Abstract

This study empirically investigates the linkage between boardroom independence and the financial performance of non-financial firms in an emerging market featured by family-controlled businesses and concentrated ownership. The relationship is tested in a sample of 152 non-financial firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange over a period from 2003 to 2018. Firms’ financial performance is measured through return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), market-to-book ratio (MBR), and Tobin’s Q (TQ), while boardroom independence is measured through the proportion of non-executive directors on the corporate board. Using the dynamic GMM approach to address the possibility of endogeneity, it was found that boardroom independence is significantly negatively related to the financial performance of the sample firms. This negative impact is due to the reason of close ties of outside independent directors (non-executive directors) with dominant shareholders and management in personal, financial, and social terms. A significant negative influence of the board size and CEO duality on firms’ financial performance was also observed. The present study will add to the existing literature on corporate governance and firm financial performance using firm-level manually collected data. Further, our findings will also help the policymakers by providing empirical insights for strengthening corporate governance mechanisms in emerging market economies, specifically in the context of Pakistan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corporate governance refers to the rules, regulations, and procedures through which businesses are directed and controlled by their board of directors and management. Prior studies of corporate governance highlighted that the board of directors is an integral part of the internal corporate governance mechanism. It executes the function of supervision of management, protecting shareholder’s rights, and arranging necessary resources for the firm’s operations. The key role of board members is to supervise and monitor managerial behavior and firm performance.

Boardroom independence refers to the proportion of independent directors on the board. Independent directors are professionals who have no direct relation with the firm, so they are likely to look into the managers’ decisions and protect the rights of the shareholders. Decisions made by independent directors on financial investments are, therefore, more rational than those made by managers and shareholders (Zahra and Pearce, 1989). Independent directors usually care about all the stakeholders, given that most firms are less likely to share useful information with all their stakeholders (Ibrahim and Angelidis, 1995). Additionally, independent directors are more interested in reducing the entrenchment behavior of the managers. Thus, independent directors are expected to be more objective and independent in assessing the firm’s investment decisions (Sonnenfeld, 1981). The agency theory also argues in the same vein that a high proportion of independent directors on the board is more effective in governing and controlling management decisions (Fama and Jensen, 1983; Fernández-Gago et al., 2016; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Jizi et al., 2014).

Boardroom independence is the primary and important domain of good corporate governance practices across the globe. Boardroom independence plays a vibrant role in the alignment of shareholders’ interests with those of the management. The significance of outside independent directors in the boardroom got more attention from policymakers, regulators, academicians, and corporate managers after some major corporate failures took place in both developed and developing markets. For example, the failure of Lehman Brothers, American Investment Group, Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing and Merrill Lynch, Adelphi, Seibu China Aviation, Adecco, and Tyco are a few to cite. Furthermore, after the Cadbury (1992) recommendations, boardroom independence and the appointment of non-executive directors on corporate boards became a more popular discussion among academicians and policymakers. The Cadbury Report argues the effectiveness of boardroom independence and the role of non-executive directors in accomplishing good corporate governance in organizations. The report also recommends the presence of at least three outside directors in corporate boardrooms in listed companies.

The provisions of the nomination of outside independent directors (non-executive) on corporate boards are mandatory in both developed and developing countries. Similarly, as an emerging market, Pakistan practices the Anglo-Saxon corporate governance model with a one-tier corporate board prevailing in the listed firms (i.e., the executive and non-executive directors are working under one roof of the organizational layer). The primary focus of the managers and directors is to act as agents to protect and maximize the wealth of the shareholders. The effectiveness of board independence in firm performance in this particular market is, however, less explored.

The key aim of the present study is to explore whether boardroom independence has any impact on a company’s financial performance in the context of Pakistan, an emerging market economy with an inimitable institutional background, ownership concentration, and family-controlled businesses. The role of outside independent directors in firms with concentrated ownership and a family-controlled environment is passive and has a lesser influence on management decisions. Like other emerging economies, Pakistan is a common lawFootnote 1 country and follows the Anglo-Saxon corporate governance model like Canada, New Zealand, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Furthermore, the corporate governance and corporate board practices in Pakistan are similar to “Anglo-Saxon” states such as single-tier board or management board, common laws, family-controlled business, and CEO duality. Like other common law emerging markets, the family representative manager controls the corporate board and proxy non-executive directors. Further, CEO duality is another common phenomenon in the corporate culture of the country. In the family-controlled boardroom, the opinion of the managers and the protection of minor shareholder rights are often a matter of least concern for the companies.

Despite institutional differences, in March 2002, Pakistan issued its first code of corporate governance (hereafter CG 2002) for the companies listed at the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX)Footnote 2.This is considered to be a revolutionary step in the corporate governance reforms of the country. Among other provisions, the CG 2002, places the provision of at least one independent non-executive director on the corporate board of the listed companies. The board independence clause was further tightened in 2012 in the revised code of corporate governance of 2012; introducing a provision that 1/3rd of board members must be outside independent directors. Further, the code was again revised in 2013 thereby introducing a mandatory provision for the nomination of 40 percent outside independent directors (non-executive directors) in the corporate boardroom.

The present study will add to the existing literature by inspecting the link between boardroom independence and financial performance for non-financial companies listed at PSX, an emerging stock market, giving particular attention to endogeneity and heterogeneity concerns. The study uses longitudinal data to mitigate heterogeneity, while the issue of endogeneity is catered for by using the generalized method of moments (GMM) estimators following Adams and Ferreira (2009), Wintoki et al. (2012), and Udin et al. (2017).

The remainder of the study is ordered as follows: Section “Theoretical background, literature review and hypothesis” offers a theoretical and empirical literature review underpinning the proposed hypothesis. The research methodology, data, and sample are discussed in the section “Research and methodology”. Section “Empirical results and discussion” highlights the results and discussion, while the conclusion, policy implications, and future directions are presented in the section “Conclusions and implications”.

Theoretical background, literature review, and hypothesis

In this section, we discuss the theories and empirical literature on boardroom independence and its linkage with a firm’s financial performance.

Agency theory

Agency theory generally advocates the alignment of the interests of owners and agents, delegating power with trust to managers (Jensen and Meckling, 1976). The agency theory speculates that owners employ agents for the shareholder’s wealth maximization. Despite this fact, it is assumed that managers are involved in engaging the self-benefit activities at the cost of shareholder’s wealth. The divergence of the interests of managers and owners creates agency costs, which reduces the efficiency of the business. Moreover, this agency cost will further be observed by the stock market and will negatively influence the stock price of the company. Therefore, if the agency cost is timely identified and managed effectively, it can enhance the efficiency and improve, the share price and overall performance of the company. The agency theory also assumes that the absence of good institutional development and corporate control leads to market failure. Because, in the presence of weak corporate governance practices, parties are involved in incomplete contracts, adverse selection, moral hazards, and asymmetric information, consequently reducing the financial growth of listed companies.

The proponents of agency theory (1983) argue that outside independent directors may reduce agency costs and enhance corporate performance through effective monitoring. The presence of non-executive directors on the board will enhance the stock price of the company (Rosenstein and Wyatt, 1990). Yuetang (2008) finds a positive impact of a high proportion of independent directors on a firm’s financial performance. Moreover, followers of the agency theory posit that the presence of more independent directors on the board will reduce agency and monitoring costs, and restrict the managers’ behavior of pursuing self-benefit, which ultimately improves corporate financial performance. Previous researchers such as Brickley et al. (1994) and Fama and Jensen (1983) supplement the agency theory and argue that outside independent directors play active monitoring roles in corporate decision-making, which enhances a company’s financial performance. Hossain et al. (2001) find a significant positive impact of the proportions of non-executive directors on firm financial performance.

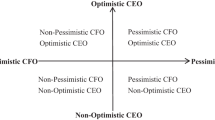

Aggarwal et al. (2007) posit that boardroom independence and positive firm value are closely associated with each other. The responsibility of the executive directors is to look after the daily operations of the company and also to craft and implement long-term business strategies. The inside or executive directors on corporate boards are full-time employees of the company and have close ties with the CEO and CFO of the company. The close ties with company management will lead to passive monitoring of the CEO and CFO’s decisions (Daily and Dalton, 1993). To control the issues arising due to close ties between executive directors, CEO, and CFO, non-executive directors are placed on corporate boards to protect the shareholders’ rights and efficient utilization of organizational resources.

The Cadbury Report (1992) first time highlighted that one of the most important roles of outside directors in listed companies is to monitor the decisions of the CEO and CFO of the company. The Cadbury report recommends that the role of non-executive directors must be independent and that they must be responsible for active monitoring of the management and executive director’s decisions. The effective role played by non-executive directors, when they are actively involved in the strategic formulation of the company, is to closely monitor the decisions of the management.

Stewardship theory

The stewardship theory seeks to resolve the agency conflict that occurs due to a divergence of interest between the agents and principals of the business by focusing boardroom structure, usually executive directors, of the company. The stewardship theory argues that agents/managers are honest stewards for the owners of the firm and perform with dedication. The theory thus suggests that executive directors and managers can achieve firm wealth maximization goals rather than self-interest behavior. Further, the theory also encourages delegating power to managers/ executive directors in strategic decision-making so they can perform better. Moreover, the stewardship theory also argues that managers and executive directors are more concerned about their reputation and career progression, which compels them to work in the interest of shareholders and discourages self-serving behavior.

Supporters of the Stewardship theory also argue that executive board members are trustworthy, and motivated intrinsically to pursue shareholders' wealth maximization. The theory thus also discourages boardroom independence on corporate boards. Moreover, the stakeholder theory emphasizes that the role of executives and board members in an organization is to create maximum value for the stakeholders without compromising their interests. Successful companies manage the interests of stakeholders and align in the direction of the firm’s interests. The theory also posits that business managers use their network and references (with employees, suppliers, and business partners) to efficiently fulfill business tasks.

Similarly, the resource dependency theory supports both stewardship and stakeholder theory and posits that managers and executive directors are valuable assets of the business because their social and business references enhance the firm’s value. The theory also supports the presence of outside directors on the corporate board and argues that outside directors play an important role in establishing a link with other organizations and access to information that can be used for the benefit of the business.

Agrawal and Knoeber (1996) examine the relationship between firm value and board independence and find a negative significant effect of outside directors on the firm’s value. Franks et al. (2001) report that poor-performing companies in the United Kingdom (UK) have a dominance of non-executive directors (outside independent directors) in corporate boardrooms. Similarly, De Jong et al. (2005) report the significant inverse influence of boardroom independence on a business concern’s financial performance. The role of non-executive directors in firms is part-time. Part-time employment limits their role in strategic decision-making (Baysinger and Hoskisson, 1990).

Many earlier studies, inter alia, Koerniadi et al. (2012), Caselli and Gatti (2007), Klein (1998), Yermack (1996), and Hermalin and Weisbach (2001) argue that a board’s efficiency and corporate financial performance decline due to the presence of a higher proportion of independent directors. Coles et al. (2001) find a significant negative impact of outside independent directors on a company’s market value. Shan (2019) finds evidence of a significant negative influence of non-executive directors on a firm’s financial value and supports the stewardship theory. Stewardship theory contends that a corporate board must contain a significant number of inside directors rather than outside directors for effective and efficient decision-making.

Bhagat and Black (2001) study the influence of boardroom independence on an enterprise’s financial value for big US enterprises listed at NYSE (New York Exchange) over the period of 1985–1995. The proportion of non-executive directors on board is used as a proxy for board independence. The study finds evidence of a substantial influence of boardroom independence on a firm’s financial value. Furthermore, the study reports both positive and negative associations between a company’s financial performance and board independence.

Alipour et al. (2019) investigate the moderating effect of board independence on the relationship between financial performance and environmental disclosure quality. They report that board independence positively moderates the association between environmental disclosure and financial performance. Corporate governance practices such as board independence and board size play a vital role in the acquisition decision of the firm.

A significant negative impact of boardroom independence on the company’s value for the companies listed on the Australian Stock Exchange over the period of 2004–2005 is reported. The negative association is due to the institutional environment in Australia, where equity holders restrict the influence of outside directors in corporate affairs. It has been suggested that board independence definition matters to define the association between corporate financial performance and board independence. Many previous studies, for example, Saibaba (2013), Kaur and Gill (2007), Lange and Sahu (2008), Balasubramanian et al. (2010), Chen et al. (2014), García-Ramos and García-Olalla (2014), and Liu et al. (2015) report that firm’s financial performance and boardroom independence are positively related with each other in emerging markets. Similarly, Liu et al. (2015) argue that in government-controlled firms and firms with lower information acquisition and monitoring costs, the degree of board independence is positively related to firm performance. They further argue that the positive relationship between board independence and firm performance in Chinese listed companies is attributed to the self-ability of independent directors to prevent insider trading to improve investment efficiency. Arora and Sharma (2016) report the significant positive influence of boardroom independence, board size, and the intellectual knowledge of board members on a firm’s financial performance. Azeez (2015) found an insignificant linkage between outside directors and the performance of listed companies in Sri Lanka. Rashid (2018) argues the insignificant positive influence of corporate boardroom independence on a company’s financial performance. Further, Weisbach (1988) argues that a company’s CEO can be replaced after reporting poor earnings when the corporate board has a maximum number of non-executive directors. A recent study by Hu et al. (2023) found a positive association between board independence and firm performance during negative demand shocks. The impact of board independence on firm performance also depends upon the appointment of influential and un-influential outside directors (Upadhyay and Öztekin, 2021). Large boards with a high presence of independent and female directors tend to increase firm value, supporting agency, and resource-dependence approaches and are in line with the monitoring or supervising hypothesis.

Furthermore, Koerniadi and Tourani-Rad (2012) find a significant negative association between board independence and financial performance when the independent directors are in the majority on the corporate board and vice versa. A positive association between board independence and firm performance is reprted. Souther (2021) find a positive relationship between board independence and firm value. Further, Thenmozhi and Sasidharan (2020) posit that board independence has a positive impact on the firm value of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in both India and China. They also argue that independent directors play an active monitoring role and the rights of minority shareholders in SOEs.

Al-Gamrh et al. (2020) note that board independence has a weak negative impact on a firm financial and social performance in the context of foreign Arab ownership and the relationship is insignificant in the context of non-Arab foreign ownership. Furthermore, past studies (such as Rashid et al. 2012; Rebeiz, 2018; Singhchawla et al., 2011) and Rashid (2018) find a negative association between board independence and financial performance in emerging markets. Further, Anderson and Reeb (2004) argue that, in the family-controlled business environment, the owners often seek to minimize the presence of independent directors on the corporate board to save the resources of the business. Shan (2019), study the impact of board independence and managerial ownership on the firm’s financial performance. Their study reports a negative significant influence of managers’ shareholdings and boardroom on the firm’s financial value and vice versa. Al-Saidi (2020) found a negative relationship between board independence and firm performance, as proxied by Tobin’s Q. Pham and Nguyen (2020) suggest a negative link between boardroom independence, profitability, and leverage ratio. Potharla and Amirishetty (2021) report an inverted U-shape association between boardroom independence, board size, and financial performance. Zubeltzu-Jaka et al. (2019) investigate the influence of boardroom independence on enterprises’ financial performance through a meta-regression model. The study reports that companies with more independent boards accomplish a higher accounting performance but a lower market performance. They also report that boardroom independence is less effective on return on assets and profitability during market downturns and vice versa. Further, non-executive directors play an efficient role in countries with strong policies for the protection of minority shareholders. Fan et al. (2020) report a significant negative association between outside directors, firm value, and profitability. Board independence may not be beneficial to firm performance without defining the board members’ required qualifications and expertise (Yasser et al., 2017). Hence, boardroom independence may not enhance a company’s financial performance in emerging markets due to its passive monitoring role.

Based on the above discussion and review of previous literature, this study proposes the following main hypothesis in the context of emerging markets, specifically in the case of Pakistani listed companies.

Hypothesis: Boardroom independence is negatively linked with financial performance in emerging markets

Research methodology

Sample and data

This study utilizes a panel data sample consisting of 152 non-financial firms listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (hereafter, PSX) (see footnote 2) over the period of 2003–2018. A total of 367 non-financial companies were listed at PSX during 2018. Initially, we started with 200 non-financial firms, which is approximately 54.49% of the entire population of firms listed on the PSX. The final sample was arrived at after following rigorous selection criteria that required that (i) the sample firm must have data available for a minimum of ten consecutive years, (ii) the sample firm reports corporate governance information, such as the size and breakup of the board and ownership structure, in the annual reports for a minimum of 10 consecutive years and (iii) We excluded firms having missing values over the study sample period. Consequently, we ended up with a final sample comprising 152 non-financial firms that accounted for around 41.41% of total listed non-financial firms at the end of 2018. This resulted in 2280 firm-year observations.

The sample size of the present study is analogous to the earlier studies such as Udin et al. (2017), Akbar et al. (2016), Manzaneque et al. (2016), Shahwan (2015), Wahba (2015), Kamel and Shahwan (2014), Tariq and Abbas (2013), Javid and Iqbal (2010), Javed and Iqbal (2007), and Shaheen and Nishat (2005). The listed non-financial companies showed a growth of 13.57% in size and 9.26% in shareholders’ equity during the year 2018.

Financial data for the study was extracted from the various published reports of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), i.e. Analysis of Financial Statement for non-financial companies (SBP, 2003–2007, 2007–2012, and 2013–2018)Footnote 3, while data on boardroom independence and other corporate governance related variables was manually collected from the annual reports of the sample firms.

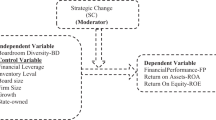

Measurement of the variables

Measurement of financial performance

Following prior studies such as Sanda et al. (2010), Wintoki et al. (2012), Cavaco et al. (2016), Udin et al. (2017), and Rashid (2018), financial performance is measured through four proxies to capture the effect of both the market and accounting financial performance. Market-to-book ratio (MBR) and Tobin’s Q (TQ) are used as proxies for market-based financial performance, while return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE) are used as proxies for accounting financial performance. These proxies are measured as given below;

Measurement of the Board independence

Following previous studies (for example, Faleye, 2015; Rashid, 2018; Wintoki et al., 2012 among others), board independence (BIND) is defined as the proportion of outside to total directors and is measured as follows;

Measurement of control variables

Following the previous literature on corporate governance, this study incorporates Board Size, CEO Duality, Firm Size, Leverage, Growth, Profit Margin, Payout Ratio, and Liquidity Ratio as control variables. The definitions and measurements of these control variables are presented in detail in Table 1.

Model specification and methodology

The objective of this study is to examine the impact of board independence on firm financial performance. To test our hypothesized relationship, we specify the following regression equation.

where

Yit represents the company’s financial performance as proxied by accounting-based performance (i.e. ROA and ROE) and market-based performance (i.e. \(MBR\& \,TQ\)). Moreover, ”i” represents the sample firm \((i=\mathrm{1...146})\) while “t” represents a year in the study sample period \((t=\mathrm{2003...2018})\), ηi, denotes the firm’s unobserved time-variant, while εit represents the composite error term, and μi is used for firm-specific effects. Error term is symbolized by eit. The rest of the variables are explained in sections “Measurement of financial performance ” and “Measurement of the Board Independence”.

It is evident from past studies that corporate governance studies often face the issue of endogeneity and inconsistency of the parameter estimations. Following prior studies such as Demsetz and Villalonga (2001), Antoniou et al. (2008), Nakano and Nguyen (2012), Flannery and Hankins (2013), and Wintoki et al. (2012, we employed the dynamic generalized method of moment (DGMM) estimator to address the issue of endogeneity. The dynamic version of the GMM was applied as the static GMM was not suitable here due to the absence of suitable instrumental variables in the perspective of corporate governance studies and the company’s financial performance. Following the approach of prior studies by Wintoki et al. (2012), Nguyen et al. (2014), and Udin et al. (2017), 1-year lag of the dependent variable (Yit−1) was used for the dynamic adjustment and to resolve the problem of endogeneity.

After this adjustment, Eq. (1) can be expressed as follows:

where Yit−1 denotes the one-year lagged financial performance of the firm i.

Empirical results and discussion

Summary statistics and VIF test

Tables 2 and 3 summarize the descriptive statistics of the variables along with the VIF test for the detection of multi-collinearity between the independent variables. The summary statistics reveal that an average board in our sample firms has around 58% independent directors on the board, with board independence ranging from as low as 9% to as high as 100% of the total board size. This average percentage value of board independence (58%) is well in conformity with the country’s code of corporate governance of 2013 (CG 2103) and international standards, specifically, the Anglo-American standards.

It is worthwhile to note here that the average percentage of board independence in Pakistan is higher than its neighbor emerging markets, with an average of 49% board independence in India and an average of 12% in Bangladesh, for instance, as reported by Mohapatra (2016) and Rashid (2018). Furthermore, the average board independence in Anglo-American countries is 61% in Irish companies, 36% in US companies, and 54% in US large industrial companies (see Brennan and McDermott, 2004; Daily and Dalton, 1997; Yermack, 1996). The average board independence in our sample is also comparable to the recommendations of the Cadbury Report (1992). The Cadbury Report (1992) advocates a minimum of three non-executive (outside) directors on the corporate board, while another report proposes that fifty percent of boardroom (without the board chairman) should be non-executive.

Similarly, the summary statistics in Table 2 also show that the average board size in the sample is eight members, with a minimum of six and a maximum of 16 members. These figures indicate that listed companies at the PSX are following rules prescribed by the country code of corporate governance 2002 and 2013. Further, the average figure of board size for Pakistan is closer to its neighbor emerging markets as well such as Bangladesh and India, where the average number of directors is 6.6–10.5, respectively (see Kalsie and Shrivastav, 2016; Pranati, 2017; Rashid, 2018).

Additionally, around 95% of the CEOs in our sample are dual CEOs, showing that in a majority of the companies listed at the PSX, the same individual holds the title of both the CEO and the chairperson of the corporate board. The Code of Corporate Governance of Pakistan 2013 explicitly restricts CEO duality practices in the listed companies, as the CEO is appointed by the board of directors who also evaluate his performance and ensure a succession plan for the CEO. The average value of 95% CEO duality of our sample companies is much higher than that in Bangladesh and India. CEO duality is 26% in Bangladesh and 28% in India (see Rashid, 2018; Shrivastav and Kalsie, 2016).

As regards the performance indicator variables, the average value of return on asset (ROA) is 6% which ranges between −2.76% to 1.07%. Return on Equity (ROE) has a mean value of 1.32%, with a minimum value of −92.00% and a maximum value of 117.2%, while the average values of Tobin’s Q (TQ) and market-to-book ratio (MBR) are 18% and 12.78%, respectively.

The results of the VIF test are presented in the last column of Table 2, We employed the VIF test to check the multi-collinearity issue among the explanatory variables. The multi-collinearity problem arises when the value of VIF exceeds 10 (Gujarati, 2003). From Table 2, we can observe that the maximum value VIF in the last column of Table 2 (see Appendix) is 1.26 while all the other VIF values are less than the threshold of 10 providing no evidence of multi-collinearity in the variables (see also correlation matrix, Table 3).

Empirical results and discussion

Table 4 presents the empirical results of GMM regressions of board independence and firm financial performance. We employed the Arellano-Bond Serial Correlation AR (1) and AR (2) to check possible homogeneity among the instrumental variables used in the analysis. Further, the J-statistic test was also used for over-identifying restrictions. All the diagnostic tests for the four regressions model are satisfied (shown in the last four rows of Table 4).

Interestingly, the results in Table 4 show a statistically significant inverse relationship between boardroom independence and firms’ financial performance across all four regression models after we controlled for heterogeneity and unobservable firm-level dynamic endogeneity. This reflects that corporate boardroom independence negatively affects financial performance in emerging markets, such as Pakistan. The negative influence of boardroom independence on firm financial growth is also reported in emerging markets like India and Bangladesh (see Kalsie and Shrivastav, 2016; Pranati, 2017; Rashid, 2018). Our results are in line with the results of Sheikh et al. (2013), who report a negative link between boardroom independence and company’s financial value of the non-financial companies listed on the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) over the period of 2003–2018. Moreover, our results are also in line with the results of Ehikioya (2009); Kiel and Nicholson (2003), Coles et al. (2001), Agrawal and Knoeber (2012), Yasser et al. (2017) and Agrawal and Knoeber (1996) who also found a negative association between board independence and firm performance. Our finding is not surprising because in Pakistani listed firms, the independent directors are not truly independent, due to their close relations with company management. They are often family friends who are appointed as proxy non-executive directors. Likewise, in Pakistan, independent directors have close ties with the dominant shareholders in personal, financial, and social terms that may influence their independent judgment, which endangers their role as outside independent directors. Meanwhile, to monitor the opportunistic behavior of the top management and to mitigate the agency problem, more boardroom independence is required, thereby appointing a proportion of outside directors to the corporate board. High boardroom independence is useful for a true and fair disclosure of information to the stakeholders, which can enhance the corporate reputation and financial growth (Zhang, 2012).

The results in Table 4 further show a significant negative association between firms’ financial performance (i.e. TQ & MBR and ROA & ROE) and the firm’s board size. The negative coefficient implies that a larger board size may impede organizational communication and reduce the effectiveness of monitoring by delaying the decision-making process. Moreover, this may also have a connection to the institutional background of the country where a majority of the listed firms are either family-owned or are controlled by business groups, and board members are appointed from the family or family friends without considering their qualifications and relevant experience. In the majority of the cases, proxy/ghost directors are appointed to comply with the requirements of the Securities Exchange of Pakistan (SECP), which might further hurt the true financial performance of the firms.

Further, the Companies Law 1984 and different versions of the codes of corporate governance issued by the SECP from time to time (such as Code 2002, code 2013, and Code 2017) have mandatory provisions regarding board size and board independence. The ideal corporate boardroom independence varies from a minimum of five outside independent directors to a maximum of ten members depending on the operational size and nature of the firms. In listed companies at the PSX, the average board size is eight members (see Table 3).

The current study also observed an insignificant association between CEO duality and ROA but a significant negative association with ROE, MBR, and TQ. One reason for this might be that most of the companies have family-concentrated ownership structures. Further, a significant inverse association between market-based firm performance and CEO duality may be due to the pyramidal and cross-shareholding ownership, control of business groups, and lack of corporate transparency. Further, in most emerging countries such as Pakistan, family members hold the position of CEO and chairperson of the board, and their focus is on short-term benefits and earnings instead of longer-term earnings and shareholder benefits. In such an environment, the common practice of family members/friends holding top management positions is also one of the main reasons for the agency conflict and leads to the negative effect of CEO duality on the company’s financial value. Our finding is consistent with the prediction of the agency theory that uniting both roles (i.e. CEO role and chairperson of the board) into a single position would weaken board control and adversely affect firm financial performance. Further, growth, payout ratio, and firm size were found to be significantly positively related to both market and accounting proxies of firm value (i.e. MBR & TQ and ROA & ROE). We also observed a significant negative impact of the firm’s leverage and liquidity on both the market as well as accounting financial performance. Moreover, we observed a positive significant impact of profit margin on return on assets, while a significantly negative relation with ROE, MBR, and TQ.

Conclusions and implications

This study explored the connection between boardroom independence and firm financial performance in a sample of listed non-financial firms from an emerging market i.e., Pakistan. Using panel data of 152 non-financial companies listed at the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) over the period from 2003 to 2018, the study finds a significant negative impact of boardroom independence on sample firms’ financial performance. This finding is in contrast to the prediction of agency theory and the common belief that the outside (independent) directors will protect and promote shareholders’ wealth due to their legally vested responsibilities. This negative relationship of corporate board independence implies the passive role of independent directors and close ties with the company management. It might be that the non-executive directors are mostly part-timers and lack insider information about the company, which limits their decision-making power and influences the executive/insider directors’ decisions. Our results are consistent with the findings of other studies in emerging markets, for example, in Bangladesh (for instance; Mohapatra, 2016; Rashid, 2018; Rashid et al., 2010, 2012) and India (see Mohapatra, 2016; Pranati, 2017 among others). We also find a significant negative relationship between corporate board independence and financial performance after controlling for firm heterogeneity and dynamic endogeneity. Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that proper re-balancing may be required concerning boardroom independence in the non-financial sector of Pakistan.

In addition to this, we observed a negative effect of CEO duality and board size on the listed company’s financial value. This negative effect of board size and CEO duality on ROE, MBR & TQ confirms that board duality in Pakistani business culture supports CEO entrenchment, reduces the effectiveness of board monitoring, and impedes firm performance.

The implications of this study are multifold: First, we observed a significant negative influence of boardroom independence and a firm’s financial performance. This finding implies that in Pakistan, the outside directors on the board are unable to provide any independent advice and decisions due to their close ties with dominant shareholders and counterparts. We recommend that the SECP introduce clear provisions for the appointment and criteria of independent directors in the code of corporate governance and should introduce mechanisms to ensure boardroom independence and strengthen the monitoring capabilities of board members.

The results of this study contribute to the literature on the connection between boardroom independence and a firm’s financial performance in a South Asian emerging market i.e., Pakistan. The findings of this study may therefore provide reflective insights for tamping up good corporate governance mechanisms in emerging markets, specifically in the context of Pakistan. Future researchers are encouraged to further investigate the impact of outside directors’ characteristics such as gender, background qualifications, financial expertise, and their legitimacy on firm performance. Further, this study can be extended by considering the financial sector and considering other emerging financial markets.

Data availability

Data is hand collected from the annual reports of the sample companies and balance sheet analysis of Joint stock companies. However, data is publicly available via the following links: 1. https://www.sbp.org.pk/reports/annual/FSANFC/Years.htm. 2. https://opendoors.pk/premium-data/financial-statement-data/ (annual reports of the sample companies).

Notes

“ Pakistan has adopted the English common law”

Formally, “Karachi Stock Exchange (KSE)”

“SBP publish 5-year financial statement analysis of joint stock companies.”

References

Adams RB, Ferreira D (2009) Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. J Financ Econ 94(2):291–309

Aggarwal R, Erel I, Stulz RM, Williamson R (2007) Do US firms have the best corporate governance? A cross-country examination of the relation between corporate governance and shareholder wealth”, No. w12819. National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 0898-2937

Agrawal A, Knoeber CR (1996) Firm performance and mechanisms to control agency problems between managers and shareholders. J Financ Quant Anal 31(3):377–397

Agrawal A, Knoeber CR (2012) Corporate governance and firm performance. In: Agrawal A, Knoeber CR (eds) Oxford handbook in managerial economics. Oxford University Press

Akbar S, Poletti-Hughes J, El-Faitouri R, Shah SZA (2016) More on the relationship between corporate governance and firm performance in the UK: evidence from the application of generalized method of moments estimation. Res Int Bus Financ 38:417–429

Al-Gamrh B, Al-Dhamari R, Jalan A, Jahanshahi AA (2020) The impact of board independence and foreign ownership on financial and social performance of firms: evidence from the UAE. J Appl Account Res 21(2):201–229

Alipour M, Ghanbari M, Jamshidinavid B, Taherabadi A (2019) Does board independence moderate the relationship between environmental disclosure quality and performance? Evidence from static and dynamic panel data. Corp Gov: Int J Bus Soc 19(3):580–610. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-06-2018-0196

Al-Saidi M (2020) Board independence and firm performance: evidence from Kuwait. Int J Law Manag 2(63):251–262

Anderson RC, Reeb DM (2004) Board composition: balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Adm Sci Q 49(2):209–237

Antoniou A, Guney Y, Paudyal K (2008) The determinants of capital structure: capital market-oriented versus bank-oriented institutions. J Financ Quant Anal. 43(1):59–92

Arora A, Sharma C (2016) Corporate governance and firm performance in developing countries: evidence from India. Corp Gov 16(2):420–436. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-01-2016-0018

Azeez A (2015) Corporate governance and firm performance: evidence from Sri Lanka. J Financ 3(1):180–189

Balasubramanian N, Black BS, Khanna V (2010) The relation between firm-level corporate governance and market value: a case study of India. Emerg Mark Rev 11(4):319–340

Baysinger B, Hoskisson RE (1990) The composition of boards of directors and strategic control: effects on corporate strategy. Acad Manag Rev 15(1):72–87

Bhagat S, Black B (2001) The non-correlation between board independence and long-term firm performance. J CorP l 27:231

Brennan N, McDermott M (2004) Alternative perspectives on independence of directors. Corp Gov: Int Rev 12(3):325–336

Brickley JA, Coles JL, Terry RL (1994) Outside directors and the adoption of poison pills. J. Financ Econ 35(3):371–390

Cadbury A (1992) The code of best practice. Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance. Gee and Co Ltd., p. 27

Caselli S, Gatti S (2007) Corporate governance and independent directors: much ado about nothing? The evidence behind private equity investment performance. SSRN, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract,9684655

Cavaco S, Challe E, Crifo P, Rebérioux A, Roudaut G (2016) Board independence and operating performance: analysis on (French) company and individual data. Appl Econ 48(52):5093–5105

Chen Q, Hou W, Li W, Wilson C, Wu Z (2014) Family control, regulatory environment, and the growth of entrepreneurial firms: International evidence. Corp Gov: Int Rev 22(2):132–144

Coles JW, McWilliams VB, Sen N (2001) An examination of the relationship of governance mechanisms to performance. J Manag 27(1):23–50

Daily CM, Dalton DR (1993) Board of directors leadership and structure: control and performance implications. Entrep Theory Pract. 17(3):65–81

Daily CM, Dalton DR (1997) Separate, but not independent: board leadership structure in large corporations. Corp Gov: Int Rev 5(3):126–136

De Jong A, DeJong DV, Mertens G, Wasley CE (2005) The role of self-regulation in corporate governance: evidence and implications from the Netherlands. J Corp Financ 11(3):473–503

Demsetz H, Villalonga B (2001) Ownership structure and corporate performance. J Corp Financ 7(3):209–233

Ehikioya BI (2009) Corporate governance structure and firm performance in developing economies: evidence from Nigeria. Corp Gov 9(3):231–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700910964307

Faleye O (2015) The costs of a (nearly) fully independent board. J Empir Financ 32:49–62

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Separation of ownership and control. J Law Econ 26(2):301–325

Fama EF, Jensen MC (1983) Agency problems and residual claims. J Law Econ 26(2):327–349

Fan Y, Jiang Y, Kao M-F, Liu FH (2020) Board independence and firm value: a quasi-natural experiment using Taiwanese data. J Empir Financ 57:71–88

Fernández-Gago R, Cabeza-García L, Nieto M (2016) Corporate social responsibility, board of directors, and firm performance: an analysis of their relationships. Rev Manag Sci 10:85–104

Flannery MJ, Hankins KW (2013) Estimating dynamic panel models in corporate finance. J. Corp Financ 19:1–19

Franks J, Mayer C, Renneboog L (2001) Who disciplines management in poorly performing companies? J Financ Intermed 10(3–4):209–248

García-Ramos R, García-Olalla M (2014) Board independence and firm performance in Southern Europe: a contextual and contingency approach. J Manag Organ 20(3):313–332

Gujarati DN (2003) Basic econometrics, 4th edn. McGraw Hill, United States Military Academy, West Point

Hermalin B, Weisbach M (2001) Boards of Directors as an endogenously determined institution: a survey of the economic literature. NBER working paper

Hossain M, Prevost AK, Rao RP (2001) Corporate governance in New Zealand: the effect of the 1993 Companies Act on the relation between board composition and firm performance. Pac-Basin Financ J 9(2):119–145

Hu X, Lin D, Tosun OK (2023) The effect of board independence on firm performance—new evidence from product market conditions. Eur J Financ 29(4):363–392

Ibrahim NA, Angelidis JP (1995) The corporate social responsiveness orientation of board members: are there differences between inside and outside directors? J Bus Ethics 14:405–410

Javed AY, Iqbal R (2007) Relationship between corporate governance indicators and firm value: a case study of Karachi stock exchange. Working paper 2007:14. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad

Javid AY, Iqbal R (2010) Corporate governance in Pakistan: corporate valuation, ownership and financing. Working paper 2010:57. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics Islamabad

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Corporate Governance (77–132)

Jizi MI, Salama A, Dixon R, Stratling R (2014) Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility disclosure: evidence from the US banking sector. J Bus Ethics 125:601–615

Kalsie A, Shrivastav SM (2016) Analysis of board size and firm performance: evidence from NSE companies using panel data approach. Indian J Corp Gov 9(2):148–172

Kamel H, Shahwan T (2014) The association between disclosure level and cost of capital in an emerging market: evidence from Egypt. Afro-Asian J Financ Account 4(3):203–225

Kaur P, Gill S (2007) The effects of ownership structure on corporate governance and performance: an empirical assessment in India. Research Project NFCG, 2008

Kiel GC, Nicholson GJ (2003) Board composition and corporate performance: how the Australian experience informs contrasting theories of corporate governance. Corp Gov: Int Rev 11(3):189–205

Klein A (1998) Firm performance and board committee structure. J Law Econ 41(1):275–304

Koerniadi H, Rad T, Alireza (2012) Does board independence matter? Evidence from New Zealand. Australas Account Bus Financ J 6(2):3–18

Koerniadi H, Tourani-Rad A (2012) Does board independence matter? Evidence from New Zealand. Australas Account Bus Financ J 6(2):3–18

Lange H, Sahu C (2008) Board structure and size: the impact of changes to Clause 49 in India. U21Global Working Paper Series, No. 004/2008

Liu Y, Miletkov MK, Wei Z, Yang T (2015) Board independence and firm performance in China. J Corp Financ 30:223–244

Manzaneque M, Priego AM, Merino E (2016) Corporate governance effect on financial distress likelihood: evidence from Spain. Rev Contab 19(1):111–121

Mohapatra P (2016) Board independence and firm performance in India. Int J Manag Pract 9(3):317–332

Nakano M, Nguyen P (2012) Board size and corporate risk taking: further evidence from Japan. Corp Gov: Int Rev 20(4):369–387

Nguyen T, Locke S, Reddy K (2014) A dynamic estimation of governance structures and financial performance for Singaporean companies. Econ Model. 40:1–11

Pham HST, Nguyen DT (2020) Debt financing and firm performance: the moderating role of board independence. J Gen Manag 45(3):141–151

Potharla S, Amirishetty B (2021) Non-linear relationship of board size and board independence with firm performance–evidence from India. J Indian Bus Res 13(4):503–532

Pranati M (2017) Board size and firm performance in India. Vilakshan: XIMB J Manag 14(1):19–30

Rashid A (2018) Board independence and firm performance: evidence from Bangladesh. Future Bus J 4(1):34–49

Rashid A, De Zoysa A, Lodh S, Rudkin K (2010) Board composition and firm performance: evidence from Bangladesh. Australas Account Bus Financ J 4(1):76–95

Rashid A, De Zoysa A, Lodh S, Rudkin K (2012) Reply to “Response: board composition and firm performance: evidence from Bangladesh—a sceptical view”. pp. 121-131. https://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/284

Rebeiz KS (2018) Relationship between boardroom independence and corporate performance: reflections and perspectives. Eur Manag J 36(1):83–90

Rosenstein S, Wyatt JG (1990) Outside directors, board independence, and shareholder wealth. J Financ Econ 26(2):175–191

Saibaba MD (2013) Do board independence and CEO duality matter in firm valuation?—An empirical study of Indian companies. IUP J Corp Gov 12(1):50

Sanda AU, Mikailu AS, Garba T (2010) Corporate governance mechanisms and firms’ financial performance in Nigeria. Afro-Asian J Financ Account 2(1):22–39

Shaheen R, Nishat M (2005) Corporate governance and firm performance: an exploratory analysis. Paper presented at the conference of Lahore School of Management Sciences, Lahore

Shahwan TM (2015) The effects of corporate governance on financial performance and financial distress: evidence from Egypt. Corp Gov 15(5):641–662

Shan YG (2019) Managerial ownership, board independence and firm performance. Account Res J 32(2):203–220. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARJ-09-2017-0149

Sheikh NA, Wang Z, Khan S (2013) The impact of internal attributes of corporate governance on firm performance: evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 23(No.1):38–55

Shrivastav SM, Kalsie A (2016) The relationship between CEO duality and firm performance: an analysis using panel data approach. IUP J Corp Gov 15(2)

Singhchawla W, Evans R, Evans J (2011) Board independence, sub-committee independence and firm performance: evidence from Australia. Asia Pac J Econ Bus 15(2):1–15

Sonnenfeld J (1981) Executive apologies for price fixing: role biased perceptions of causality. Acad Manag J 24(1):192–198

Souther ME (2021) Does board independence increase firm value? Evidence from closed-end funds. J Financ Quant Anal 56(1):313–336

Tariq YB, Abbas Z (2013) Compliance and multidimensional firm performance: evaluating the efficacy of rule-based code of corporate governance. Econ Model 35:565–575

Thenmozhi M, Sasidharan A (2020) Does board independence enhance firm value of state-owned enterprises? Evidence from India and China. Eur Bus Rev 22:2730

Udin S, Khan MA, Javid AY (2017) The effects of ownership structure on likelihood of financial distress: an empirical evidence. Corp Gov 17(4):589–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-03-2016-0067

Upadhyay A, Öztekin Ö (2021) What matters more in board independence? Form or substance: evidence from influential CEO-directors. J Corp Financ 71:102099

Wahba H (2015) The joint effect of board characteristics on financial performance. Rev Account Financ 14(1):20–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAF-03-2013-0029

Weisbach MS (1988) Outside directors and CEO succession. J Financ Econ 20(431):60

Wintoki MB, Linck JS, Netter JM (2012) Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J Financ Econ 105(3):581–606

Yasser QR, Mamun AA, Rodrigs M (2017) Impact of board structure on firm performance: evidence from an emerging economy. J Asia Bus Stud 11(2):210–228

Yermack D (1996) Higher market valuation of companies with a small board of directors. J. Financ Econ 40(2):185–211

Yuetang W (2008) Boardas independence, ownership balance and financial information quality. Account Res 1:55–62

Zahra SA, Pearce JA (1989) Boards of directors and corporate financial performance: a review and integrative model. J Manag 15(2):291–334

Zhang L (2012) Board demographic diversity, independence, and corporate social performance. Corp Gov 12:686–700. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720701211275604

Zubeltzu-Jaka E, Ortas E, Alvarez-Etxeberria I (2019) Independent directors and organizational performance: new evidence from a meta-analytic regression analysis. Sustainability 11(24):7121

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Majid Jamal Khan jointly developed and refined the main idea with all the other authors. He developed the theoretical background and contributed to the write-up of the manuscript. Faiza Saleem contributed to the literature review and interpretations of the results for the manuscript. Shahab Ud Din Worked on the empirical and data analysis portions of the manuscript. He is also involved in all the correspondence with the journal and will be looking after any further queries. Muhammad Yar Khan contributed to the collection and refining of data and also helped in data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is not required for this study, as it did not involve the use of human or animal participants. However, all procedures are conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines established by Journal guidelines and ethical principles of the university.

Informed consent

Ethical approval is not required for this study, as it did not involve the use of human or animal participants. However, all procedures are conducted in accordance with ethical principles and guidelines established by Journal guidelines and ethical principles of the university.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, M.J., Saleem, F., Ud Din, S. et al. Nexus between boardroom independence and firm financial performance: evidence from South Asian emerging market. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 590 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02952-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02952-3