care-health-interventions (30 June 2022).

Moreira L. Health literacy for people-centred care: Where do OECD countries stand? OECD Health Working Papers Vol. 107, report no. 107 (2018); https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-literacy-for-people-centred-care_d8494d3a-en

World Health Organization. The world health report 2008: primary health care now more than ever. PAHO https://www.paho.org/en/documents/world-health-report-2008-phc-now-more-ever (2008).

World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/155002 (2015).

World Health Organization. Framework on integrated, people-centered health services. Report to the secretariat. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA69/A69_39-en.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (15 April 2016).

Narasimhan, M., Allotey, P. & Hardon, A. Self care interventions to advance health and wellbeing: a conceptual framework to inform normative guidance. Br. Med. J. 365, l688 (2019).

United Nations Population Fund. Women’s Ability to Decide. Issue Brief on Indicator 5.6.1 of the Sustainable Development Goals. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/resource-pdf/20-033_SDG561-IssueBrief-v4.1.pdf (February 2020).

Starrs, A. M. et al. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet 391, 2642–2692 (2018).

Narasimhan, M., Karna, P., Ojo, O., Perera, D. & Gilmore K. Self-care interventions and universal health coverage. Bull. World Health Organ. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.23.290927 (2024).

Adu, J. et al. Expanding access to early medical abortion services in Ghana with telemedicine: findings from a pilot evaluation. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 31, 2250621 (2023).

Narasimhan, M. et al. Self-care interventions for advancing sexual and reproductive health and rights—implementation considerations. J. Glob. Health Rep. 7, e2023034 (2023).

Taylor S. J. C. et al. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS—Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions. Health Services and Delivery Research No. 2.53 (2014); http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK263840/

Lean, M. et al. Self-management interventions for people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 214, 260–268 (2019).

Mehraeen, E., Hayati, B., Saeidi, S., Heydari, M. & Seyedalinaghi, S. Self-care instructions for people not requiring hospitalization for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/archcid/articles/102978.html (2020).

Riegel, B. et al. Self‐care for the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. J. Am. Heart Assoc. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006997 (2017).

World Health Organization. Classification of self-care interventions for health: a shared language to describe the uses of self-care interventions, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240039469 (12 December 2021).

Wenger, N. K., Hayes, S. N., Pepine, C. J. & Roberts, W. C. Cardiovascular care for women: the 10-Q Report and beyond. Am. J. Cardiol. 112, S2 (2013).

Brown, M. C. et al. Cardiovascular disease risk in women with pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 28, 1–19 (2013).

Godfrey, K. M. et al. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5, 53–64 (2017).

Hopkins, S. A. & Cutfield, W. S. Exercise in pregnancy: weighing up the long-term impact on the next generation. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 39, 120–127 (2011).

Rees, K. et al. Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, CD002128 (2013).

Attree, P. Low-income mothers, nutrition and health: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Matern. Child Nutr. 1, 227–240 (2005).

Bayliss, E. A., Steiner, J. F., Fernald, D. H., Crane, L. A. & Main, D. S. Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann. Fam. Med. 1, 15–21 (2003).

Liddy, C., Blazkho, V. & Mill, K. Challenges of self-management when living with multiple chronic conditions systematic review of the qualitative literature. Can. Fam. Physician. 60, 1123–1133 (2014).

Dickson, V. V., Buck, H. & Riegel, B. Multiple comorbid conditions challenge heart failure self-care by decreasing self-efficacy. Nurs. Res. 62, 2–9 (2013).

Strachan, P. H., Currie, K., Harkness, K., Spaling, M. & Clark, A. M. Context matters in HF self-care: a qualitative systematic review. J. Card. Fail. 20, 448–455 (2014).

Cover, J. et al. Continuation of injectable contraception when self-injected vs. administered by a facility-based health worker: a nonrandomized, prospective cohort study in Uganda. Contraception 98, 383–388 (2018).

Burke, H. M. et al. Effect of self-administration versus provider-administered injection of subcutaneous depot medroxyprogesterone acetate on continuation rates in Malawi: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e568–e578 (2018).

Cover, J., Ba, M., Drake, J. K. & NDiaye, M. D. Continuation of self-injected versus provider-administered contraception in Senegal: a nonrandomized, prospective cohort study. Contraception 99, 137–141 (2019).

Kohn, J. E. et al. Increased 1-year continuation of DMPA among women randomized to self-administration: results from a randomized controlled trial at Planned Parenthood. Contraception 97, 198–204 (2018).

Di Giorgio, L. et al. Is contraceptive self-injection cost-effective compared to contraceptive injections from facility-based health workers? Evidence from Uganda. Contraception 98, 396–404 (2018).

Mvundura, M. et al. Cost-effectiveness of self-injected DMPA-SC compared with health-worker-injected DMPA-IM in Senegal. Contracept. X 1, 100012 (2019).

Ali, G. et al. Perspectives on DMPA-SC for self-injection among adolescents with unmet need for contraception in Malawi. Front. Glob. Womens Health 4, 1059408 (2023).

Corneliess, C., Cover, J., Secor, A., Namagembe, A. & Walugembe, F. Adolescent and youth experiences with contraceptive self-injection in Uganda: results from the Uganda self-injection best practices project. J. Adolesc. Health 72, 80–87 (2023).

The Clinton Health Access Initiative and the Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition. 2023 Family Planning Market Report. Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition https://www.rhsupplies.org/news-events/news/the-clinton-health-access-initiative-chai-and-reproductive-health-supplies-coalition-rhsc-release-the-2023-family-planning-market-report-1838/ (7 December 2023);

Corneliess, C. et al. Education as an enabler, not a requirement: ensuring access to self-care options for all. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 29, 2040776 (2021).

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. In Danger: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. UNAIDS https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2022/in-danger-global-aids-update (27 July 2022).

de Oliveira, T. et al. Transmission networks and risk of HIV infection in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a community-wide phylogenetic study. Lancet HIV 4, e41–e50 (2017).

Abdool Karim, Q. & Abdool Karim, Q. Enhancing HIV prevention with injectable PrEP. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 652–653 (2021).

Karim, Q. A. et al. Women for science and science for women: gaps, challenges and opportunities towards optimizing pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention. Front. Immunol. 13, 1055042 (2022).

Asare, K. et al. Impact of point-of-care testing on the management of sexually transmitted infections in South Africa: evidence from the HVTN702 human immunodeficiency virus vaccine trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 881–889 (2023).

Garrett, N. et al. Impact of point-of-care testing and treatment of sexually transmitted infections and bacterial vaginosis on genital tract inflammatory cytokines in a cohort of young South African women. Sex. Transm. Infect. 97, 555–565 (2021).

Logie, C. H. et al. Self care interventions could advance sexual and reproductive health in humanitarian settings. Br. Med. J. 365, l1083 (2019).

Logie, C. H. et al. Findings from the Tushirikiane mobile health (mHealth) HIV self-testing pragmatic trial with refugee adolescents and youth living in informal settlements in Kampala, Uganda. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 26, e26185 (2023).

Mansoor, L. E. et al. Prospective study of oral pre‐exposure prophylaxis initiation and adherence among young women in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 25, e25957 (2022).

Heck, C. J. & Abdool Karim, Q. Enhancing oral PrEP uptake among adolescent girls and young women in Africa. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 25, e25876 (2022).

Naidoo, N. et al. Fidelity of HIV programme implementation by community health workers in rural Mopani district, South Africa: a community survey. BMC Public Health 18, 1099 (2018).

Zachariah, R. et al. Community support is associated with better antiretroviral treatment outcomes in a resource-limited rural district in Malawi. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101, 79–84 (2007).

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services, 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-155058-1 (1 December 2019).

Drain, P. K. et al. Point-of-care HIV viral load testing: an essential tool for a sustainable global HIV/AIDS response. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00097-18 (2019).

Ngure, K. et al. Efficiency of 6-month PrEP dispensing with HIV self-testing in Kenya: an open-label, randomised, non-inferiority, implementation trial. Lancet HIV 9, e464–e473 (2022).

Mcinziba, A. et al. Perspectives of people living with HIV and health workers about a point-of-care adherence assay: a qualitative study on acceptability. AIDS care 35, 1628–1634 (2023).

Hart, J. T. The inverse care law. Lancet 1, 405–412 (1971).

Ghebreyesus T. A., Allotey P., Narasimhan M. Advancing the ‘sexual’ in sexual and reproductive health and rights: a global health, gender equality and human rights imperative. Bull. World Health Organ. 102, 77–78 (2024).

Remme, M. et al. Self care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights: costs, benefits, and financing. Br. Med. J. 365, l1228 (2019).

Maheswaran, H. et al. Cost and quality of life analysis of HIV self-testing and facility-based HIV testing and counselling in Blantyre, Malawi. BMC Med. 14, 34 (2016).

Babagoli, M. A. et al. Cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analyses of providing menstrual cups and sanitary pads to schoolgirls in Rural Kenya. Womens Health Rep. 3, 773–784 (2022).

Wilson, R. The cost of a period: the SDGs and period poverty. SDG Knowledge Hub https://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/generation-2030/the-cost-of-a-period-the-sdgs-and-period-poverty/ (12 January 2022).

World Health Organization. World Health Organization/United Nations University International Institute for Global Health meeting on economic and financing considerations of self-care interventions for sexual and reproductive health and rights: United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, 2–3 April 2019, summary report. https://www.rhsupplies.org/uploads/tx_rhscpublications/Economic_and_financing_considerations.pdf (2019).

USAID Global Health Supply Chain Program. Contraceptive Security Indicators Survey. https://www.ghsupplychain.org/csi-dashboard/2021 (2021).

United Nations Population Fund & PATH. Female condom: a powerful tool for protection. https://www.unfpa.org/publications/female-condom-powerful-tool-protection (1 January 2006).

World Health Organization & UNAIDS. The female condom: a guide for planning and programming. https://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub01/jc301-femcondguide_en.pdf (1997).

Macaluso, M. et al. Efficacy of the male latex condom and of the female polyurethane condom as barriers to semen during intercourse: a randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Epidemiol. 166, 88–96 (2007).

Farr, G. et al. Contraceptive efficacy and acceptability of the female condom. Am. J. Public Health 84, 1960–1964 (1994).

Vijayakumar, G., Mabude, Z., Smit, J., Beksinska, M. & Lurie, M. A review of female-condom effectiveness: patterns of use and impact on protected sex acts and STI incidence. Int. J. STD AIDS 17, 652–659 (2006).

Fasehun, L. K. et al. Barriers and facilitators to acceptability of the female condom in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Ann. Glob. Health 88, 20 (2022).

World Health Organization. Ensuring human rights within contraceptive programmes: a human rights analysis of existing quantitative indicators. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241507493 (13 June 2014).

Ahonsi, B. A. O., Ishaku, S. M., Idowu, A., & Oginni, A. Providers’ and key opinion leaders’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding emergency contraception in Nigeria. Final survey report. (Population Council, 2012).

Brady, M. et al. Providers’ and key opinion leaders’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices concerning emergency contraception: a multicountry study in India, Nigeria, and Senegal,’ program brief. Final survey report. (Population Council, 2012)

Stangl, A. L. et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 17, 31–31 (2019).

Hopkins, J. & Narasimhan, M. Access to self-care interventions can improve health outcomes for people experiencing homelessness. Br. Med. J. 376, e068700 (2022).

Mathieu, E. Periods an extra hardship for homeless women. Toronto Star https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2017/01/23/periods-anextra-hardship-for-homeless-women.html (23 January 2017).

Maly C., et al. Perceptions of adolescent pregnancy among teenage girls in Rakai, Uganda. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617720555 (2017).

Sobngwi-Tambekou, J. L. et al. Teenage childbearing and school dropout in a sample of 18,791 single mothers in Cameroon. Reprod. Health 19, 10 (2022).

Lusti-Narasimhan, M. & Beard, J. R. Sexual health in older women. Bull. World Health Organ. 91, 707–709 (2013).

The Augustus A. White III Institute. How the stigma of menopause and aging affect women’s experiences. https://aawinstitute.org/2023/01/18/how-the-stigma-of-menopause-and-aging-affect-womens-experiences/ (18 January 2023).

Schuyler, A. C. et al. Building young women’s knowledge and skills in female condom use: lessons learned from a South African intervention. Health Educ. Res. 31, 260–272 (2016).

Bowleg, L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am. J. Public Health 102, 1267–1273 (2012).

Closson, K. et al. Sexual relationship power equity is associated with consistent condom use and fewer experiences of recent violence among women living with HIV in Canada. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000003008 (2022).

Closson, K. et al. Gender, power, and health: measuring and assessing sexual relationship power equity among young sub-Saharan African women and men, a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 23, 920–937 (2022).

Platt, L. et al. Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 15, e1002680 (2018).

Kozhimannil, K. B., Hassan, A. & Hardeman, R. R. Abortion access as a racial justice issue. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1537–1539 (2022).

Redd, S. K. et al. Racial/ethnic and educational inequities in restrictive abortion policy variation and adverse birth outcomes in the United States. BMC Health Serv. Res. 21, 1139 (2021).

Ralph, L. et al. Prevalence of self-managed abortion among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2029245 (2020).

Sen, G. & Mukherjee, A. No empowerment without rights, no rights without politics: gender-equality, MDGs and the post-2015 development agenda. J. Hum. Dev. Capab. 15, 188–202 (2014).

Narasimhan, M., Aujla, M., Van Lerberghe, W. & Elsevier, B. V. Self-care interventions and practices as essential approaches to strengthening health-care delivery. Lancet Glob. Health 11, e21–e22 (2023).

World Health Organization. Self-care competency framework. Volume 1. Global competency standards for health and care workers to support people’s self-care. (WHO, 2023) Self-care competency framework (accessed 02 October 2023); https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240077423

World Health Organization. Self-care competency framework. Volume 2. Knowledge guide for health and care workers to support people’s self-care. (WHO, 2023) Self-care competency framework (accessed 02 October 2023); https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077447

World Health Organization. Self-care competency framework. Volume 3. Curriculum guide for health and care workers to support people’s self-care. (WHO, 2023) Self-care competency framework (accessed 02 October 2023); https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240077461

World Health Organization. Everybody’s business - strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. (WHO, 2007) http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf

World Health Organization. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health systems: a Handbook of Indicators and their Measurement Strategies 1–22 (WHO, 2010).

Addati, L., Cattaneo, U., Esquivel, V. & Valarino, I. Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. International Labour Organization https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_633135/lang--en/index.htm (28 June 2018).

Buck, H. G. et al. Caregivers’ contributions to heart failure self-care: a systematic review. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 14, 79–89 (2015).

Sharma, N., Chakrabarti, S. & Grover, S. Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World J. Psychiatry 6, 7–17 (2016).

World Health Organization. Declaration of Astana (WHO, 2018); https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf

Dowrick, C. & Frances, A. Medicalising unhappiness: new classification of depression risks more patients being put on drug treatment from which they will not benefit. Br. Med. J. 347, f7140–f7140 (2013).

World Health Organization. Infodemic management: an overview of infodemic management during COVID-19, January 2020–May 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/346652 (2021).

Ammerdorffer, A. et al. Reclassifying contraceptives as over-the-counter medicines to improve access. Bull. World Health Organ. 100, 503–510 (2022).

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the regulatory assessment of medicinal products for use in self-medication. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/66154 (2000).

Yeh, P. T. et al. Should home-based ovulation predictor kits be offered as an additional approach for fertility management for women and couples desiring pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001403 (2019).

Yeh, P. T. et al. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels among pregnant individuals with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Glob. Womens Health 4, 1006041 (2023).

Johnson, C. C. et al. Examining the effects of HIV self-testing compared to standard HIV testing services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 20, 21594 (2017).

Ogale, Y., Yeh, P. T., Kennedy, C. E., Toskin, I. & Narasimhan, M. Self-collection of samples as an additional approach to deliver testing services for sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001349 (2019).

Kennedy, C. E., Yeh, P. T., Gaffield, M. L., Brady, M. & Narasimhan, M. Self-administration of injectable contraception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001350 (2019).

Yeh, P. T., Kennedy, C. E., de Vuyst, H. & Narasimhan, M. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus (HPV) testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Glob. Health 4, e001351 (2019).

World Health Organization. Condoms. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/condoms (12 February 2024).

Kennedy, C. E., Yeh, P. T., Gholbzouri, K. & Narasimhan, M. Self-testing for pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 12, e054120 (2022).

Kennedy, C. E., Yeh, P. T., Li, J., Gonsalves, L. & Narasimhan, M. Lubricants for the promotion of sexual health and well-being: a systematic review. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 29, 2044198 (2021).

Atkins, K., Kennedy, C. E., Yeh, P. T. & Narasimhan, M. Over-the-counter provision of emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. BMJ Open 12, e054122 (2022).

King, S. E. et al. Self-management of iron and folic acid supplementation during pre-pregnancy, pregnancy and postnatal periods: a systematic review. BMJ Glob. Health 6, e005531 (2021).

Robinson, J. L. et al. Interventions to address unequal gender and power relations and improve self-efficacy and empowerment for sexual and reproductive health decision-making for women living with HIV: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 12, e0180699 (2017).

Yeh, P. T. et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure among women with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 22, 454 (2022).

PATH. DMPA-SC country data dashboard. DMPA-SC Resource Library https://fpoptions.org/resource/dmpa-sc-country-data-dashboard/ (August 2020).

Cover, J. et al. Contraceptive self-injection through routine service delivery: experiences of Ugandan women in the public health system. Front. Glob. Womens Health 3, 911107 (2022).

World Health Organization. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Research (SRH). https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research-(srh)/human-reproduction-programme (accessed 2 October 2023).

Thomsen, S. C. et al. A prospective study assessing the effects of introducing the female condom in a sex worker population in Mombasa, Kenya. Sex. Transm. Infect. 82, 397–402 (2006).

The female condom: still an underused prevention tool. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, 343 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The named authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this publication and do not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the WHO nor the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEF-WHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Karen O’Leary, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Narasimhan, M., Hargreaves, J.R., Logie, C.H. et al. Self-care interventions for women’s health and well-being. Nat Med 30, 660–669 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02844-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-024-02844-8