Abstract

The need for immediate communication in a world characterized by an ever-increasing flow of information has led to a rapid increase in volunteer translation in recent decades. While previous studies have focused on aspects such as volunteer translators’ motivation and the attendant ethical issues of voluntary translation, comparatively little research has explored the phenomenon from a discursive perspective. The research reported in this article explored the discursive construction of the volunteer translator in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) active in Spain using critical discourse analysis. Drawn from analysis of 25 semi-structured individual interviews with volunteer translators in five different NGOs, the findings reveal that volunteer translators are seen either as an agent and actor of social change who facilitates communication and possesses a strong sense of identity and social status, or as someone who is interfering in a sector traditionally limited to professional translators and who consequently has a weaker sense of identity and social status. This suggests that the role of the volunteer translator currently lacks definition, and that further research is needed to better understand the relationship between volunteer and professional translators in the 21st century.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The social value of volunteers as cultural mediators has increased in recent years due to various crises, most notably the COVID-19 global pandemic, that have shaken societies around the world. The volunteer is an indispensable social and cultural actor who is usually associated with humanitarian aid and contributes to reinforcing democratic values in societies (Ariño Villarroya and Castelló Cogollos 2008). Over the last decade researchers in translation studies have explored various aspects of volunteer translators and their work (Drugan and Tipton 2017; Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva 2012), including personal motivations (Jones 2019; Olohan 2014) and the inclusion of volunteer translation in training contexts (Sánchez Ramos 2021; Tziafa 2019). However, little research to date has focused on the discursive construction of the volunteer translator in order to determine their identity and relationships within society, as has been done for other kinds of volunteers (Friedrich 2019; Kang and Hong 2020; Yap et al. 2011).

Taking critical discourse analysis (CDA) as a starting point (Fairclough 1992, 1995, 2005), in this article we carried out a preliminary research to explore how volunteer translators in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) discursively construct their identities. NGOs are representative of the third sector, which plays a central role in meeting social needs beyond the scope of private organizations or public institutions (Moulaert et al. 2017). We also compare the discursive strategies used by volunteer NGO translators to create their social identity and establish power relations within a multicultural society.

These are the research questions the study explores:

RQ1 To what extent do translator volunteers represent volunteering?

RQ2 What are the ideologies identified in their discourse?

RQ3 To what extent do their discourse legitimate or challenge translator volunteering practice?

The article is structured as follows. The “Volunteering and translation” section provides theoretical context in the form of a review of volunteering and translation. The “Method” section then describes the CDA methodology used to identify the discursive identity of the volunteer NGO translators included in this study. The results of the study are presented and discussed in the “Results and discussion” section, before the final section summarizes our conclusions.

Volunteering and translation

The need for immediate communication in a society characterized by ongoing political and economic change has led to an increase in volunteer translating in contexts that attempt to close social gaps among the most disadvantaged sectors. The volunteer, often called “the good citizen” and considered a key player in society, has been defined as a person who undertakes an altruistic activity (López Franco and Shahrokh 2015). Although several sectors may benefit from the work of volunteers, research generally focuses on the third sector (Moulaert et al. 2017), where volunteering implies a feeling of commitment and responsibility linked to the idea of cooperation with the community (Grönlund 2011).

In the translation studies field, research on volunteer translation has proliferated in recent years (Sánchez Ramos 2021). Olohan (2014: 18) defines volunteer translation as “translation conducted by people exercising their free will to perform translation work which is not remunerated, which is formally organized and for the benefit of others.” Nonetheless, delimiting this concept can be thorny to say the least, as various issues require further analysis, such as those of remuneration (Pym 2011; Snyder and Omoto 2008), the profile of the volunteer (Jiménez-Crespo 2017) or their ethical implications (Basalamah 2020). As pointed out by Jones (2019), volunteer translation has also sparked a debate among professional translators who point to ethical and visibility issues, especially when a wide variety of volunteer roles require no specific training. The amount of digital content to be translated has grown in the last decades since the development of the World Wide Web, which has facilitated the expansion of volunteer translation. Volunteering is usually viewed as unpaid work, which is considered negatively by some but positively by others, in terms of the impact of enhanced access to information for more disadvantaged sectors (Kang and Hong 2020).

As Kang and Hong (2020) point out, another issue relating to volunteer translation are the many different labels used to refer to it, which include community translation (O’Hagan 2011), crowdsourced translation (McDonough Dolmaya 2012); user-generated translation (Perrino 2009), online collaborative translation (Jiménez Crespo 2017), social translation (Desjardins 2017), collaborative translation (Désilets 2007), non-professional translation (Pérez-González and Susam-Saraeva 2012), wiki-translation (Cronin 2010), amateur or volunteer translation (Pym 2011), community-based translation (Anastasiou and Gupta 2011), community, crowdsourced, and collaborative translation (CT3; Ray and Kelly 2011), and online social translation (McDonough and Sánchez Ramos 2019). According to Jones (2019: 12), research into volunteer translation “only emerged as a substantial research interest in the 2000s – although interest in the related translation activism already rose during the cultural turn of the 1990s – with increasing focus being given to online volunteer translation specifically, along with the development of the field itself.”

Studies have since investigated the motivation of volunteers (Cámara de la Fuente 2015; Deriemaeker 2014; Olohan 2014), the inclusion of volunteer translation in training programs (Desjardins 2011; Sánchez Ramos 2019), the attitudes of professionals to collaborative practices (Gough 2011; Läubli and Orrego-Carmona 2017), the final quality of translations performed by volunteers (Carreira Martínez and Pérez Jiménez 2011), and the work of volunteer translators in the third sector (Boéri and Maier 2010; Tesseur 2019). However, few studies have explored the identity of the volunteer translator using methodologies that determine their relationship and position within society, as occurs in other disciplines. Fahey (2005), for instance, aware of the complexity surrounding volunteering in recent years due to social, political, and economic changes, addresses identity and power relations in Australia and New Zealand using CDA and the theories of Foucault (1980, 1991) and Fairclough (1992, 1995, 2005). Applying a similar methodology, although only using Fairclough’s approach, Kang and Hong (2020) analyze the discursive construction of volunteer translators for Coursera, a popular online educational platform, focusing on the ethical issues associated with volunteer translation. As we will see in the next section, this research by Kang and Hong (2020) served as inspiration for our own application of a critical methodology to volunteer translation.

Like Boéri and Maier (2010), we focus on the volunteer translator in the third sector from a humanitarian perspective, where collaboration aims at resolving social problems of individuals or groups of individuals at a higher risk of exclusion and inequality and where translation is a bridge between languages and cultures in favor of the most disadvantaged in society. As underlined by Kang and Hong (2020: 55), “Volunteering is historically a humanistic, as well as a social and political concept, consistent with egalitarian principles, and involving activities that provide potential benefits for both volunteers and service organizations.” Our ultimate objective in this article is to explore the position(s) volunteer translators occupy in society and how their discursive positioning contributes to the construction of their identities.

Method

The research reported here adopted a qualitative approach within the framework of CDA, a methodology developed by Fairclough (1992, 1995, 2005) as a member of the Language, Power and Ideology research group at the University of Lancaster in the United Kingdom. Fairclough’s work is foundational for the study of language from a CDA perspective.

While there is growing research interest in the volunteer translator, few studies focus on analyzing how they discursively construct their identity and the position they occupy in society. We adopt the definition of identity proposed by Grönlund (2011: 855), which is “the sense an individual has of oneself,” comprising “important abilities, roles, values, background, and reference groups.” It is individuals themselves who, through their acts and discourse, construct their own identity (Fairclough 1992).

CDA allows us to analyze power relations between different actors and to explore interconnections in language as used in particular sociopolitical contexts. For Fairclough (2005: 924), discourse is “an element of social processes and social events, and also an element of relatively durable social practice.” CDA is also employed for analytical and theoretical studies of language and society. Fairclough (2005) adopts a tripartite view of discourse: discourse is text in its different varieties (oral, written, and any other semiotic modality), a process (text production and interpretation), and a form of social practice (see also Kang and Hong 2020). Thus, going beyond mere analysis of discourse, CDA scrutinizes the links between discursive and non-discursive elements with a view to a better understanding of societal relationships. In this sense, our research commits to the analysis of discerning social practices (translation) in a specific scenario (volunteering) and to focus on research aiming for social intervention where interpretation and explanation are their main instruments of research by means of a contextualized interpretation and explanation.

Following Kang and Hong (2020), we use Fairclough’s (1992, 1995, 2005) CDA model, considering discourse as an element of social processes, events, and practices; as text production and interpretation; and as meaning acquired through relations with others. Also drawing on Fairclough’s (1992, 1995, 2005) theory of identity construction and societal power relations through discursive positioning, we analyze texts –oral exchanges— inductively drawing on language, interaction as well as attending to the context in which the discourse was produced. In doing so, we explore how volunteer translators’ discursive construction of their identities influences the discursive image of the volunteer translator in society. We also discuss the tensions, power relations, and consequences that shape their social identity. For the purposes of our analysis, we separated volunteer translators’ discourses into two categories: those of translators who continued to provide their services in an NGO at the time of data collection, and those of translators who, for various reasons, had stopped doing so.

Participants and procedure

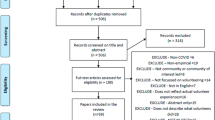

Our sample for this research was composed of 25 volunteer translators and former postgraduate students who had completed the Master in Intercultural Communication and Public Service Translation and Interpretation degree offered by the University of Alcalá, Spain, during the academic years of 2020–2021 and 2021–2022. The main reason for the selection of participants was based on the assumption that, as a preliminary and exploratory study, we decided to focus on a specific group, that is, trained translators. Also, it has to be highlighted that study focus only on translation tasks and no information was collected regarding interpreting.

The call to participate in the study was distributed using an existing electronic mailing list. We used purposeful sampling to generate the sample, which is widely used in qualitative research for the identification and selection of information cases related to the phenomenon of interest (Plainkas et al. 2015). This technique involves identifying and selecting groups of individuals that are especially knowledgeable about a phenomenon of interest (Cresswell and Plano Clark 2011). After obtaining 25 affirmative responses to participate, the responders were informed that the interviews would be completely anonymous, and that they were part of a research project.

The participants had a mean age of 23 years, were predominantly female (75%). Most of them were Spanish (17), although other nationalities took part in the study: France (3), Morocco (2), Uganda (1), and Algeria (2). The different NGOs involved were Salud entre culturas (7 students), Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugido (CEAR) (8 students), Mujeres por África (5 students), Save the Children (3 students) and Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (2 students). The Spanish NGOS —Salud entre culturas, CEAR, and Mujeres por África—are mainly focused on migrant populations. For instance, Salud entre culturas also focuses on migrant health—that is, they offer assistance in terms of translators and interpreters to Spanish hospitals. On the other hand, CEAR promotes the integration of refugees and migrants who need international assistance. Mujeres por África, as stated on its website, contributes to the development of the African continent through the support of its women to promote fair, inclusive, and equitable development in Africa. Save the Children and Médecins Sans Frontières are two international non-profit entities with offices in Spain that also offer assistance to people at risk, including children (Save the Children) and people in dire need of emergency medical aid (Médecins Sans Frontières).

As indicated, our main objective was to focus on discourse elements to determine the identity construction of NGO volunteer translators. It was therefore considered appropriate to establish specific profiles for this purpose. As in other works on CDA and discursive identity (Fahey 2005; Kang and Hong 2020), the semi-structured interview was used as the main data collection instrument. The aim was to gather information on specific aspects of volunteer translator activities in NGOs while ensuring a relaxed atmosphere for the informants. The semi-structured interview, as stated by Cohen, Manion, et al. (2007: 267), allows participants “to discuss their interpretations of the world in which they live, and to express how they regard situations from their point of view.” Considered of the utmost importance to our study in terms of exploring discursive identity was the free exchange of NGO volunteer translators’ opinions and experiences. The interviews, which lasted approximately 35–40 min, were conducted in English and recorded and transcribed for subsequent analysis using QDA Miner Lite software (Provalis Research 2020). This computer-assisted qualitative analysis software generates intuitive coding and organizes coding text segments. For our selection of texts, topic codifications were used, and keywords such as volunteer+translator, community, humanitarian, society or professional. Prior to the interviews, the written consent of the participants was obtained, and they were informed of the purpose of the study.

A script was designed for the semi-structured interviews aimed at collecting information on the individual NGOs, internship duration, translation tasks, and volunteer translator experiences (for example, positive and negative aspects, how the experience influenced day-to-day life, perceptions of translation in the NGO context). Respondents were also asked if they had continued with their volunteer work in the same or another NGO after their internship had ended. If the answer was no, the respondents were asked to state their main reasons for not continuing. If the answer was yes, the respondents were asked to indicate which NGO they continued to volunteer with and how long (months or years) they had been with the NGO, and to explain the reasons for continuing as a volunteer translator in an NGO.

Results and discussion

A CDA of the interview data revealed two main identities in the discourse. For translators who continued as volunteer translators at the time of data collection, the main discursive identity they constructed was social in relation to their experiences of the NGOs nature. For those who no longer worked as volunteer translators at the time of data collection, the main discursive identity they constructed was professional. These identities are discussed individually below.

Discursive construction of a social identity

As pointed out above, volunteering is traditionally associated with good works by citizens who contribute to society altruistically in a form of a new kind of citizenship (López Franco and Shahrokh 2015). Although all our respondents constructed the figure of the volunteer around this idea, they did so in different ways. In the discursive strategies of the informants who continued with their NGO translation work after their postgraduate internship, the social identity of the volunteer was clearly reflected in discourse centered on two axes: (1) the volunteer translator as an agent of change in today’s society, and (2) the volunteer translator as belonging to a community.

As an agent of change in society, the volunteer translator was depicted as a citizen with a mission within society—very much in line with the findings of Kang and Hong (2020)—and with a sense of social responsibility (Fahey 2005) that leads them to tackle social injustices. As shown in Excerpt (1), this was observed in the lexical choices of these respondents, including verbs and expressions such as “vindicate,” “help,” “change society,” and “listen to the voices of the most disadvantaged”:

(1) I believe that translation can vindicate and help regarding the situation in the most disadvantaged countries. I am able to do my bit to help. I have translated texts that will help change society. For example, I have translated documents about different kinds of injustices and child trafficking. I believe that we have to listen to the voices of the most disadvantaged. I feel realized with my work as a volunteer translator for the NGO. (Volunteer 1)

The above excerpt shows that volunteer translation within an NGO was perceived to be an act of helping others and to have consequences for change within society itself (“I believe that translation can vindicate and help …”). The volunteer translator is identified as a spokesperson for minorities (“… the most disadvantaged”), and this was associated with the concepts of responsibility to society and of personal fulfillment (“… to do my bit to help”). Interestingly, this social identity was also perceived to directly affect the personal development of the volunteer (“I feel realized with my work as a volunteer translator …”).

Excerpt (2) further exemplifies the personal development experienced by these volunteer translators:

(2) I have never been so close to the reality lived by migrants than when I interpreted for what they call the “first interview,” which is when the person has to describe their entire journey from start to finish so that a doctor can evaluate the conditions they arrive in. All this touched me greatly and influenced me as a person; it was personal growth that went beyond the fact that I was doing a job as a professional. (Volunteer 2)

Volunteering was thus perceived as enabling the translator to occupy the position of the “good citizen.” In this sense, volunteering was constructed as a helping activity to improve the welfare of others—what other research into the discursive construction of the volunteer has labeled “humanitarian discourse” (Sánchez Ramos 2022; Yap et al. 2011). This social identity of a defender of the disadvantaged who helps overcome linguistic and cultural barriers was seen to empower the volunteer translators and to position them as an agent of change in society.

In relation to the volunteer translator as part of a community, translation was perceived as a collaborative activity that involved commitment to a community in which volunteers, as agents of social change, take on collaborative tasks having direct consequences for the beneficiaries (Kingsberg et al. 2013; Shantz et al. 2014), in what can be considered an exchange of social experiences:

(3) My experience as a volunteer translator has also enabled me to work with other translators with more experience of humanitarian aid, which has made me realize the very important work done by NGOs. Sharing experiences has also helped me a lot. (Volunteer 3)

(4) I felt very supported by the other volunteer translators working on the same project. They really helped me when it came to resolving doubts about specific translation issues. I don’t know, I liked working in a team, whereas other times I’ve preferred individual tasks, but I think that, in a job like this in an NGO, it’s important to be in contact with the other translators. It gives me confidence and makes me feel good. (Volunteer 4)

It can be observed that, in addition to the agent of change and community aspects, the discourse of these respondents very much reflected the social value of translation itself, with volunteers self-characterizing themselves as agents capable of breaking down linguistic and cultural barriers for the benefit of the most disadvantaged. Translation was thus viewed as “an act that brings people together and upholds values of universal access to education, linguistic justice, and equality” (Kang and Hong 2020: 57).

Discursive construction of a professional identity

As shown in Excerpts (5) and (6), a recurring theme in the discursive construction of a professional identity by those respondents no longer volunteering in NGOs was related to the lack of resources, equipment, and training at NGOs:

(5) Immigration, refugees, etc.—this is an inescapable reality and public bodies should invest more to ensure equal rights for all citizens. I think that each hospital, each city should be obliged to provide this service (whether health-related, judicial, administrative, etc.)—provide a service that should not be provided by an NGO. We are doing, yes, a wonderful task, etc., not charity work. We are dealing with a real need that must be met by professionals and whose task should be institutionalized. If there is advanced training, it means that there is a market, right? (Volunteer 4)

(6) I agree that my work helped people and is humanitarian, but the conditions were not right: I had no reference for translating, I was often totally lost, and I felt somewhat undervalued. (Volunteer 5)

The lack of communication seen above between the volunteer translators and their NGOs was also a common theme, along with the need for proper recognition of the work of translators in NGOs. This finding is echoed in studies by Cnaan and Cascio (1999), Bridges Karr (2004), Günter and Wehner (2015), and, more recently, Kartika Dewi et al. (2019).

By positioning themselves as professionals, these volunteers saw translation as an activity that requires specific skills and a high degree of specialization:

(7) I honestly don’t think volunteer translation helps our profession. As a freelance translator, I think that volunteering for an NGO where translation is not considered central should not be allowed. It’s working for free in a job as important as translation, which requires a high degree of specialization. I had to work really hard to get my degree. Translation cannot be passed off as humanitarian aid if we want our profession to achieve the recognition it deserves. (Volunteer 6)

Expressions such as “our profession” or “[being] a freelance translator” come from a position of wanting recognition from society as a translator. Here translation as a profession is seen as being devalued by volunteer work; translation, they maintained, requires proper training and remuneration.

The translators who continued as volunteer translators after their internship saw volunteering as a form of professional empowerment, whereby the volunteer acquires valuable experience. Volunteering gave them strategies for development as professionals, which was linked to social responsibility, which, in turn, produced personal satisfaction and built a social identity. As Excerpts (8)-(10) show, all this converges in such a way that these volunteers felt empowered to effect social change:

(8) My internship experience in an NGO was very fruitful. Thanks to this I discovered in which field I wanted to focus my professional future. This experience influenced me greatly, especially on the emotional level. (Volunteer 7)

(9) Evidently, volunteer translation is one of the best ways to gain work experience in order to be able to enter the professional world. In my case, it helped me get a first impression of the job of a translator, the need to organize myself to complete tasks, the responsibility that comes with translating a text that is going to be published and that can help many people … In addition, for me the personal satisfaction of working in this type of organization is great, as I feel I’m doing my bit. (Volunteer 8)

(10) It was a great experience. I was unaware of the important work that we can do in an NGO, and I translated many different types of texts. It has also helped me to learn the vocabulary and terminology of the NGO and has helped me to translate better because I have been able to practice with texts that were new to me. (Volunteer 9)

In contrast, participants who had ceased volunteering at NGOs rejected a socially orientated identity in favor of a professionally orientated one. This can be observed in their lexical choices, which included “profession,” “intrusion,” and “economic aspect.” These respondents expressed blunt criticism of the unprofessional nature of volunteer translation:

(11) I realized that PSTI [public service translation and interpreting] volunteering greatly affects the profession, since it allows entry to many people without training or knowledge of the code of ethics. And I decided I did not want to be part of that. I think that NGOs and public bodies need to realize that translation and interpreting is a profession like any other and that, as such, it should not be done only on a voluntary basis. (Volunteer 5)

In other cases, as seen in Excerpt (12), despite evaluating their experiences positively, volunteers did not prioritize the social value of the work, instead commenting on how the work of the translator was underappreciated:

(12) Although the experience was generally positive, I did realize that the translator is not highly valued. During my internship, while I was responsible for most of the translations, sometimes other workers translated documents. While they had some knowledge of the two languages, they had not been trained as translators. It is true that the economic aspect is fundamental, but this situation led me to reflect on intrusion and the little importance attached to the profession, despite the fact that our training is exacting. (Volunteer 6)

A comparison of the excerpts in Section 4.1 with the excerpts in this section reveals a discursive tension that has implications for the identity of the volunteer translator in society. Respondents who continued translating as volunteers felt empowered as societal agents of change, while respondents who no longer worked as volunteers felt that the role of the professional translator in society was diminished by volunteering, and that empowerment lay precisely in rejecting such social contributions in favor of recognition of a professional identity. Their professional identity is expressed by positioning volunteer translators as poorly treated and underappreciated amateurs, which aligns with the findings of Fahey (2005). In fact, as Robinson (2015) also suggests, this discursive representation may also indicate that volunteer translations could have a greater critical awareness of their social context.

Conclusion

The volunteer has been a focus of attention in various disciplines, including translation studies. Both quantitative and qualitative studies have investigated aspects such as the motivations of the volunteer translator and the quality of volunteer translation outputs. Although translation can be volunteered in different contexts, it is usually associated with the third sector, and especially with NGOs dealing with the challenge of individuals’ linguistic and cultural integration. This has generated debate about the appropriateness of volunteer translation in terms of its impact on translation as a profession.

In view of the few existing studies on the discursive identities of volunteer translators, we conducted an exploratory qualitative study using the methodology of CDA (Fairclough 1992, 1995, 2005) in order to determine the identity/identities of volunteer translators in the third sector. The three research questions posed in the introduction were answered based on the findings from the 25 semi-structured interviews with former postgraduate students who had completed internships in various NGOs. These results revealed two main discursively constructed identities (RQ1) which were adopted depending on whether they were (1) translators who continued as volunteer translators or (2) those who no longer worked as volunteer translators in an NGO after their initial internship.

These contrasting identities clearly reflect a tension concerning the figure of the volunteer translator in society (RQ2). On the one hand, those who continued as volunteer translators constructed a social identity that characterized them as linguistic and cultural unifiers, facilitators of higher values such as universal education and equality, and reinforcers of moral values, personal identity, and belongingness within a community. On the other hand, those who ceased to volunteer at NGOs believed that volunteer translation threatened both their identity as professionals and their socioeconomic position. This discursive tension reveals the complexity associated with the volunteer translator in society and legitimates the responsibilities of volunteer translators in our society (RQ3).

Our study also has implications for NGOs, with our findings suggesting that NGOs and volunteers need to define their relationships and work reciprocally to improve their effectiveness, as well as improve their communication channels more clearly. It can also be assumed that NGOs may need to reflect upon the way to attract new volunteer translators in order to promote tasks or experiences where the feel like the agents or actors of positive change. By revealing these contrasting identities of volunteer translators, this research adds to our understanding of translation in the NGO context.

Undoubtedly, the results of this preliminary and exploratory study need to be reinforced by analyzing other voices, such as those of NGOs, as this would provide greater insights into the discursive construction of the volunteer translator in the third sector and would potentially permit comparison with other kinds of volunteers. This study, in responding to the demand for research into the volunteer translator and the comparison of discourses, therefore serves as a starting point for further research.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Anastasiou D, Gupta R (2011) Crowdsourcing as human-machine translation (HMT). J Info Sci 20(10):1–15

Ariño Villarroya A, Castelló Cogollos R (2008) El carácter moral del voluntariado. R Esp Sociol.ía 8:25–58

Basalamah S (2020) Ethics of volunteering in translation and interpreting. In: Koskinen K, Pokorn N (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Ethics. Routledge, London, p 227–244

Boéri J, Maier C (eds.) (2010) Compromiso social y traducción/Interpretación. Translation/Interpreting and social activism. ECOS, Traductores e intérpretes por la Solidaridad, Granada

Cámara de la Fuente L (2015) Motivation to collaboration in TED open translation project. Int. Jo Web Based Communities 11(2):210–229. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJWBC.2015.068542

Carreira Martínez O, Pérez Jiménez E (2011) El modelo de crowdsourcing aplicado a la traducción de contenidos en redes sociales: Facebook. In: Calvo Encinas E, Enríquez Aranda M, Jiménez Carra N (eds.) La traductología actual: Nuevas vías de investigación en la disciplina. Comares, Granada, p 99–118

Cnaan RA, Cascio T (1999) Performance and commitment: issues in management of volunteers in human service organizations. J Soc Serv Res 24(3–4):1–37. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v24n03_01

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K (2007) Research methods in education (6th ed.). Routledge, New York

Cresswell JW, Plano Clark VL (2011) Designing and conducting mixed method research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Cronin M (2010) The translation crowd. Tradumàtica 8:1–7. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/tradumatica.100

Deriemaeker J (2014) Th\e power of the crowd: Assessing crowd translation Quality. Dissertation, Ghent University

Désilets A (2007) Translation wikified: how will massive online collaboration impact the world of translation? Retrieved from https://aclanthology.org/2007.tc-1.15.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2023

Desjardins R (2011) Facebook me!: Initial insights in favour of using social networking as a tool for translator training. Ling Antverpiensia 10:175–192. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v10i.283

Desjardins R (2017) Translation and social media: in theory, in training and in professional practice. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Drugan J, Tipton R (2017) Translation, ethics and social responsibility. Translator 23(2):119–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2017.1327008

Fahey C (2005) Volunteers in an organizational setting: a critical discourse analysis of identification and power. Paper presentation at the International Conference on Critical Discourse Analysis, University of Tasmania, Australia

Fairclough N (1992) Discourse and social change. Polity Press, Cambridge

Fairclough N (1995) Critical discourse analysis: the critical study of language. Routledge, New York

Fairclough N (2005) Peripheral vision: discourse analysis in organization studies: the case for critical realism. Org Stud 26(6):915–939. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605054610

Foucault M (1980) Power/knowledge: selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977. Phanteon Books, New York

Foucault M (1991) Politics and the study of discourse. In: Burchall G, Gordon C, Miller P (eds.) The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Friedrich J (2019) Your presence is enough to make a huge difference’: constructions of agency in voluntourism discourse. Elphinstone Rev 5:2–21

Gough J (2011) An empirical study of professional translators’ attitudes, use and awareness of Web 2.0 technologies, and implications for the adoption of emerging technologies and trends. Lingu Antverpiensia 10:195–217. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v10i.284

Grönlund H (2011) Identity and volunteering intertwined: reflections on the values of young adults. Voluntas 22:852–874. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-011-9184-6

Günter ST, Wehner T (2015) The impact of self-determined motivation on volunteer role identities: a cross-lagged panel study. Perso Individ Diff 78:14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.01.017

Jiménez-Crespo MA (2017) Crowdsourcing and online collaborative translations: expanding the limits of translation studies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Jones P (2019) Motivation of volunteer translators in the online game popmundo. Dissertation, University of Tampere

Kang JH, Hong JW (2020) Volunteer translators as ‘committed individuals’ or ‘providers of free labor’? The discursive construction of ‘volunteer translators’ in a commercial online learning platform translation controversy. Meta Translator J 65(1):51–72. https://doi.org/10.7202/1073636ar

Karr LB (2004) Keeping an eye on the goal(s): a framing approach to understanding volunteers’ motivations. V Inzet Onderz 1(1):55–62

Kartika Dewi M, Manochin M, Belal A (2019) Marching with the volunteers: their role and impact on beneficiary accountability in an Indonesian NGO. Acc Auditing Account J 32(4):11l7–1145. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-10-2016-2727

Kingsberg S, Tolsma J, Ruiter S (2013) Bringing the beneficiary closer: explanations for volunteering time in Dutch private development initiatives. Non Voluntary Sect Qu 42(1):59–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011431610

Läubli S, Orrego-Carmona D (2017) When Google translate is better than some human colleagues, those people are no longer colleagues. In: Esteves-Ferreira J, Macan J, Mitkov R, Stefanov OM (eds.) Translating and the Computer 39. AsLing, London, p 59–69

López Franco E, Shahrokh T (2015) The changing tides of volunteering in development: discourse, knowledge and practice. IDS Bull. 46(5):17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-5436.12172

McDonough Dolmaya J (2012) Analyzing the crowdsourcing model and its impact on public perceptions of translation. Translator 18(2):167–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799507

Moulaert F, Mehmood A, MacCallum D, Leubolt B (2017) Social innovation as a trigger for transformations: the role of research. European Commission

O’Hagan M (2011) Introduction: community translation: translation as a social activity and its possible consequences in the advent of Web 2.0 and beyond. Lingu Antverpiensia 10:1–10. https://doi.org/10.52034/lanstts.v10i.275

Olohan M (2014) Why do you translate? Motivation to volunteer and TED translation. Transl. Stud. 7(1):17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2013.781952

Plainkas LA et al. (2015) Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 42(5):533–544

Pérez-González L, Susam-Saraeva S (2012) Non-professionals translating and interpreting: participatory and engaged perspectives. Translator 18:149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2012.10799506

Perrino S (2009) User-generated translation: the future of translation in a Web 2.0 environment. J. Specialised Translation 12:55–78

Provalis Research (2020) QDA miner lite. https://provalisresearch.com/es/products/software-de-analisis-cualitativo/freeware/ Accessed 10 Jan 2024

Pym A (2011) Translation research terms: a tentative glossary for moments of perplexity and dispute. In: Pym A (ed.) Translation Research Projects 3. Intercultural Studies Group, Tarragona, p 1–32

Ray R, Kelly N (2011) Reaching New Markets through Transcreation. Common Sense Advisory. https://www.novilinguists.com/sites/default/files/Common%20Sense%20Advisory%20-%20Reaching%20New%20Markets%20through%20Transcreation.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2024

Robinson D (2015) Local heroes? A critical disocourse analysis of the motivations and ideologies underpinning community-based volunteering. Dissertation, University of Birnmingham

Sánchez Ramos MM (2019) Mapping new translation practices into translation training: promoting collaboration through community-based localization platforms. Babel Int J Transl 65(5):615–632. https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.00114.san

Sánchez Ramos MM (2021) Análisis de la traducción social en línea: estudio basado en una metodología mixta. Hermēneus. Rev Traducción e Interpretación 23:391–420. https://doi.org/10.24197/her.23.2021.391-420

Sánchez Ramos MM (2022) Constructing identities in crisis situations: a study of the ‘volunteer’ in the Spanish and English press. In: Chiluwa IE (ed.) Discourse, media, and conflict: examining war and resolution in the news. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 324–339

Shantz A, Saksida T, Alfes K (2014) Dedicating time to volunteering: values, engagement, and commitment to beneficiaries. Appl Psychol. 11(1):25–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12010

Snyder M, Omoto AM (2008) Volunteerism: social issues perspectives and social policy implications. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2(1):1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2008.00009.x

Tesseur W (2019) Communication is aid -but only if delivered in the right language: an interview with translators without borders on its work in danger zones. J War Cult Stud 12(3):285–294

Tziafa E (2019) The role and impact of volunteer translation in translators’ training. Méthodal OpenLab, 3. https://methodal.net/The-role-and-impact-of-volunteer-translation-in-translators-training-240. Accessed 10 Jan 2024

Yap SY, Byrne A, Davidson S (2011) From refugee to good citizen: a discourse analysis of volunteering. J Refugee Stud 24(1):157–170. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feq036

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out within the framework of the following projects “Original, translated, and interpreted representations of the refugee cris(e)s: methodological triangulation within corpus-based discourse studies” (PID2019-108866RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and “Multidimensional analysis of machine translation in the third sector (PIUAH23/AH-11), funded by University of Alcalá, Madrid, Spain).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This research is entirely by María del Mar Sánchez Ramos, University of Alcalá (Madrid, Spain).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of University of Alcalá (Madrid, Spain). The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

The participants were informed about the research ethics before conducting interviews. They were assured that their participation would remain anonymous in the study and that their privacy would be protected. Written consent was obtained from study participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sánchez Ramos, M.d.M. Volunteer translators in non-governmental organizations: exploring their identity and power through discourse analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 581 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03103-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03103-4